Manzanar Free Press (newspaper)

| Publication Name | Manzanar Free Press |

|---|---|

| Camp | Manzanar |

| Start of Publication | April 11, 1942 |

| End of Publication | October 19, 1945 |

| Mode of Production | mostly printed |

The Manzanar Free Press was the longest running of the concentration camp newspapers, spanning Manzanar 's time as an "assembly center" as well as a War Relocation Authority camp. It was also one of three typeset, printed newspapers. Its run was interrupted for twenty days in December 1942 due to the riot/uprising at Manzanar.

Background and Staffing

The War Relocation Authority camp newspapers kept incarcerated Nikkei informed of a variety of information, including administrative announcements, orders, events, vital statistics, news from other camps, and other necessary information concerning daily life in the camps. (See Newspapers in camp ). Story coverage was comparable to what one might typically expect of a small town newspaper, with nearly identical coverage in all ten camps of social events, religious activities (both Buddhist and Christian), school activities and sports , crimes and accidents, in addition to regular posts concerning WRA rules and regulations. Nearly every paper included diagrams and maps of the camp layouts and geographical overviews to allow residents to get a bearing of their locations; payroll announcements, instructions on obtaining work leaves and classified ads for work opportunities; lost and found items; and some editorial column that was reflective of its Japanese American staff editor. Reporters and editors were classified as skilled and professional workers respectively and received monthly payments. The wage scale was set at $12 or $16 a month for assistants and reporters and $19 for top editors, although no labor was compulsory. All ten camps had both English and Japanese language newspapers. Despite its democratic appearance, the camp newspapers in reality were hardly a "free" press. All newspapers were subject to some sort of editorial interference, in some cases even overt censorship, and camp authority retained the power to "supervise" newspapers and even to suspend them in the event that they were judged to have disregarded certain responsibilities enumerated in WRA policy. [1]

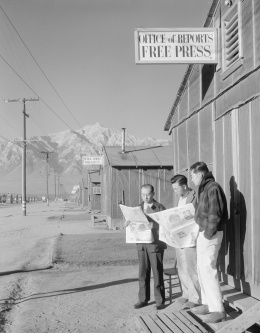

The Manzanar Free Press was launched on April 11, 1942, by a group of ambitious ex-newspaper men and women in what was first a Wartime Civil Control Administration "assembly center." The center was later converted into a War Relocation Authority concentration camp, which retained the Manzanar Free Press as its community bulletin. The paper began as a four page bi-weekly that was typed and mimeographed, before growing into a six-page bi-weekly. Manzanar's growing population and additional daily activities led to the paper increasing production to a tri-weekly newspaper. By July 22, 1942, the staff acquired a printing press and began releasing a typeset, printed newspaper.

The name of the newspaper itself implies freedom of speech and the presence of a democratic media, which the administration and editors frequently alluded to. In the paper's first printed issue on July 22, 1942, they wrote: "We want to repeat again that the Free Press belongs to the people of Manzanar, that, instead of being merely the mouthpiece of the administration, it strives to express the opinions of the evacuees in the solution of immediate and forseen problems." [2] Despite the enthusiasm, former Manzanar Free Press editor Sue Embrey admitted that aside from the enjoyment of the work and the relatively liberal minded staff, "The human element did not appear in the printed pages. There were no personal views of the writer. We did not write about what was happening to us, the poor food, the poor medical care, the lack of privacy, having to take showers together. We knew if we wrote about a certain thing, it wouldn't get in the paper. The complaints of the internees were not voiced in the Free Press." [3]

Editing the paper during its infancy stage were journalists Joe Blamey, Chiye Mori, Dan Tsurutani, Roy Hoshizaki, Tom Yamazaki, and Sam Hohri. Former Rafu Shimpo editor Togo Tanaka was added to the staff by May 1942 and in the summer of 1942, well-known journalists such as Harry Honda, Mary Kitano, Carl Kondo, and Helen Aoki were feature writers for the Free Press . A Japanese language section was added on July 14, 1942, though each issue was accompanied by an English translation of its contents.

Coverage Highlights

From the beginning, the Manzanar Free Press promoted a pioneer spirit to its readers, envisioning the mass removal and confinement as a chance to settle new communities in the wilderness, and immediately began to distribute information, often directly from WRA bulletins, on organizing a working system for the camp.

The Free Press covered events such as the founding of the Children's Home in May 1942, an institution unique to Manzanar. Criminal activity was another staple, with the paper reporting that gambling and speeding the two main offenses under investigation by Manzanar police in 1942, while reports of gang fights and thefts (especially from shower rooms) were on the rise. However, it was not mentioned in the Free Press on May 16, 1942 when a resident, Hikoji Takeuchi, was shot and seriously injured by a guard, with wounds that indicate that he was shot in the front. [4]

With the institution of a loyalty questionnaire and subsequent segregation of the "disloyal" from the "loyal," the Free Press ran articles that attempted to explain the purpose of the segregation process, and then published procedures for those leaving or arriving at Manzanar as people shifted from camp to camp.

Several articles covering resistance outside Manzanar, including the April 1944 arrest of nine Kibei at Fort McClellan, Alabama, for refusing to obey army orders were included in the Free Press that spring. (See Military resisters .) On June 28, 1944, the newspaper reported on the "Biggest Mass Trial in Wyoming's History," a major story covering sixty-three Nisei from the WRA camp in Heart Mountain , who were charged and found guilty of violating the Selective Service Act, in the only formally organized resistance to the military draft. (See Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee .) Of related interest was the story run on August 5, 1944, claiming the arrest of eight men, including James Omura , former English editor of the Rocky Shimpo newspaper of Denver, who were charged with an indictment for conspiracy in counseling other Japanese Americans or for direct evasion of the Selective Service Act.

The Manzanar Riot/Uprising

In November 1942, a general strike roiled the Poston , Arizona camp. In response, the Free Press ran a sidebar mourning the news of the Poston strike as "another setback," by drawing negative press to the camps, without investigating the root cause of the camp protest. The paper also discussed inmate dissatisfaction with the controversial camouflage net factory, which was in operation from June to December 1942 and a November 30, 1942, arson at the General Store amid grievances against the community co-operative store due to "smoldering resentment against the Cooperative by some of the people for quite a while, caused chiefly through misunderstanding of the workings and policies of the Enterprises."

On December 5, 1942, Fred Tayama , leader of the Japanese American Citizens League , was attacked and seriously injured. When Harry Ueno , a cook who had been active in organizing kitchen workers and who was a vocal critic of the JACL, was arrested for the attack, a center wide riot/uprising ensued. For twenty days, the Manzanar Free Press was shut down entirely, publishing its first issue after the incident on Christmas Day, December 25, 1942, which made no mention of the attack, arrests, or military police shootings. (See Manzanar riot/uprising ; Homicide in camp .)

Immediately following the December uprising, an almost completely new staff took over the Manzanar Free Press , which included Sue Kunitomi, Ray Hayashida, Reggie Shikami, and Mas Hama, and the paper was changed back to bi-weekly.

Early January 1943 issues of the Free Press ran excerpts from other American newspapers under the column "From the Nation's Press" related to the 'incident at Manzanar' and other issues related to WRA camp conditions, but otherwise it feigned normalcy by focusing on stories of the new clothing allowance, offerings at the cooperative stores, and developments in the growing resettlement project.

Shutting Down

When Nisei eligibility for the draft was restored, most of the paper's stories covered the exploits of the all-Nisei 100th / 442nd Regimental Combat Team along with lists of their military honors and the death count. Meanwhile controversy surrounding the political turmoil at Tule Lake and the fate of those who elected for repatriation to Japan lingered. By late March 1944, the first glimmers of reopening the West Coast area to Japanese Americans were reported in the papers, although polls from the Los Angeles Times and other papers indicated public opinion was still largely in favor of barring all Japanese from returning.

On December 17, 1944, the mass exclusion orders were rescinded, allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast, and by early January 1945, the first Manzanar residents begin re-populating their former homes in California, Oregon, and Washington. While the Free Press was dominated with successful stories of relocation, the newspaper also covered numerous acts of discrimination and hate crimes against returning Japanese Americans between January and June 1944. (See Return to West Coast ; and Terrorist incidents against West Coast returnees .)

As the final days of Manzanar wound down, the Free Press primarily functioned as a board for classified ads for jobs and housing. The last issue of the Manzanar Free Press ran on October 19, 1945, and the camp closed permanently on November 21, 1945.

Footnotes

- ↑ Takeya Mizuno, "The Creation of the 'Free Press' in Japanese American Camps," Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78.3 (2001), 514.

- ↑ Specific issues referred to in the text can all be found by searching the Densho Digital Repository at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-125/ .

- ↑ Diana Meyers Bahr, The Unquiet Nisei: An Oral History of the Life of Sue Kunitomi Embrey (New York: Palgrave MacMillian, 2007), 68.

- ↑ Hikoji Takeuchi, Manzanar ID Card, Manzanar National Historic Site, 2008, http://www.nps.gov/manz/forteachers/id-booklets.htm .

Last updated Dec. 11, 2023, 7:30 p.m..

Media

Media