Japanese American World War II military service memorials

Between 1942 and 1945, thousands of soldiers of Japanese descent served in the US armed forces as members of the 100th Infantry , 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). The contributions of these men have since been recognized in a number of locations with honor rolls, memorials to the fallen, monuments to the units, and living memorials. Even while the war was ongoing, a small number of monuments emerged to honor fallen comrades and pay tribute to the service of the men. Yet these early tributes were typically local in nature and few in number. It was decades before nationally visible monuments emerged in the United States.

European Monuments

Ironically, some of the earliest monuments to honor the Japanese Americans appeared in Europe, specifically the areas in France and Italy where the 100th/442nd RCT had the most impact. In the Vosges Mountains of the Alsace-Lorraine region, the 100th/442nd RCT helped liberate the three small towns of Bruyeres, Belmont, and Biffontaine in the fall of 1944. Local residents of Bruyeres were so grateful for their liberation and intrigued by the unique heritage of their rescuers that they wanted to honor the soldiers. In 1947, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) presented a plaque in both English and French honoring the men of the unit, and the townspeople of Bruyeres created a special stone monument in the surrounding Helledraye Forest to display the plaque. This monument became the scene of annual ceremonies on the anniversary of the liberation and also inspired the renaming of the road leading to the site as the "Rue du 442nd Regiment Americain." These commemorations led to the creation of additional monuments in the surrounding hills and the development of a twin cities relationship between Honolulu, Hawai'i and Bruyeres, France.

In addition to their service in France, the men of the 100th/442nd RCT also made significant contributions throughout Italy. In the spring of 1945, a young Italian named Americo Bugliani was a refugee living near the Allied encampment with his parents when he received rations and personal care items from 442nd RCT soldier Paul Sakamoto. The kindness of Sakamoto and other men from both the African American 92nd Infantry and the 100th/442nd RCT inspired Bugliani to dedicate a monument 55 years later in Pietrasanta, Italy. Visitors to the region today can see a statue of Pvt. Sadao S. Munemori , a Medal of Honor recipient, on a marble base depicting the local region as it was devastated by the war, and an image of a mother and child meant to depict hope. The tribute stands in the "Plaza of the Fallen from the Gothic Line" and is the scene of regular ceremonies and memorial services for locals.

In recent years, tributes to individual soldiers have also been erected in Livorno and Tendola, Italy. In 2006, Private Masato "Curly" Nakae Freedom Square was dedicated on the US military installation of Camp Darby in honor of both Nakae and US Army veteran George Watanabe. Pvt. Nakae received the Medal of Honor for his service in August of 1944 near Pisa, Italy, and interpretive panels in his namesake square tell the story of his bravery in both Italian and English. This square is also considered a tribute to Watanabe who served in the US Army more recently and settled in Italy where he pushed for the creation of a memorial to Nakae and generally worked to preserve the story of the 100th/442nd RCT. The following year another memorial was dedicated in Tendola, Italy, to Tadao "Beanie" Hayashi, who died in 1945 while on patrol with his fellow soldier and friend, Sadaichi Kubota. Decades later, Kubota fulfilled a promise to return to the site and worked to create the memorial in honor of his friend.

Local and National Memorials

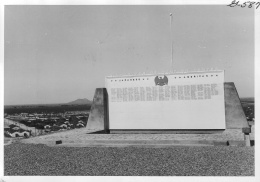

The creation of memorials or monuments in the United States dates back to the war years, and began with the creation of honor rolls within the Japanese American detention camps. According to camp newspapers, at least Gila River , Heart Mountain , Minidoka and Rohwer had created lists of those who had enlisted before the war was over. In the years since the war ended many of the camps have either recreated the original honor roll or created new memorials to those who enlisted from within. Gila River, Heart Mountain, Minidoka, and Rohwer have updated the original tributes while Granada , Poston , and Topaz have built new monuments to honor those who served. These tributes honored the Japanese American soldiers’ service at the local and individual level, though there are also ongoing efforts being made to specifically remember not only those who enlisted, but also those who died during their service.

Dozens of cemeteries serve as the final resting place for members of the MIS and 100th/442nd RCT including the Epinal American Cemetery and Memorial in Dinoze, France, the Florence American Cemetery and Memorial in Florence, Italy, and the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawai'i. Several of these cemeteries also created special memorials in honor of those Nisei who died in combat during World War II. In 1949, Seattle's Lake View Cemetery and Los Angeles' Evergreen Cemetery created memorials specifically honoring the Japanese American soldiers. In 1963, Denver's Fairmount Cemetery did the same honoring not only those who died during the war, but also those locals who have passed away in the years since 1945. Punchbowl Cemetery in Honolulu is the site of five separate memorials to the Nisei. Two are contributions by the living veterans to their fallen comrades of the 100th/442nd RCT, one is from the men of the MIS to their fellow soldiers who died in service, and two were dedicated to the 100th/442nd RCT from the people of Bruyeres and Biffontaine, France, in honor of their liberation. Located as they are in cemeteries, these memorials are fitting tributes specifically to those that lost their lives during service.

In addition to the local tributes to those who died during the war, the residents of Little Tokyo in Los Angeles also wanted to dedicate a memorial to the over 800 Japanese Americans who died during WWII and in all wars since. As preparations began for what would become the Go For Broke Monument , a debate emerged over whether the monument should include the names of all those who served or just those who died. Ultimately, the Go for Broke Monument was dedicated in 1999 in a plaza adjacent to the Japanese American National Museum and listed the names of all Japanese Americans who served during WWII, plus those who had died in all past US wars. The completed structure bore the inscription of 16,000 names with surrounding columns and kiosks to offer information on the units and the Medal of Honor recipients, but this was not a satisfactory product for some in the local community. A new organization, the Americans of Japanese Ancestry World War II Memorial Alliance (the Alliance) formed and within two years created a memorial to specifically honor those of Japanese ancestry who died during the conflict. This monument was dedicated in 2000 and stands in the Memorial Court of the Los Angeles Japanese American Cultural and Community Center alongside memorials to the Japanese Americans who died during the Korean conflict and the Vietnam War.

The question of who should be remembered is one with a variety of different answers depending on the sponsoring organization and local affiliation. The latter decades of the 20th century saw the emergence of both site-specific and broader national monuments in honor of the Japanese American soldiers. For example, local residents and historians interested in preserving the history of the MIS contributions dedicated a historical marker at Camp Savage , Minnesota, while both Fort McCoy, Wisconsin, and Fort Snelling , Minnesota, have created monuments to memorialize the efforts of the Nisei at each site. Representatives of the 100th Infantry have also coordinated in the creation of two monuments, one at Sacrifice Field on Fort Benning, Georgia and a second, called "Brothers in Valor," in Honolulu, Hawai'i.

Perhaps the monument that is the most visible at a national level is the National Japanese American Memorial located on a triangle at the confluence of New Jersey Avenue, D Street, and Louisiana Avenue near Union Station and the Capitol Building in Washington D.C. It took a great deal of work and compromise for the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation (NJAMF) to successfully gain permission for and complete construction of this memorial, but the finished product represents a significant change in the landscape of commemoration for Japanese Americans. Though the vast majority of public recognition of the Nisei contributions had taken place at the individual or local level, this monument, along with the Go For Broke Monument, brought national attention and an acknowledgement that the service of the MIS and 100th/442nd RCT was not only significant for the Japanese American community but also for the country as a whole.

Living Memorials

One of the trends that emerged in monument building in the years following World War II was the creation of living memorials, or facilities that are functional and practical but pay tribute at the same time. There were a number of such living memorials created to honor Japanese Americans beginning in 1946 with the creation of the 100th Infantry Battalion Memorial Building in Honolulu, Hawai'i. While the war was still ongoing, members of the 100th Infantry began collecting donations amounting to $50,000 by the end of the war. Using their donations, the veterans created the 100th Club and purchased several properties before settling at 520 Kamoku Street in 1952. The Memorial Building features numerous medals, plaques, awards, certificates, and trophies as well as a collection of books, documents, and films about the Nisei's military service. The Club's reception hall honors all of the Medal of Honor recipients from the unit and the lounge area and snack bar are regularly visited by local members of the unit who come for conversation and companionship with their former comrades. Renovations were completed in 2011 to roughly double the exhibit space at the Clubhouse and to pay particular attention to remembering the names of all those who served from the 100th Infantry, those who were killed in service, and those who received the Medal of Honor.

Local residents of Seattle had a similar idea during the war that inspired them to create the Seattle Nisei Veterans Memorial Hall shortly after the war ended. Though they have updated, renovated, and added to it over the years, this living tribute to the local Seattle veterans of the 100th/442nd RCT and MIS has lasted many decades. The veterans and locals of the Seattle area have since expanded programming to include educational offerings and speakers' tours, and they have created a Memorial Wall adjacent to the Memorial Hall to honor those who served as well as those who were incarcerated during the war years.

One common type of living memorial that can be found around the world is a garden that is created entirely or at least in part as a memorial to the Nisei military service of World War II. Two such examples are the Normandale Community College Japanese Garden and the Indiana University-Kokomo Peace Garden. Dedicated in 1972, the Normandale Garden is located within 20 miles of the original location of the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) at Camp Savage and is a living tribute to the contributions of the Nisei linguists. The Peace Garden at IU Kokomo is located in Darrough Chapel Park and honors the veterans of the 100th Infantry, the victims of the Pearl Harbor attack, and the detainees. These gardens provide a location for ceremonies or quiet contemplation and offer more functionality than some of the more traditional marble and stone monuments.

Though this is not a comprehensive list of all commemorative mentions of the 100th/442nd RCT and MIS, the sites and monuments listed here provide a good overview of the major monuments and the various trends in their creation. Many of the earliest memorials were actually found in Europe where the discrimination of the US was not as prevalent, though local commemorations emerged early in the United States as well. It was not until the 1980s and later that monuments reached a national level with the Go For Broke Monument in Los Angeles and the National Japanese American Memorial in Washington, D.C. More recent tributes vary from traditional marble monuments to living memorials like club buildings, gardens, and even road and highway names. The emergence of national and prominent memorials coincided with a growing recognition of the significance of the Japanese American story within American history.

For More Information

Ambrose, Stephen E. "A Terrible Idea: The Memorial to the Japanese-Americans." National Review , November 22, 1999.

Forgey, Benjamin. "A Place to Reflect on a Civil Wrong." The Washington Post , September 20, 1997.

Hiura, Arnold T. "Americo Bugliani: One Man's Mission of Thanks." Hawaii Herald , February 3, 1995.

Mattirolo, Chiara. "Community Gathers to Mourn Friend, Passionate Historian." The Outlook (Vicenza, Italy), October 4, 2005.

Moulin, Pierre. U.S. Samurais in Bruyeres: People of France and Japanese Americans: Incredible Story . France: Peace and Freedom Trail, 1993.

Nakagawa, Martha. "Italy to Dedicate Monument in Honor of Nisei Soldiers." Pacific Citizen , April 14-20, 2000.

Patriotism, Perseverance, Posterity: The Story of the National Japanese American Memorial . Washington D.C.: National Japanese American Memorial Foundation, 2001.

Salyers, Abbie Lynn. "The Internment of Memory: Forgetting and Remembering the Japanese American World War II Experience." Ph.D. dissertation, Rice University, 2009.

Spano, Susan. "A French Village's Unexpected Heroes." Los Angeles Times , September 4, 2005.

The Unveiling of an American Story . Los Angeles: Go For Broke Foundation, 1999.

"Yamagata, Naoji. "A Place to Shoot the Bull." In Remembrances: 100th Infantry Battalion 50th Anniversary Celebration, 1942-1992 . Honolulu: Sons & Daughters of the 100th Infantry Battalion, 1997.

Yoshimura, Valerie Nao. "The Legacy of the Battle of Bruyeres: Reflections of a Sansei Francophile." In Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans . Edited by Erica Harth. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. 229–52.

Last updated Oct. 16, 2020, 4:34 p.m..

Media

Media