Farewell to Manzanar (book)

| Title | Farewell to Manzanar: A True Story of Japanese American Experience during and after the World War II Internment |

|---|---|

| Author | Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston; James D. Houston |

| Original Publisher | Houghton Mifflin Company |

| Original Publication Date | 1973 |

| Current Publisher | Houghton Mifflin Company |

| Current Publication Date | 2002 |

| Pages | 188 |

| WorldCat Link | https://www.worldcat.org/title/farewell-to-manzanar/oclc/967072359/ |

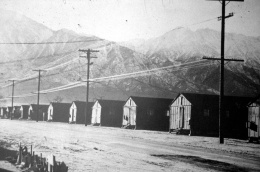

Popular memoir that tells the story of one family's forced removal and confinement at Manzanar through the eyes of a young girl. First published in 1973, Farewell to Manzanar has sold over one million copies and is one of the most widely read accounts of Japanese American incarceration and its aftermath.

Synopsis

Written in the first-person voice of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Farewell to Manzanar is divided into three parts. Part I includes eleven chapters that begins with the attack on Pearl Harbor and follows the Wakatsuki family—Jeanne is the youngest of ten children—from their Ocean Park, California, home to Terminal Island , where they move to after Ko, Jeanne's father, is arrested, and on to Manzanar. Jeanne describes the difficult early conditions at Manzanar—the dust storms, the poor food, and difficult and crowded housing conditions—and the turmoil in the camp in the form of the December 1942 riot/uprising and the " loyalty questionnaire " episode of early 1943. Chapters are also devoted to her father's (and to a lesser extent her mother's) prewar life and her father's interrogation while he is interned at the Ft. Lincoln, North Dakota detention camp.

Part 2 includes ten chapters and covers the normalization of life at Manzanar, the closing of the camps and the family's return to California, Jeanne's middle school and high school years as she struggles to put the past behind her. At Manzanar, the Wakatsukis engage in a wide range of activities from her father taking up wood carving and gardening, to a brother playing in the Jive Bombers swing band, to others playing various sports. As security loosens as the war progresses, inmates are allowed to camp and explore beyond the fences. Eventually, several of her siblings leave for cannery jobs in Seabrook Farms, New Jersey . The younger siblings return with their parents to California, eventually living in a housing project in Long Beach. While her mother works in a fish cannery, her father struggles to reestablish himself. Meanwhile Jeanne gains a level of acceptance in school in Long Beach and later in San José. One chapter is devoted to a 1946 visit by her brother Woody to visit relatives in Japan as an American soldier in the Military Intelligence Service .

Part 3 includes a single chapter that sees Jeanne return to the Manzanar site some thirty years later with her husband and three children, eventually finding the site of her old barracks room. There, she recalls past experiences at the camp, including her father's last defiant car ride through the camp.

Background and Legacy

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston (1934– ) and James D. Houston (1933–2009) were a husband-and-wife team who collaborated on the writing of the book based on Jeanne's childhood experiences. They met as journalism students at San Jose State College in the 1950s and married soon after graduating. Jeanne had been born in Inglewood, California, but mostly grew up before the war in Ocean Park, a seaside community from which her father worked as a commercial fisherman. After the incarceration, the family lived in a Long Beach housing project, then moved to San Jose where her father farmed. Jim was born in San Francisco and grew up there, graduating from Lowell High School. Married in 1957 in Hawai'i, the Houstons spent three years in Great Britain where Jim was stationed while in the Air Force. It was there that he began writing and published his first novel in 1968 based on his experiences there. In 1961, they moved back to California, first to Palo Alto, where Jim attended graduate school at Stanford, then settling in Santa Cruz where they raised their three children. Jim became well known as a writer of novels and non-fiction work and as an editor and writing teacher, his works mostly delving into aspects of California's—and to some extent Hawai'i's—multicultural history. After Farewell , Jeanne reignited her interest in writing, working on screenplays, non-fiction, and a novel, The Legend of Fire Horse Woman , based on the life of an Issei picture bride at Manzanar.

Jeanne traces the origins of the book to an incident in about 1971 when a nephew—the one whose birth at Manzanar is noted in the book—came to interview her. A student at UC Berkeley, he was studying the wartime incarceration in a class and came to her because his own parents would not talk about it. Houston at first gave superficial answers to his questions until he "looked at me very strangely and then he said Auntie, how did you feel about that? For the first time, I stopped and allowed myself to feel about it, and it was devastating." This was also the first time that her husband heard more than superficial stories of her family's incarceration as well. Thinking that there might be a book in this story, Jeanne began telling her story into a tape recorder. The book evolved from something they thought would be just for the family, especially the thirty-six Wakatsuki nieces and nephews, into a book published by a mainstream publisher. In a later essay Houston wrote that her life changed after the book was published: "The year spent delving into those three years of my childhood and its aftermath was as powerfully therapeutic as years with a psychiatrist. I reclaimed pride in my heritage. I rediscovered my ability to write." [1]

Mainstream reviews were uniformly positive. Though not necessarily geared towards children, teachers and school librarians embraced the book, and it became required reading in many public schools subsequently and likely "the best-known children's book about the internment," according to historian Greg Robinson. It also was adapted into a landmark made-for-television movie in 1976. It was reissued with a new afterword in 2002. It has gone to sell over one million copies. [2]

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

Might also like

The Little Exile

by Jeanette S. Arakawa;

Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp

by Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey;

Manzanar to Mount Whitney: The Life and Times of a Lost Hiker

by Hank Umemoto.

For More Information

Houston, Jeanne Wakatsuki, James D. Houston, and Anthony Friedson. "No More Farewells: An Interview with Jeanne and James Houston." Biography 7.1 (1984): 50-73.

Kim, Elaine H. Asian American Literature: An Introduction to the Writings and their Social Context . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982.

Yamamoto, Traise. Masking Selves, Making Subjects: Japanese American Women, Identity and the Body . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Reviews

Kirkus Reviews , Oct. 18, 1973. ["Mrs. Houston survived to write this sad memoir of an American injustice, admittedly, as a friend told her, 'a dead issue.' But like the true stories of all honest survivors, it reminds us that no one—least of all the innocent—can escape the indignities of the past."]

LaViolette, Forest. Pacific Affairs 47.3 (Autumn 1974): 405–06. ["As a human interest document this book is sharply memorable...." ]

New York Times Book Review , Jan. 13, 1974, 31. ["... their book provides an often vivid, impressionistic picture of how the forced isolation affected the internees. All in all, a dramatic, telling account of one of the most reprehensible events in the history of America's treatment of its minorities."]

Rabinowitz, Dorothy. Saturday Review World , Nov. 6, 1973, 34. ["Mrs. Houston and her husband have recorded a tale of many complexities in a straightforward manner, a tale remarkably lacking in either self-pity or solemnity."]

Rochman, Hazel. "The Asian American Experience: Nonfiction." Booklist , Nov. 1, 1992, 502. ["In a spare, powerful memoir, a Japanese American woman remembers the three years she spent as a small child with her family in the interment camp at Manzanar, and she talks about growing up after the war."]

Schmitz, Terri. "Safety in Numbers." The Horn Book Magazine 78.4 (July 2002): 433–34. ["She provides a clear-eyed, utterly absorbing view of their life in the camp…. This powerful and moving account of a shameful episode in/American history has been adopted for classroom use all over the country."]

Wilson, Robert. Pacific Historical Review 43.4 (Nov. 1974): 621–22. ["... a warm and moving account of the impact of war and the Japanese relocation upon a Japanese family of twelve."]

Footnotes

- ↑ Anthony Friedson, "No More Farewells: An Interview with Jeanne and John Houston," Biography 7.1 (Winter 1984): 50–73; Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Afterword to 2002 edition; Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, "Autobiographical Essay," Contemporary Authors Online , Gale, 2017, accessed on Sept. 19, 2017 at go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GLS&sw=w&u=hono44147&v=2.1&id=GALE%7CH1090047453&it=r&asid=4143d422c771272a74ef05c0f20a6bf0.

- ↑ Elena Tajima Creef, Imaging Japanese America: The Visual Construction of Citizenship, Nation, and the Body (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 100; Ajay Singh, "The Lessons of History," Los Angeles Times , Nov. 6, 2001, accessed on Sept. 18, 2017 at http://articles.latimes.com/2001/nov/06/news/cl-650 ; Greg Robinson, "What I Did in Camp: Interpreting Japanese American Internment Narratives of Isamu Noguchi, Miné Okubo, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, and John Tateishi," Amerasia Journal 30.2 (2004), 55.

Last updated Jan. 5, 2024, 2:18 a.m..

Media

Media