Saburo Kido

| Name | Saburo Kido |

|---|---|

| Born | October 8 1902 |

| Died | April 1 1977 |

| Birth Location | Hilo, HI |

| Generational Identifier |

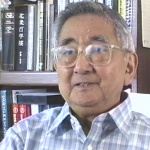

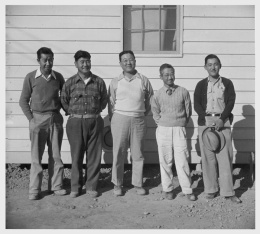

Attorney and wartime president of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). An older Nisei born and raised in Hawai'i, Saburo Kido (1902–77), was an early supporter of the JACL and led the organization through the turbulent war years, surviving two physical attacks while incarcerated at the Poston , Arizona concentration camp. After the war, he and his law partners A. L. Wirin and Fred Okrand took on several key civil rights cases, challenging alien land laws, school segregation, and fishing rights, among other issues.

Nisei Leader

Saburo Kido was born in Hilo, Hawai'i, in 1902, the third son of Sannosuke and Haru Kido. He came to California to attend the Hastings College of Law at age 19 and graduated with his degree in 1926. A sake brewer and bookkeeper, his father lost his business with the advent of prohibition, and the couple returned to Japan after Saburo left for California, never to see him again. He settled in San Francisco and began a law practice. In 1928, he married Mine Harada, a Nisei from Riverside, California. Like a number of older Nisei leaders, he was a Republican, fluent in both Japanese and English, and advocated the idea of the Nisei being a "bridge of understanding" between Japan and the U.S. He also had a purported friendship with anti-Japanese agitator V. S. McClatchy . JACL house historian Bill Hosokawa describes him as "slight, short, dapper, and he had never lost his Hawaiian accent." [1]

Kido was among a group of relatively successful Nisei who came together to form what would become the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). He was also a key figure in the founding of the Nikkei Shimin , the precurser to the Pacific Citizen , the JACL's house organ newspaper. As he wrote in the first issue of the paper in 1929,

The publication can be the connecting link between the first and second generation Japanese by trying to dissolve any misunderstanding which may be existing at the present time. It can portray to the American public what we, American citizens of Japanese ancestry, are thinking in regards to our duties as citizens as well as our diverse problems. It can give expression to what is considered true American ideals and guide the growing generation to become American citizens we can all be proud of. [2]

He continued to support and write for the paper, penning a column titled "Timely Topics." He also authored a front page column of the same name for the Shin Sekai newspaper in the 1930s. Later, as JACL president, he played a key role in the Pacific Citizen moving beyond being a house organ for the JACL to being a national Japanese American newspaper during the war and hired Larry and Guyo Tajiri as editors.

In 1940, he took on the presidency of the JACL, in the shadow of the march to war with Japan. In 1941, he pushed for the hiring of Mike Masaoka as the JACL's first staff person, favoring both his assertive personality and his connection to influential white men such as Elbert Thomas. [3] As the JACL's leader, he met frequently with the FBI and other intelligence agencies and also met with special presidential investigator Curtis Munson .

War and Aftermath

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Kido sent a telegram to the President on behalf of the JACL that read, "[I]n this solemn hour we pledge our fullest cooperation to you, Mr. President, and to our country... now that Japan has instituted this attack upon our land, we are ready and prepared to expend every effort to repel this invasion together with our fellow Americans." [4] With Masaoka and other JACL leaders, he led the JACL to its controversial decision to cooperate with the impending mass forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and their subsequent incarceration in concentration camps. At a JACL Emergency National Council Meeting on March 8, 1942, Kido told the delegates to "keep our chins up," that "we are gladly cooperating," and expressed gratitude to the government, noting that "we are glad that we can become wards of our government." [5] He and Masaoka subsequently worked with War Relocation Authority leaders to give their input on the mechanics of administering the camps for incarcerating Japanese Americans. This strategy of cooperation and of putting the best possible face on the situation, exposed bitter divisions in the community.

On a personal level, Kido and his family were among those who "voluntarily evacuated" from San Francisco in Military Area 1 to a small town near Visalia in Military Area 2 , only to face forcible removed anyway, when Japanese Americans were evicted from both areas. He and Mine and three young children were able to get permission to go to Poston, Arizona camp, hoping to join members of Mine's family. As was the case with other JACL leaders, he came under physical attack from fellow inmates, both in September of 1942 and again in January of 1943. The second attack, perpetrated by eight men, one of whom wielded a club, landed Kido in the hospital and hastened his family's departure from Poston. [6] The Kidos resettled in Salt Lake City, where he taught Japanese for the military at Fort Douglas, Utah and worked for the JACL. He continued to write in the Pacific Citizen . In 1944, he expressed his opposition to the draft resistance movement at Heart Mountain , writing ". . . no one will be sympathetic or condone 'draft dodging.' This is one of the worst crimes that any citizen can commit." [7]

At the same time, he became an important advocate for civil rights as an attorney, joining forces with former American Civil Liberties Union attorney A. L. Wirin in representing George Ochikubo in his challenge of exclusion in 1944. [8] After the war, the firm of Wirin, Kubo, [Fred] Okrand were involved in several landmark civil rights cases. In 1945, they represented fisherman Torao Takahashi in his challenge of a wartime law that prohibited Issei —under the guise of "aliens ineligible to citizenship"—from being granted fishing licenses by the state of California, a case that saw the U.S. Supreme Court eventually overturn the California law. (See Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission .) In 1947, the firm took on the appeal of the Oyama v. California case to the Supreme Court that resulted in a landmark decision that effectively made the alien land laws unenforcible. They also worked on amicus briefs on behalf of the JACL in cases that eventually brought down segregated schools and restrictive housing covenants. [9]

In 1948, Kido left the firm and opened his own office in Los Angeles. He remained active with the Pacific Citizen and even printed the paper for a time, when he took ownership of another newspaper, the Shin Nichibei , for a time in the 1960s. In 1970, he retired, closing down his Los Angeles law office due to failing health. [10] He passed away in San Francisco in April of 1977.

For More Information

Hosokawa, Bill. JACL in Quest of Justice: The History of the Japanese American Citizens League . New York: William Morrow, 1982.

Rawitsch, Mark. The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream . Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Yoo, David. Growing Up Nisei: Race, Generation, and Culture among Japanese Americans of California, 1924-49 . Foreword by Roger Daniels. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Footnotes

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1969), 195. Biographical sketch compiled from Bill Hosokawa, JACL in Quest of Justice: The History of the Japanese American Citizens League (New York: William Morrow, 1982); Hosokawa, Nisei ; Mark Rawitsch, The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 142; Jere Takahashi, Nisei/Sansei: Shifting Japanese American Identities and Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997); and David Yoo, Growing Up Nisei: Race, Generation, and Culture among Japanese Americans of California, 1924-49 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

- ↑ Nikkei Shimin , October 15, 1929, 2. Accessed on Jan. 11, 2018, http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-1-1/ .

- ↑ Takahashi, Nisei/Sansei , 87.

- ↑ Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 71.

- ↑ Deborah K. Lim, "Research Report Prepared for the Presidential Select Committee on JACL Resoluation #7 (aka 'The Lim Report')," 1990, 27, accessed on June 16, 2012, www.javoice.com/Lim.doc.

- ↑ For a detailed account of the second attack, see Rawitsch, "The House on Lemon Street, 217–26.

- ↑ Lim, "The Lim Report," 61.

- ↑ Eric Muller, American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 107–33.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 126–37, 200–11.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , October 9, 1970, p. 5.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 5:03 p.m..

Media

Media