War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was the federal agency created in 1942 to care for the 110,000 Japanese Americans whom the army removed from the West Coast during World War II. Under the leadership of directors Milton Eisenhower (briefly) and Dillon S. Myer , the WRA built and operated a network of camps in the interior, where those removed were subjected to involuntary confinement. As part of the agency's mission to resettle Japanese Americans outside of the West Coast excluded zone, WRA officials implemented a controversial "loyalty program" that led to segregation and harsh treatment of those inmates deemed "disloyal," even as they took up the defense of those adjudged "loyal" and assisted them to find jobs and housing outside the camps. The legacy of the WRA, and the opinion of both former inmates and historians as to the agency, remains mixed and evolving.

Origins and Organization

The War Relocation Authority was created in the wake of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's issuing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The Order granted the army the authority to create a military zone and to remove all residents of Japanese ancestry. The President and his advisors agreed that a civilian agency should be created to care for the excluded population. The WRA was given official life on March 18, 1942, by Executive Order 9102.

President Roosevelt meanwhile adopted Bureau of the Budget Director Harold Smith's suggestion that Milton S. Eisenhower, brother of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, be transferred from the Agriculture Department to head the new agency. [1] Though Eisenhower's tenure as WRA Director would last only three months, many key decisions were made on his watch that shaped the WRA over the course of its history. Eisenhower began by setting up a regional office in San Francisco and recruiting staff from other federal agencies. He made a verbal deal with John Collier, director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to establish a camp at the Colorado River reservation under BIA management as a model community. He set up a Japanese American "advisory council" headed by Mike Masaoka , establishing what would remain a close relationship between the WRA and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). He approved leave programs whereby Nisei college students could leave confinement and continue their studies outside the West Coast. (See National Japanese American Student Relocation Council .) Eisenhower and his associates also began developing a set of policies regarding public relations. Most notably, in parallel with the army's Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), staffers prepared guidelines for use of euphemistic terminology. Staff members were required to refer to inmates as "evacuees" and to the facilities they planned to create as "relocation centers" or "relocation projects" rather than "internment centers" or "concentration camps" or even "camps" of any kind. [2]

Eisenhower originally envisioned as least a certain amount of voluntary departures by Japanese Americans and of planned resettlement in outside communities. However, such a position soon proved problematic. On March 27, following complaints from inland communities about entry of "dangerous" Japanese Americans, the army's West Coast Defense Command barred further " voluntary evacuation ." Three days later, the WCCA began transporting Japanese Americans to a network of holding centers, dubbed " assembly centers " in officialese, located in hastily-adapted racetracks or fairgrounds within the exclusion areas. As a result, the Japanese Americans were already incarcerated by the time the WRA could take custody of them. Finally, in the wake of a disastrous meeting on April 7, 1942, with western state officials, who flatly refused to accept Japanese American migrants except in custody, Eisenhower reluctantly determined that mass confinement was the only foreseeable means of proceeding. Therefore, Eisenhower established plans for the building of a network of American-style concentration camps. When Eisenhower resigned in June 1942, President Roosevelt chose Eisenhower's former Department of Agriculture colleague Dillon Myer to take his place. Myer would lead the WRA for the rest of its life.

Planning the Camps

Even before Eisenhower's departure, the new WRA had started the planning and construction of long-term camps for Japanese Americans. As it confined Japanese Americans in "assembly centers," the WCCA also identified two sites—what would become Manzanar and Poston —and began building longer-term camps on them, which it announced it would turn over to the WRA. The WRA meanwhile considered 300 more potential sites, ideally on large tracts of federally owned land with sufficient water supplies, a reasonable distance from any strategic area. [3] In addition to Manzanar and Poston, WRA officials eventually settled on eight sites: Tule Lake , California; Minidoka , Idaho; Gila River , Arizona; Topaz , Utah; Heart Mountain , Wyoming, Amache , Colorado; and Jerome and Rohwer , Arkansas. The camps were built from scratch, with barbed wire fences around the perimeter and guard towers overlooking them. Wooden barracks with tar-paper walls, with one 20"x20" room to a family, were designated as housing. Separate—and much nicer—quarters were built for administrative personnel and guards. Other buildings prepared for use were dining halls and bathroom/laundry facilities. (Libraries and school buildings were not initially included in camp plans, but it quickly became obvious that they would be needed, and eventually a large share of WRA budgets would be devoted to educational expenses). Unrealistic building schedules and wartime shortages of labor and materials led to the camps being incomplete when the first inmates began to arrive. Indeed, much of Manzanar was constructed with the aid of volunteer Japanese American labor teams who undertook the construction out of patriotic duty.

Meanwhile, the WRA worked to store all personal property for the inmates. Amid widespread loss and despoliation of the goods of Japanese Americans at the time of removal, the army had secured warehouses to store property. However, these warehouses were not bonded or guarded, and the goods stored within suffered vandalism and theft. In August 1942, the WRA established the Division of Evacuee Property, and assumed responsibility for supervising the storage of the remaining property.

Policies and Procedures

Over the spring and summer of 1942, WRA officials developed their policies and procedures. [4] The WRA attempted to set up functioning communities behind barbed wire, establishing educational programs, recreation facilities, newspapers , and other elements of community life. The government would supply inmates with basic food, housing, medical care , heating stoves and electricity, and would offer them a clothing allowance. In order to streamline orders for food for the inmates, the WRA was granted permission to use the Army Quartermaster service, but maintained civilian rationing controls. To save money and defend against charges that the inmates were being "coddled," daily food costs were limited to a maximum of $.50 per inmate. As a result of such chintzy budgets, plus inexperienced inmate cooks, the food was poor in both quality and nutrition, at least until the inmates could produce their own. Meanwhile, both to spread budgets and to encourage self-reliance among those confined, WRA officials employed inmates to perform most tasks in the camps. Employees were paid a flat rate of $14 per month for ordinary workers, capped at $19 per month for doctors and dentists, a scale deliberately set lower than the minimum pay for American GIs. Importantly, the WRA banned private enterprise in the camps and sponsored the formation of cooperative enterprises among inmates to provide additional services. The cooperatives opened stores where inmates could purchase food and supplies, and also ran such other facilities as barbershops and shoe repair shops. [5]

Meanwhile, WRA officials developed center regulations. On the one hand, compared to the WCCA, these were considerably less invasive. Inmates enjoyed the right of free assembly, and were not restricted in their use of the Japanese language in camp. Furthermore, inmates were detailed to police themselves inside camp—soldiers were not called in except in case of emergencies—and were free from arbitrary searches of their barracks. Unlike in the assembly centers, there was no prior restraint by official censors on camp publications. However, the essential liberties of Japanese Americans remained restricted. They required a pass to enter or leave camp; some visiting Nisei soldiers subsequently had to sneak in and out in order to visit their families. Armed sentries in guard towers patrolled the perimeter fences, and shot at inmates who came too close. In two well-documented cases, inmates were shot and killed by perimeter guards. The inmates also were initially denied permission to use cameras or shortwave radios. Both the center regulations established at WRA headquarters in Washington and their enforcement at the various camps were gradually relaxed over time.

Paternalism and Americanization

Whether they were inspired by hostility to inmates or sympathy for their plight, WRA officials from Director Dillon Myer downward agreed that the prewar concentration of Japanese Americans in West Coast ethnic communities and the vestiges of Japanese culture were part of the problem that led to their exclusion, and they sought to address it by a policy of forced "Americanization" within camp, with the stated goal of preparing the inmates for their dispersal into mainstream American life afterwards. [6] The WRA emphasized dissemination of American values through patriotic exercises, sponsoring of Boy Scout troops, and organization of English and citizenship classes for Issei (even though they remained barred from naturalization). [7]

As a symbol of American ways at work, the WRA established "self-government" inside the camps, with elected [8] and cooperative boards exerting authority over inmates, running schools and hospitals, and preserving internal order. Yet WRA Community Analysis Section head John Embree compared camp self-government to that of a high school in that "It is pseudo-democratic and all the important decisions are pushed through by administration people." [9] Both because of official mistrust of "enemy aliens" and because WRA officials sought to inculcate democratic sentiment among American citizens, elected positions in camp "self-government" were initially restricted to Nisei. These policies not only contributed to largely held views of such government as a "sham" but were a leading factor in stoking discontent among Issei and exacerbating existing tensions between loyalist and anti-administration factions among inmates. These tensions exploded into the Poston strike and Manzanar riot/uprising in November and December of 1942 respectively.

Throughout its life the agency came under heavy fire from West Coast and conservative congressmen and tabloids for "coddling" the inmates. [10] Two congressional investigations of the WRA followed the Manzanar riot, the first in January 1943, led by Senator Albert B. Chandler of Kentucky, the second by the House Un-American Activities Committee . (Dies Committee) in June1943. The outside criticism led the agency into a defensive crouch, which led administrators to adopt "policies which showed that their fear of adverse publicity had overcome any humanitarian impulse." [11]

Preparing for Resettlement

Concerned that Japanese Americans, once confined by the government, would lose their self-respect and become economically dependent on government charity (as Native Americans were perceived as doing), Dillon Myer insisted that the agency envision its mission as temporary wartime custody: the camps were not to be designed or run as permanent facilities. Instead, the inmates were to be prepared to resettle in mainstream society afterwards. Even as inmates were encouraged to take paid work inside camp at the miserable salaries offered—which did offer them essential experience for the postwar era—WRA officials debated the process of resettling inmates outside the camps. Even before the WRA took custody of the inmates, the NJASRC had been organized to assist students in transferring to outside colleges. Meanwhile, the WCCA had begun the practice of offering temporary "furloughs" to inmates to perform agricultural work under "supervision." (In October 1942 some 10,000 inmates would be recruited for emergency labor harvesting sugar beets in Rocky Mountain states). Beginning in July 1942, WRA staffers devised a cumbersome system of "leave permits" that resulted in only 11 applications being processed in the 10 weeks that followed. [12] A somewhat more flexible process followed in October 1942. The inmate requesting release, however, still had to find a sponsor—and also prove there was no strong community opposition to such resettlement—then pass an FBI check. The WRA reserved the right to return any paroled inmate—a requirement that was both unenforceable as well as unconstitutional, as WRA Solicitor General Philip Glick privately recognized. [13]

In the meantime, together with the JACL, Dillon Myer was among those who sought Nisei eligibility for military service, seeing this as a crucial step in reintegrating Japanese Americans into mainstream society after the war. In early 1943, such lobbying efforts were rewarded with the formation of the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team . The WRA maintained pressure for the phased resumption of the military draft for Nisei, which occurred in January 1944. When the draft resister movement sprang up in response, with Nisei refusing to enlist until their civil rights were restored, the WRA and the JACL supported their prosecution and exemplary punishment.

Loyalty Questionnaire and Segregation

Once the War Department announced in February 1943 that Nisei would be permitted to enlist, the WRA moved to associate itself and its resettlement efforts with the military. The army created a Joint Board to verify the "loyalty" of Nisei recruits, using the recruit's responses to a hastily-drafted " loyalty questionnaire ," information drawn from military intelligence reports and FBI files, plus endorsements from outside supporters. The WRA obtained War Department assent to have the Joint Board examine the “loyalty” of each adult inmate. The result was a sadly flawed process that caused untold stress among inmates and divided many families. First, instead of examining overt acts and their impact on security, the WRA sought instead to judge the amorphous concept of "loyalty," with the Joint Board relying heavily on guilt by association. Worse, the questionnaire, adopted wholesale from that of the War Department, was hastily drafted and not well adapted for cases other than military recruits. Made up of largely irrelevant questions, two were particularly suspect: Question 27, which asked "Are you willing to serve in the Armed Forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?," while question 28, pressed inmates to "swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America...and foreswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization."" The Nisei resented having to swear unconditional loyalty to the country that had imprisoned them, and they worried that agreeing to "foreswear" other allegiance constituted an admission that they had such allegiance. For the Issei, who were barred from American citizenship, Question 28 violated international law by obliging them to renounce their Japanese citizenship. (the WRA ultimately changed the wording to require Issei to "abide by" American law).

Meanwhile, the WRA had not accounted for the negative impact of a year of confinement without charge on the morale and patriotism of those affected. When the loyalty questionnaire was suddenly sprung on them, without sufficient notice or guidance, and with no assurances as to how the information they offered would be used, the inmates were understandably suspicious and resentful. While many Japanese Americans, especially middle-aged Issei who had lost the balance of their property during the initial removal, had no interest in resettling outside, the WRA coerced each inmate to fill the forms out and deemed those who refused automatically disloyal. Still, the vast majority of inmates responded positively to the two questions. However, some 15% of the total refused to fill out the form or made "wrong" answers to Questions 27 or 28 , including disproportionate numbers of military-age Nisei men who refused to enlist. Whether motivated by protest, confusion, disillusionment or (most often) desire to keep families together, these so-called " no-nos " were stigmatized as "disloyals" and barred from resettlement.

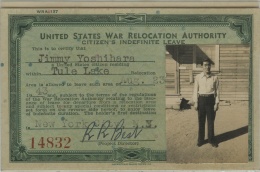

Although WRA officials assumed that once the loyalty tests were completed, all inmates adjudged "loyal" would rapidly be resettled, the War Department (for its own reasons) and various WRA critics called for the "disloyals" to be segregated out, and deported after the end of the war. Under protest, Myer agreed to the "segregation." He selected the Tule Lake camp as the segregation center , and some 12,000 "disloyals" were transferred over the following months. [14] Many existing Tule Lake inmates refused to move, and the result was overcrowded and bleak conditions. The "segregees" were treated as enemies by the Tule Lake administration, and there were numerous cases of beatings of inmates by guards and imprisonment in stockades.

On September 14, 1943, the White House presented Congress with a report on Japanese Americans, part of a deal to shut down the Congressional inquiries on the WRA. In his transmittal letter, President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that with the successful completion of segregation, the WRA could now redouble its resettlement efforts. In particular, Roosevelt promised that the Japanese Americans could return to the West Coast "as soon as the military situation will make such restoration feasible." [15]

However, it was not to be. In November 1943 Tule Lake inmates organized a strike, and there was a minor incident of violence. The administration invited army troops in to restore order, and the camp remained under martial law through January 1944. Distorted West Coast newspaper reports of the "Tule Lake" riot served to embitter public opinion against all Japanese Americans, thereby blocking (as intended) the reopening of the excluded zone even to those inmates adjudged "loyal," and further stalling their resettlement. By the end of 1943, only some 17,000 inmates, less than 15% of the total, had left camp.

After the Tule Lake incident, President Roosevelt and his advisors agreed that the WRA required transfer to an existing Cabinet department, ostensibly for administrative efficiency but in fact primarily for political cover. After significant debate, in February 1944 the WRA was placed within the Interior Department, under the jurisdiction of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes , who proved an outspoken public defender of the rights of Japanese Americans. [16] Resettlement, however, remained blocked—President Roosevelt refused to authorize the opening of the West Coast until after the November 1944 election. Despite all the strenuous efforts of the WRA to encourage relocation outside the excluded zone, only about 17,000 inmates resettled in 1944. [17]

Encouraging Resettlement

During 1943-1944, the WRA's mission gradually shifted from constructing and managing camps to the opening of regional resettlement offices and assisting Japanese Americans to leave camp. WRA officials recruited sponsors who would provide Nisei with jobs or education, and helped migrants find housing. WRA staffers organized social service agencies to assist resettlers and advocated for them against discrimination. [18]

WRA officials took for granted the desirability of dispersing ethnic Japanese throughout the United States, and facilitating their absorption into the larger population. [19] Even once the ban on return to the West Coast was lifted in early 1945, the WRA continued to use both financial assistance and moral suasion to push inmates to resettle outside. Myer, despite his increasingly public opposition to removal, actually claimed that nationwide resettlement made confinement a boon to the inmates. "The Nisei, over the long pull, are better off as a result of the evacuation because of their dispersion over the country and the better understanding that the country as a whole has of their problem and of the problems on the West Coast." [20]

In support of this mission, WRA administrators teamed up with staffers from the Office of War Information to produce favorable propaganda, including such pamphlets as "Nisei in Uniform" and "Myths and Facts about Japanese Americans." First lady Eleanor Roosevelt , who had toured the Gila River camp in Dillon Myer's company in April 1943, contributed a laudatory article in Collier's magazine. [21] Former U.S. ambassador to Japan Joseph Grew and Nisei war hero Ben Kuroki were dispatched on speaking tours, while famed photographer Ansel Adams was invited to Manzanar, where he photographed smiling and industrious "loyal" inmates. A team of photographers, including Nisei artist Hikaru Iwasaki , was engaged by the WRA in 1944-1945 to document in photographs the successful new lives of resettlers. WRA administrators required inmates, as a condition of release, to attend officially-sponsored seminars on topics such as "How to Make Friends" and "How to Behave in the Outside World," and to pledge not to congregate with other Japanese Americans in their new homes in order to promote their "assimilation." [22]

Defending WRA and Closing

On January 2, 1945, the army lifted the West Coast exclusion. As the camps opened up, the inmates began departing at an accelerated pace. In mid-January 1945 the WRA announced that it would close all camps other than Tule Lake (Jerome having already closed in mid 1944) by the end of the year. The decision sparked a storm of protest among inmates and their supporters. Fair Play and religious groups that had long supported Japanese Americans (and called for the closing of the camps) now begged the WRA to reconsider its decision. [23] The WRA's policy prompted inmates from the different camps to call an emergency All Center Conference , which met in Salt Lake City from February 18-24th, 1945. They drew up a petition and a list of 21 detailed recommendations for the WRA to help ease the transition out of the camps. Dillon Myer responded to all suggestions by insisting that the rapid winding up of the camps was imperative, and that the care and reestablishment of the Japanese Americans remained primarily a responsibility of local welfare agencies. [24]

Instead, as 1945 went on, the WRA gradually cut off all but the most essential services within the camps. After the surrender of Japan and the end of the war in early September, WRA officials pressed the last inmates to depart, and at the end of the year finally resorted to rounding up the few remaining inmates and transporting them forcibly back to their original points of departure. At Tule Lake, where inmates remained confined through the end of the war, a process of emptying began afterwards, until the high-security camp closed its doors in March 1946. [25] On June 26, 1946, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9742 officially terminating the WRA. A successor agency, the War Agency Liquidation Unit, put together a useful study of resettlement. [26]

Legacy

Over its life the WRA spent over $160 million, oversaw over $100 million in government property, and employed 3,000 people in the camps and in the agency's various offices. [27] Its operations were sufficiently complex and controversial, and the historical picture of the agency so mixed, that it is difficult to speak about it in balanced fashion. During the WRA's lifetime, its operations were most frequently criticized by conservatives, many of them with a political self-interest in attacking the Roosevelt administration or an axe to grind against Japanese Americans, as an example of "New Dealish" bureaucracy and government waste or for "coddling" dangerous Japanese. While a few Nisei activists and ACLU lawyers challenged the WRA's arbitrary treatment of dissidents at Leupp and the "no-nos" at Tule Lake, or supported the draft resisters, many Japanese Americans saw the agency as their chief supporter against the bigots. In 1946, the JACL honored Dillon Myer at a banquet as a stalwart champion of human rights. Even a generation later, one book reported, "Most evacuees in retrospect, and many while they were in camps, have given the WRA credit for an enlightened attitude." [28] However, beginning in the 1970s, in conjunction with the movement for Japanese American redress , activists such as Raymond Okamura and Gary Y. Okihiro offered more critical perspectives on WRA paternalism and the ideology of resettlement, while Michi Nishiura Weglyn underlined the injustice of the "segregation" policy. [29] The new critique reached a climax at the end of the redress period with Richard Drinnon's powerful, vengeful broadside against Dillon Myer as the deceitful and racist "Keeper of Concentration Camps" who sought to eradicate ethnic Japanese communities. [30] In the 21st century, various scholars have attempted to offer a more rounded view of the WRA, taking account of both the circumstances and the intellectual climate of the times. It might be argued that the image of the War Relocation Authority they present is both more positive in many respects and more negative in others than previous accounts. [31]

Footnotes

- ↑ Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2001), 128-30.

- ↑ Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008), 69. Inmates at Poston were labeled "residents" and those at Tule Lake "colonists."

- ↑ The requirement for public land was ultimately stretched in case of the Arizona facilities to include Native American reservations—despite opposition from local Indians—while other camp sites were built on land that was a hodgepodge of public land owned by different jurisdictions, plus small amounts of privately-owned land purchased by the government.

- ↑ In view of the input that Dillon Myer and the WRA received from Mike Masaoka and the JACL, WRA critic Richard Drinnon, using considerable exaggeration, refers to the relationship between Myer and Masaoka as "symbiotic" (72) and leading to a "WRA-JACL line" (124) in his book Keeper of Concentration Camps (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

- ↑ John Howard, Concentration Camps on the Home Front (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- ↑ To be sure, the WRA did not altogether ban expression of Japanese culture in camp. Rather, with the WRA's blessing or tacit permission, older inmates—especially Issei women unaccustomed to having time on their hands—occupied themselves by engaging in Japanese arts and crafts such as ikebana, Japanese woodworking, dance, and furniture making, and they took the opportunity to instruct Nisei youngsters in such arts and crafts.

- ↑ John Howard argues convincingly that camp administrators granted Christian religious missionaries a privileged position. However, the extent to which the WRA colluded in missionary efforts to convert Buddhists or unconstitutionally favored Christian religious practice is unclear. Howard, Concentration Camps on the Home Front .

- ↑ Community councils

- ↑ Cited in Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories , 67.

- ↑ Kevin Allen Leonard, The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006), 123.

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (1982. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 163.

- ↑ WRA: A Story of Human Conservation , 36, 38-40.

- ↑ Philip Glick, letter to Maurice Walk, October 1, 1942. Series 19 correspondence file, WRA papers, RG 210, NARA.

- ↑ Also sent to Tule Lake were a group of dissident inmates arrested after the "Manzanar riot" and arbitrarily confined at a former Indian school at Leupp , Arizona.

- ↑ U.S. Senate, 78th Congress, First Session, Document Number 96, "Message From the President of the United States Transmitting Report on Senate Resolution No. 166 Relating to Segregation of Loyal and Disloyal Japanese in Relocation Centers and Plans for Future Operations of Such Centers," September 14, 1943, 2.

- ↑ In mid-1944, after the WRA was placed within the Department of the Interior, the agency was also assigned to run the emergency shelter at Fort Orange in New York where 1000 refugees, predominantly Jewish, had been offered temporary humanitarian refuge.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The WRA's strong efforts in these fields led historian Kevin Leonard to compare the agency's role to that of the Freeman's Bureau in supporting African-Americans during Reconstruction Kevin Allen Leonard, "Years of Hope, Days of Fear: The Impact of World War II on Race Relations in Los Angeles," Ph.D. diss., University of California, Davis, 1992, chapter 5.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, "Birth of a Citizen: Miné Okubo and the Politics of Symbolism" in Robinson and Elena Tajima Creef, eds. Miné Okubo: Following Her Own Road (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), 154.

- ↑ Letter, Dillon Myer to Carey McWilliams, March 7, 1946. Japanese-American Files, Box 4, Carey McWilliams Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ↑ Eleanor Roosevelt, "A Challenge to American Sportsmanship," Collier's 112 (16 October 1943): 21, 71.

- ↑ Miné Okubo, Citizen 13660 (Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1983) (1946), 207.

- ↑ See, for example, Leonard Bloom, "Fair Play For the Nisei," The Nation , November 17, 1945, 521-2.

- ↑ Letter, [Masaru Narahara] All Center Conference to Dillon Myer, June 18, 1945, attached to letter, Masaru Narahara to Roger Baldwin, July 18, 1945, Japanese American files 1945, Reel 230, American Civil Liberties Union Papers, 1917-1950, Princeton University Library (copy in Library of Congress).

- ↑ Greg Robinson, A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 255.

- ↑ United States Department of the Interior, War Agency Liquidation Unit, People in Motion: The Postwar Adjustment of the Evacuated Japanese Americans (Washington DC), GPO, 1947.

- ↑ Drinnon, 8–9; Greg Robinson, By Order of the President , 2.

- ↑ Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans During World War II (New York: Macmillan, 1969), 237.

- ↑ See, for example, Raymond Okamura, "'The Great White Father': Dillon Myer and Internal Colonialism," Amerasia Journal 13:2 (1986—87): 155—60; Gary Y. Okihiro, "Japanese Resistance in America's Concentration Camps: A Re-evaluation," Amerasia Journal 2 (Fall 1973): 20–34; Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996) (1976).

- ↑ Drinnon, Keeper of Concentration Camps , Ibid.

- ↑ Some of the important studies are Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004); John Howard, Concentration Camps ; Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition ; Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories ; and Greg Robinson, A Tragedy of Democracy .

Last updated Dec. 15, 2023, 5:34 p.m..

Media

Media