Literature in camp

Within the confines of War Relocation Authority (WRA) and Department of Justice camps, Japanese Americans wrote and published poems, short stories, and essays in both Japanese and English. In one case, while incarcerated in the Tule Lake concentration camp a Nisei wrote a novel about life behind barbed wire, but it was not published until decades later.

Publications in English

Each WRA camp published an English-language newspaper , and some of those publications occasionally included poems or stories. The murder mystery "Death Rides the Rails to Poston" by well-respected Nisei writer Hisaye Yamamoto was serialized in the Poston Chronicle and is a highlight of these rare creative works in camp newspapers.

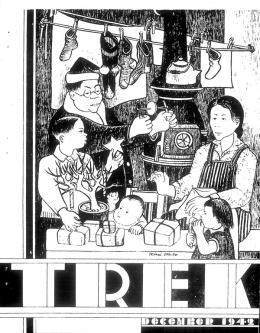

Channeling the talents of many writers who were involved in prewar Nisei literary circles, three camps published English-language magazines which included creative writing: The Pen ( Rohwer ), Tulean Dispatch Magazine (Tule Lake), and Trek ( Topaz ).

A single issue of The Pen was published in November 1943 to mark the one-year anniversary of the Rohwer concentration camp. The magazine includes sections on camp administration and highlights of camp events in the preceding year. The literary section features stories, poems, and essays written by Rohwer prisoners, as well as by white staff members and prisoners of other camps. Given that camp publications were censored, it is surprising that several pieces in The Pen candidly bring up racism and frustration over incarceration. But the censors might have spared them because they end with affirmations of loyalty and a willingness to fight for American ideals of equality.

With George Jobo Nakamura as editor, eleven issues of Tulean Dispatch Magazine were published between August 1942 and July 1943. Each issue includes short stories, poems, and articles on camp life. Reading Tulean Dispatch Magazine , one might never know that Tule Lake was a site of controversy regarding the loyalty questionnaire . Much of the writing in the magazine explicitly or implicitly exhorts prisoners not to be bitter about their incarceration. Because the magazine was an official WRA publication, its contents unsurprisingly are largely uncritical of the camp administration and the incarceration program. But a handful of pieces allude to tensions. "Question 28," by Shuji Kimura, for example, in the April 1943 issue, directly refers to one of the controversial "loyalty questions" and is unusual in its overtly critical viewpoint.

In contrast to The Pen , and Tulean Dispatch Magazine , Trek , published in Topaz, offers a broader array of talents and more complex perspectives. Originally edited by Jim Yamada, a budding writer and UC Berkeley student, and artist Miné Okubo , Trek was published three times between December 1942 and June 1943. A fourth and final issue of the camp magazine, entitled All Aboard , was published in Spring 1944 and edited by Toshio Mori , a Bay Area writer who by World War II had gained some national notoriety. Each issue of Trek opens with a lead article (on camp life or resettlement), followed by stories, poems, essays, articles on the geography and history of the Topaz region, and a women's column. The writing in Trek is more polished and sophisticated than in the other camp magazines, as evidenced by two sensitive short stories by Jim Yamada which appeared respectively in the February 1943 and June 1943 issues and are linked by the same protagonist, a Nisei student at the University of California.

Trek reflects tensions between "optimistic" and "critical" perspectives. "Optimistic" writing is characterized by admonitions to have faith in American democracy. The leading writer of this group is Toshio Mori. In "Topaz, Station," for example, a sketch Mori wrote for the first issue of Trek , the narrator comments that Topaz is "a stopping-off place on the way to progress as good Americans for a better America." Here Mori echoes the motto of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL): "Better Americans in a Greater America." His allusion is not only an optimistic statement but also a political one, given the complex and hostile feelings many Japanese Americans developed about the JACL because of its accommodationist policies.

Because government authorities censored camp publications, writers had to mask their criticisms. "Yule Greetings, Friends" by Jim Oki (using the pseudonym "Globularius Schraubi") is an example of "critical writing" and appeared in the inaugural issue of Trek . A mock scholarly analysis of "evacuese," the mixture of Japanese and English spoken by Issei and Kibei , the piece hints at intra-camp tensions. Through puns and references to dogs, Oki makes veiled allusions to accusations that some Japanese Americans informed on fellow prisoners to camp administrators. Such individuals were called " inu ," the Japanese word for "dog."

Even more subtle, the finely crafted poems of Toyo Suyemoto which appeared in each issue of Trek and in All Aboard offer what literary scholar Susan Schweik calls examples of "resistance and critique embedded within the forms and diction of poems which appear apolitical." "Gain" is an example:

I sought to seed the barren earth

And make wild beauty take

Firm root, but how could I have known

The waiting long would shake

Me inwardly, until I dared

Not say what would be gain

From such untimely planting, or

What flower worth the pain?

Given the context in which the poem appeared, Suyemoto's nature imagery takes on metaphorical significance. The "barren earth," for example, can refer not only to the desert of Topaz but also what an imprisoned Nisei might consider the desert of America.

Writing in Japanese

May Sky: There is Always Tomorrow, An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Haiku is a collection of 300 haiku written in WRA and Department of Justice camps by members of two prewar California haiku clubs: Delta Ginsha Haiku Kai in Stockton and Valley Ginsha Haiku Kai in Fresno. Violet Kazue de Cristoforo (nee Kazue Yamane), a member of the Valley Ginsha, compiled and translated the poems into English.

Delta Ginsha poets were incarcerated in the Stockton Assembly Center and then at the Rohwer concentration camp. In both places, they continued to write and to meet to discuss their work. During the war, Kyotaro Komuro, leader of the Delta Ginsha writers, compiled two volumes of their haiku: one consisting of 525 poems written at the Stockton Assembly Center, and the second a collection of 1,000 haiku written at Rohwer. Both volumes were published by the Rohwa Jiho Sha , the newspaper at Rohwer.

Valley Ginsha members were incarcerated at the Fresno Assembly Center and then at the Jerome concentration camp, where they formed the Denson Valley Ginsha, named after a nearby town. Some of their poems were published in the Utah Nippo , the Japanese language newspaper of Salt Lake City.

Many members of the Denson Valley Ginsha were transferred to Tule Lake after it was designated the camp for individuals who answered the loyalty questions negatively. Along with poets from other camps, they formed the Tule Lake Valley Ginsha. May Sky includes some their haiku, which de Cristoforo describes as "plaintive and, at times, defiant."

In 1987, de Cristoforo self-published the book Poetic Reflections of the Tule Lake Internment Camp 1944 , a collection of poems she wrote while incarcerated at Tule Lake.

Despite an explicit WRA policy of "Americanization" for Issei and Kibei, administrators at several camps allowed the publication of self-financed literary magazines in Japanese. At Gila, the Kibei-dominated Gila Young People's Association published three issues of a literary magazine called Wakoudo between May and August 1943. After members of that group were transferred to Tule Lake, they published seven issues of Dotō (July 1944-June 1945), which feature stories, essays and poems by Kibei and Nisei. Also at Tule Lake, between March 1944 and July 1945, a group of young writers in collaboration with Issei poet Bunichi Kagawa produced nine issues of the peer-reviewed literary magazine Tessaku (Iron Fence), which includes fiction, essays, social criticism, and poetry. Similar Japanese-language magazines were produced in Heart Mountain ( Hāto Maunten Bungei , 6 issues between December 1943 and September 1944) and Poston (P osuton Bungei , 25 issues edited by Keizan Yagata between February 1943 and September 1945).

Jiro and Kay Nakano translated into English and edited tanka (a Japanese poetic form) written by four Issei from Hawai'i who were imprisoned in military and Department of Justice internment camps. Their book Poets Behind Barbed Wire: Keiho Soga, Taisanboku Mori, Sojin Takei, Muin Ozaki , records the writers' impressions of being arrested, their observations of camp life, the ironies of war, and their thoughts of freedom. Poet Keiho Soga , owner of the Nippu Jiji in Honolulu, founded the Santa Fe-shisha Tanka Club while interned at the Department of Justice camp there. Taisanboku Mori and his wife Ishiko, while interned at the Department of Justice camp in Crystal City , founded, along with Sojin Takei, the Texas-shisha tanka club. Nagareboshi ("Shooting Star") is a collection of 334 tanka written by club members which was published in October 1945. After his return to Hawai'i, Takei published in 1946 a collection of his own wartime poems, Areno ("Wilderness").

Sole Novel Written in a Camp

Treadmill by Hiroshi Nakamura is the only novel about Japanese American wartime incarceration written during World War II in one of the camps. Born in Gilroy, California, in 1915, Nakamura graduated from UC Berkeley in 1937. He was an English editor for a large Tokyo newspaper and worked in Manchuria before returning to the U.S. Like the characters in his novel, he was incarcerated in the Salinas Assembly Center , Poston , and Tule Lake, where he completed Treadmill while also working in the Community Analysis Section .

In 1974, two years after Nakamura's death, Professor Peter Suzuki discovered the manuscript for Treadmill in the National Archives and shepherded it to publication.

The novel centers on 20-year-old Teru Noguchi of Salinas and her family as they are forced to move from their home to various camps. The book depicts rumor mongering and resentment towards self-appointed community leaders (specifically the JACL), the breakdown of family structure in camp, and the complex reasons why individuals would answer "no" or "yes" to the loyalty questions. The book could benefit from editing. But it is nevertheless a vivid portrait of camp life.

Although Treadmill claims the distinction of being the only published novel that was written in a Japanese American concentration camp, numerous authors since World War II—Japanese Americans and non- Nikkei —have focused their literary imaginations on the incarceration of Japanese Americans to produce novels, memoirs, short stories, poems and plays.

For More Information

de Cristoforo, Violet. ed. May Sky: There is Always Tomorrow, An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Haiku . Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press, 1997.

———. Poetic Reflections of the Tule Lake Internment Camp 1944 . Self-published, 1987.

Honda, Gail, ed. Family Torn Apart: The Internment Story of the Otokichi Muin Ozaki Family . Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai'i, 2012.

Kobayashi, Junko. "Bitter Sweet Home: Celebration of Biculturalism in Japanese Language Japanese American Literature, 1936-1952." Diss. University of Iowa, 2005.

Nakamura, Hiroshi. Treadmill . Oakville, ON: Mosaic Press, 1996.

Nakano, Jiro, and Kay Nakano, eds. Poets Behind Barbed Wire: Keiho Soga, Taisanboku Mori, Sojin Takei, Muin Ozaki . Honolulu: Bamboo Ridge Press, 1983.

Opler, Marvin K. and F. Obayashi. "Senryu Poetry as Folk and Community Expression." Journal of American Folklore 58:227 (January–March 1945): 1–11.

Schweik, Susan. A Gulf So Deeply Cut: American Women Poets and the Second World War . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991. [Part Three of this book focuses on Nisei women writers, particularly Toyo Suyemoto.]

Soga, Yasutaro (Keiho). Life Behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai'i Issei . Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008.

Last updated Aug. 24, 2020, 2:35 p.m..

Media

Media