Tanforan (detention facility)

This page is an update of the original Densho Encyclopedia article authored by Lewis Kawahara. See the shorter legacy version here .

| US Gov Name | Tanforan Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | San Bruno, California (37.6167 lat, -122.4000 lng) |

| Date Opened | April 28, 1942 |

| Date Closed | October 13, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from the San Francisco Bay area of California. |

| General Description | Located 12 miles south of San Francisco, California. |

| Peak Population | 7,816 (1942-07-25) |

| Exit Destination | Topaz |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

The Tanforan Assembly Center was located on the site of the Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California. It was the second largest of the temporary WCCA camps, located 20 miles south of San Francisco, near the San Francisco International Airport. The camp was occupied from April 28 to October 13, 1942, a total of 171 days. Holding Japanese Americans mostly from the San Francisco Bay Area, its peak population was 7,816. All in all, 8,033 Americans of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated at Tanforan, 64 per cent of whom were U.S. citizens. About half of the inmates lived in former horse stalls. 98 per cent of the 7,824 Japanese Americans in Tanforan who were transferred to "relocation centers" were sent to the Central Utah WRA camp also known as Topaz. The site was subsequently used as a training camp by the VII Army Corps. A shopping center sits on the site today, a small historical marker commemorating its World War II history. [1]

Site History/Layout/Facilities

Site History

Tanforan was a racetrack from September 4, 1899, to July 31, 1964. It was named after Toribio Tanfaran, the grandson-in-law of Jose Antonio Sanchez, the grantee of Rancho Buri Buri. The Rancho was built in 1889. The Tanforan Racetrack had a varied history, encompassing many of the greatest names in racing including thoroughbreds Seabiscuit and Citation and numerous notable owners and trainers. In addition to horse racing, Tanforan also had dog, motorcycle, and automobile racing tracks. It returned to horse racing when betting was legalized again in California in 1932. During World War I, Tanforan was used as a temporary military training center.

Immediately prior to Pearl Harbor, a portion of the property was used by the U.S. Navy as a special advance personnel depot for the Western Division Naval Facilities Engineering Command. After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army took control. Work to remodel the 118-acre racetrack into a temporary concentration camp for persons of Japanese ancestry started on April 7. Initial construction was completed on April 25, 1942. Construction continued until May 25, costing the army $1,188,000, approximately $150 per inmate. [2]

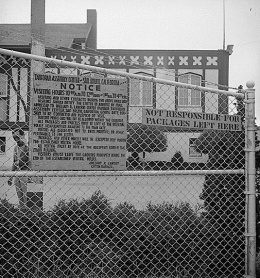

The camp was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with armed military police on guard at all times. Searchlights on the guard towers, in addition to fence lighting, were planned, but when the army engineers notified the WCCA that shipment would not possible before September 15, the WCCA canceled the request. [3] Eucalyptus trees surrounded the racetrack, and the barbed wire fence helped to block the view of the barracks. The trees also flanked the main entrance on El Camino Real in front of the wooden fence and the barbed wire fence that blocked off the view of the track. The compound was bound by Noor Avenue on the North, Forest Lane on the South, El Camino Real on the West, and the Southern Pacific Railroad on the East. [4]

Layout and Housing

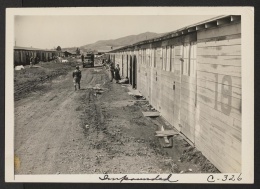

Tanforan had about 180 barracks with about half of them (76) built in the racetrack infield. 135 of those barracks were built for accommodation, measuring 20 x 100 feet. They were subdivided into smaller "apartments." In addition, twenty-six stables, located to the east of the infield, were converted into barracks. There were eventually 18 buildings used as mess halls and kitchens, 18 smaller shower buildings with 278 shower heads, 24 latrines, six laundry buildings, and three hospital buildings. [5] Residential barracks were finished by the end of May and showers and latrines by mid-June, while work on the road system, the sidewalks, and street lighting lasted until July (flood lights at the front gates were completed by June 8). [6] Cleaning the premises of debris was a major task taken over by the inmates, who also did most of the work on the roads and walkways. [7] Thus Tanforan retained the character of a construction site well into June, which is captured well by Dorothea Lange's photographs.

The first arrivals found out that their "barrack" was in fact a stable, and their "apartment" a horse stall, as the regular barracks were not yet finished. Altogether twenty-six converted horse stables were remodeled as living quarters, housing about 3,700 people, roughly one half of all the Japanese Americans at Tanforan. Most stables consisted of fifty stalls, twenty-five facing north, and twenty-five facing south. Three to six people occupied a stall that had formerly accommodated one horse. Each stall was about 10 x 20 feet and empty except for a number of army cots. Most stalls had linoleum floors that had been laid over manure-covered boards. The smell of horses hung in the air, and the whitened corpses of insects still clung to the hastily white-washed walls. [8]

Each stall was divided into two sections by a swinging half-door. The front section, used to store the fodder, had two small windows on either side of the door. The rear section was windowless. A single electric bulb hung from the ceiling. The walls to the adjoining stalls stopped a foot short of the sloped roof, presumably to provide for better ventilation for the horses. This arrangement deprived the occupants of all but visual privacy. Apart from cots the only things the army issued were one straw tick and one blanket per person. People over sixty years of age received cotton mattresses, and some horse stall occupants received them, too, as compensation for their inferior living quarters. [9]

Those arriving during the second half of May were assigned to the newly built barracks. By the end of May, 135 barracks, each measuring 20 x 100 feet, housed about 4,000 people, around 30 people per barrack. They comprised either five apartments each for six persons, or ten apartments for three persons each. All barracks had plywood partitions, about 8 feet high, leaving an open space between each partitioned room so that even subdued conversation disturbed neighboring compartments. The advantages of barracks over stables were a controversial topic: although the barracks didn't smell like the stables, they were badly insulated, so that on sunny days they became unbearably hot, and chilly during the nights. [10] After the new barracks were finished at the end of May, families were redistributed as to better use the available space.

Single men were housed on the second floor of the grandstand, which served as a makeshift dormitory during the first month. The hall where the pari-mutuel clerks once sold their $2 tickets housed approximately 500 men, most of them unmarried Issei . The San Mateo County Health inspectors eventually prohibited further dormitory use of the hall, and by the end of May, all singles had been relocated to the barracks. The dormitory subsequently served as a makeshift classroom for the high school. [11]

Bath and Laundry Facilities

As in all WCCA camps, during the first month in particular, there was a lack of sanitary and laundry facilities. [12] In Tanforan, latrines, wash rooms and laundries were located in separate buildings. Each latrine contained eight toilets, some separated by partitions, some not. By the end of May, after vehement protests, the army installed partitions in all latrines, but no doors. Everyone able to do so went to the toilets in the grandstand, where there was more privacy. (Plus, men had the choice between "Gents" and "Colored Gents" facilities.) Washrooms contained eight showers, partitioned, but again without doors or curtains. Hot water regularly ran out. [13] A report by the U.S. Public Health Service from June 2 stated: "A major problem in all centers has been and continues to be sanitation. That so few epidemics have occurred from unsanitary conditions has been due to the heroic efforts of the management of the centers, the County Health Departments and the Japanese medical staff." [14] Latrines and wash rooms were eventually finished in mid-June.

By the end of May the army had finished building six laundries. Due to the numerous families with children in Tanforan they featured ubiquitous lines. As the hot water usually ran out by 9 a.m., many Nikkei got up at 3 in the morning to do their washing, as the camp authorities usually did not enforce the night curfew. [15]

Once the Army Engineers had withdrawn, the inmates took it upon themselves to make the camp more habitable. A muddy pool, located in the northwestern corner, was transformed by volunteer inmate labor under the direction of architect Roy Watanabe, into a miniature aquatic park, complete with green lawn and shrubbery, a foot bridge, islands, three rock gardens, sand pits, promenades and benches. During the opening ceremony on August 2, it was renamed "North Lake," and work to beautify it continued throughout August. [16] Another addition was a small garden west of the Hollywood Bowl that included a greenhouse. [17]

For the purpose of community elections the camp was divided into 5 precincts. Precinct 1 included Barracks 1-10; Precinct 2, Barracks 13-22; Precinct 3, Barracks 23-54; Precinct 4, Barracks 55-102; and Precinct 5, Barracks 103-180.

Mess Halls and Feeding

During the first weeks there was only one mess hall. Located beneath the grandstand and capable of holding 500 people, it served food to over 3,000 people. Inevitably long lines formed before each mealtime, and even though the opening of eleven more mess halls by the end of May eased the situation somewhat, lines remained an integral part of camp life.

The mess halls that were built during May were furnished with backless benches and picnic tables. For the first ten days, the army served A Rations and B Rations. (A Rations consisted of semi-perishable and perishable food items requiring refrigeration, food service equipment and personnel. B Rations were served in the field and consisted of canned and dehydrated foods not requiring refrigeration.) The menu was comprised of lima beans, canned food (for instance Vienna sausages and corn), bread, potatoes, chili con carne, and occasionally Jell-O. Sociology student [Tamotsu Shibutani |Tom (Tamotsu) Shibutani] recorded the food served in the main mess hall during the second week: [18]

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | |

| Thursday, May 7 | Stew (peas, carrots, meat) two slices of bread, tea | Two tablespoons macaroni, 1/2 potato, coffee | |

| Friday, May 8 | Three pancakes, mush, toast, coffee | Green vegetables, 1/2 potato, boiled bread | Rice, fish (about three mouthfuls), two slices of bread |

| Saturday, May 9 | Three pancakes, mush, two slices of bread | Corned beef and cabbage (canned), two slices of bread | Roast pork (tiny), potato, canned beans (string), dried figs |

Some

Issei

expressed their desire for Japanese dishes such as

ochazuke

(rice soaked in green tea, served with pickled vegetables). Others stayed away for two or three meals, relying on food sent in from friends.

[19]

By the end of May, there were eleven mess halls in operation, each catering to 600 to 850 persons. The former main mess under the grandstand was then used for the feeding of 300 Japanese Americans in the works and maintenance crew. [20] The lack of tableware was somewhat alleviated, as some Nikkei brought their own dishes and washed them themselves. Some also brought along their own chopsticks. A ticket system was introduced so that people could not eat more than once. Later during June, Tanforan introduced "family style service," meaning that families were served food at their table according to their needs and did not have to wait at the counter. [21] Also, as in the other camps a shift system was introduced with designated eating times at 7 and 7:30 a.m., 12 and 12:30 noon, 5 and 5:30 p.m.

In the course of their imprisonment, the Nikkei made the mess halls more habitable by decorating the walls with watercolor paintings and flags. Some mess halls had fresh flowers on every other table, at first donated by a Caucasian florist nurseryman, and later from the camp's own nursery. In addition, mess halls acquired nicknames such as Lakeside Inn, Lettuce Inn, Brass Rail, Coconut Grove, Knotty Pine Inn, and Skyroom. To show their appreciation towards the cooks and mess hall staff, who often put in more than the required 44 hours week for a meager wage of $8 per month, the inmates developed various customs. For example, after particularly tasty meals, all would gather and yell, "1, 2, 3, banzai!" In another mess hall, the Nikkei collected $83 to present to the cooks. [22] However, shortcomings and deficiencies remained, in particular a lack of dairy products and Vitamins A, B, B1, and C. [23] This was hardly surprising since the average cost of feeding a person in Tanforan was 37 cents a day. (In comparison, the army spent 50 cents a day on active soldiers).

Camp Population

The bulk of the population of the Tanforan Assembly Center came from the San Francisco Bay Area, including Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and San Francisco counties. The majority of the inmates came by Greyhound Bus. Some Japanese American inmates drove their own cars to Tanforan, which were subsequently confiscated by the Federal Reserve Bank.

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Counties | Civil Control Station | Number |

| 19 | May 1 | Contra Costa and Alameda | Berkeley | 1,182 |

| 20 | May 1 | San Francisco | Bush Street, San Francisco | 1,892 |

| 27 | May 7 | Alameda | Oakland | 832 |

| 28 | May 7 | Alameda | Oakland | 662 |

| 34 | May 9 | Alameda | Hayward | 1,211 |

| 35 | May 9 | San Mateo | San Mateo | 891 |

| 41 | May 11 | San Francisco | Buchanan Street, San Francisco | 848 |

| 81 | May 20 | San Francisco | O'Farrell Street, San Francisco | 279 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than forty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

The first group of inmates arrived on April 28, a "volunteer" contingent of 421 workers to handle the primary needs of transforming the Tanforan racetrack into an "assembly center." In the following days, numerous buses unloaded their human cargo from the Bay Area. Three days later over 3,000 Japanese Americans had arrived, and by May 10 Tanforan housed 7,496 people. By May 20, with the arrival of the last major group of Nikkei, the population had risen to 7,796 and remained at that level for almost four months.

| Date | Inducted | Total Population after Induction |

| April 28 | 421 | 421 |

| April 29 | 631 | 1,052 |

| April 30 | 1,092 | 2,144 |

| May 1 | 919 | 3,063 |

| May 6 | 907 | 3,969 |

| May 7 | 606 | 4,575 |

| May 8 | 1,102 | 5,677 |

| May 9 | 1,007 | 6,684 |

| May 10 | 812 | 7,496 |

Source: Wartime Civil Control Administration, Bulletin No. 12, March 15, 1943, page 100.

The incoming buses stopped in an area where military police and administrative buildings were located. The inmates had to walk between a cordon of armed guards to enter the compound proper. While soldiers inspected the baggage for contraband—any weapons, straight-edged razors and liquor—the Nikkei were directed to an area beneath the grandstand where a cursory medical check was made. A nurse looked into their mouths and checked if they had been vaccinated for smallpox; men were also checked for venereal disease.

[24]

After filling out a series of forms each family was assigned their living quarter.

[25]

Bachelors were sent to the second floor of the grandstand, which served as a dormitory for over 500 people. Because housing was scarce, smaller families had to share a single unit.

| Profession | Percentage |

| Clerical, sales and kindred | 14.0 |

| Domestic workers | 10.0 |

| Housewives (part time) | 9.1 |

| Operatives | 9.0 |

| Service workers | 5.4 |

| Farmers, farm laborers | 5.0 |

| Professional | 4.3 |

| Property managers and officials | 4.2 |

| New workers (no training) | 4.2 |

| Craftsmen and foremen | 3.3 |

| Semi-professional | 2.7 |

| Unemployable (students, over 65, disabled) | 25.3 |

| Total | 96.5 |

Source: Doris Hayashi diary, p 229, Aug. 9, 1942, JERS Reel 17, Slide 206.

Tanforan was open for a total of 171 days. The peak population was 7,816 on July 25. There were 64 births and 22 deaths.

| Births | Deaths | Jails, INS Internment | Furlough | Mixed Marriage | Other | |

| Entering | 64 | 49 [26] | 36 | |||

| Leaving | 22 | 21 | 38 | 36 |

Source: Wartime Civil Control Administration, Bulletin No. 12, March 15, 1943, pages 100-03.

When news of the transfer to a remote inland camp spread, many Japanese Americans applied to return to their homes, either to settle business matters, or to obtain clothing and personal belongings. The camp director forwarded all requests to the WCCA headquarters in San Francisco, which eventually allowed some inmates to return under army guard to make final arrangements before their deportation. One of them was the artist

Miné Okubo

.

[27]

Almost all of Tanforan's inmates were assigned to the Central Utah "relocation center," also known as Topaz. The trip from Tanforan to Topaz would take two nights and one day by train. An advance work group of 214 left Tanforan on September 9 and arrived at Topaz on September 11. Regular transfers commenced on September 15, with 500 Nikkei leaving daily. Hand baggage—which to the camp manager's frustration had increased in many cases, including self-made furniture and items brought from outside friends—was sent in freight trains, usually two days in advance. [28]

| Departure Date | Number | Remaining Population |

| September 9 | 215 | 7,576 |

| September 15 | 502 | 7,075 |

| September 16 | 485 | 6,590 |

| September 17 | 514 | 6,077 |

| September 18 | 499 | 5,587 |

| September 19 | 509 | 5,071 |

| September 20 | 521 | 4,550 |

| September 21 | 500 | 4,050 |

| September 22 | 518 | 3,532 |

| September 26 | 526 | 3,006 |

| September 27 | 514 | 2,492 |

| September 28 | 516 | 1,977 |

| September 29 | 516 | 1,461 |

| September 30 | 532 | 931 |

| October 1 | 534 | 400 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

A few were sent to other WRA camps. Among them were student researchers in the [[Japanese [American] Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS)| Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study]], such as

Charles Kikuchi

and

Tamie Tsuchiyama

, who went with their families to

Gila River

and

Poston

respectively.

The evacuation was completed on Tuesday, October 15, when the "rear detail" of 308 Japanese Americans was entrained at 5 pm. Thus, all had left the West Coast, except 51, 42 of whom were in the San Mateo County Hospital, five who were admitted permanently to the St Agnes State Hospital, and four who were taken by law enforcement agencies. [29]

Staffing

As was true at many of the temporary concentration camps, a good portion of the staffing came from the ranks of the WPA, including the first camp manager, William Lawson. He was a state administrator of the WPA of Northern California, a position he returned to after he had seen the camp through the critical induction phase. Those who worked under him described him as a charismatic, practical and tactful politician, "mild mannered, [...] with a willing ear to suggestions which made him well-liked by both Caucasian and evacuee employees." [30] On June 4, he was succeeded by his assistant, Frank Davis. Correspondence shows that Davis was primarily interested in pleasing the military and oblivious to the plight of the detainees. The Nisei working for the JERS study described him as a "gruff individual with no showmanship, nor desire for popularity." [31]

Other key staff:

Police Chiefs: Floyd Arrowood, R.W. Arnold (until May 28); Gerald "Jerry" Easterbrooks (until June 26), L.B. Hughes, Balfour Davies, Lester White (from Tulare)

Chief Steward: John Fogarty

Service Division Supervisor: George Green

Finance and Records Supervisor: T.K. Miller

Housing and Feeding Supervisor: Willard Speares, followed by Peter Cooper

Works and Maintenance Supervisor: William Beck

Health Section Supervisor: Fred Woelflein, replaced by Donald Wild on June 24

Education Supervisor: Frank Kilpatrick

Personnel relation officer: William Gunder

Supplies Supervisor: Mr. Kelly

Postmaster: Gill Juchert

Tanforan's administration was divided into five divisions: (1) The "Administrative Division" acted as liaison to the WCCA headquarters in San Francisco which prescribed the basic regulations for all "assembly centers." (2) The "Works and Maintenance Division" maintained all physical facilities of the camp, from repairs to electric, water and sewer systems, to buildings and mess hall tables. (3) The "Mess and Lodging Division" was responsible for housing and feeding, as well as policing, cleaning and furnishing supplies for laundries, showers and latrines. (4) The "Finance and Record Division" kept all accounts and records. (5) The "Service Division" was the one with the closest contacts to the inmates. It included the recreation and education programs, supervised employment, and was responsible for issuing paychecks and scrip books.

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

Like most aspects of camp life, community government was an ambiguous matter. While the WCCA never planned for a community government, some form of advisory councils formed in most of the temporary camps. In Tanforan, the democratic experiment went a bit further than elsewhere. Most activities regarding co-determination took place from May to July. In July the WCCA begun cutting back on the community government experiments, and by August the looming transfer ended all efforts to from a genuine community government.

Tanforan's first director, William Lawson, declared in the first issue of the camp newspaper that he wanted the camp to be "as self-governing as possible." [32] At that time the inmates had informally selected among themselves one house manager for every 150 people in camp. Paid at the $12 wage rate they were the first point of contact for everyday needs and also the primary channel through which prisoners and keepers communicated. On May 5, Lawson invited the house managers into his office and explained that he would like to have feedback from each part of the camp. He divided Tanforan into five precincts and asked the house managers to assign one person per district for regular meetings with the administration. Following an informal election among the house managers, each precinct determined one representative. Together they formed a temporary council (also called an advisory board), that met weekly with Lawson to discuss matters pertaining to camp life. [33]

As this elite group did not have broad community support, it was agreed to hold elections as early as possible to form some kind of representative body. Lawson suggested that Issei and Nisei should be eligible to vote, while only U.S. citizens could be allowed to hold an office. [34] In early June, Lawson returned to his former job at the WPA and was replaced by his assistant, Frank Davis, who turned out to be far less supportive of the inmates' grass roots project. Still, preparations went ahead and on June 6 the Totalizer announced that on June 16 there was to be the general election of a five-member advisory council. The right to vote was conferred to all inmates who were at least 21 years of age, while councilmen had to be 25 years of age and citizens of the United States. [35]

Eventually 19 candidates were admitted to the race. [36] To provide a forum for candidates to advertise their policy and vie for votes, the camp director permitted each precinct to have one election rally during which Japanese could be spoken. The rallies were held in barracks which were usually filled to capacity (500 persons). As eligible Issei outvoted eligible Nisei 3:1 the campaigns usually evolved around winning the vote of the first-generation immigrants. Political ideology played only a minor role in Tanforan's first election. What counted most was the ability to appeal to both the first and the second generation and fluency in English and Japanese. Integrity, charisma, and social networks were the imperative ingredients to success.

On election day, June 17, over 80 percent of the eligible inmates cast their votes. The winners were Toshimi Ogawa, Ernest Satoshi Iiyama, Frank Yamasaki, Albert Kosakura, and Vernon Ichisaka. [37] Three of the five councilmen were progressives, two of them Nisei and one Kibei (Iiyama). Interestingly enough, the only councilmen who had run on the "JACL ticket" was Vernon Ichisaka from the fifth precinct, testifying to the decline of the JACL's reputation. [38]

The minutes of meetings between the democratically elected council and the camp director show the confident, almost aggressive appearance of the councilmen. Most points raised during the various meetings concerned everyday needs. The minutes also show that the camp administrators were principally opposed to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. For example, when asked if it would be acceptable when an inmate received visitors in his or her apartment who had a common interest in poems, Davis replied that the person ought to notify his house manager, who would then notify the chief of the police chief, who in turn would notify his men of the meeting being held. [39] Furthermore, the camp director often stated that he needed first to consult the WCCA headquarters in San Francisco. [40]

After the success of the first election, a constitution was drafted (confirmed by Davis on July 13), providing for a "legislative congress" to be composed of members elected from each precinct on the basis of one assemblyman for each 200 residents. Everyone aged 21 and older was allowed to vote. [41] By July 25, a total of 80 candidates had been nominated for the 38 offices in Tanforan's Legislative Congress. The election was scheduled for July 28. [42] However, the preparations for Legislative Congress marked the turning point of political activities. Starting on July 1, the WCCA had issued a series of regulations restricting self-government, such as allowing only citizens to vote or hold any elective office. [43] The inmates soon realized that the army considered any form of community government null and void. The army only allowed for an advisory committee chosen by the camp director. By mid-August, only two candidates had submitted their applications for an advisory committee post, and at that point the inmates and the camp director agreed to abandon elections and focus on the upcoming transfer instead. [44] Nevertheless, activities in Tanforan regarding the formation of a community government remain a remarkable testimony to the democratic spirit of the incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Education

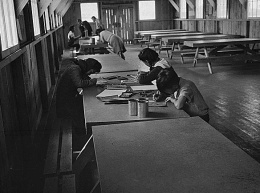

Tanforan's education program was perhaps the most extensive in all of the temporary WCCA camps, partly due to its long lifespan and partly due to the high percentage of people with college or university background. The education program was divided into three branches: academic (kindergarten, elementary school, high school, and adult education), cultural (art, music, flower arranging), and extra-curricular (cooperative education, first aid, town hall debates). In the absence of a formal education program, resident teachers staffed all schools. By the end of June, about 40 percent of all inmates either taught or attended classes. The educational department was headed by Frank Kilpatrick, a graduate of Berkeley's Boalt Hall Law School.

Voluntary primary school registration started on Monday, May 25. By the end of the day, 75 percent of the approximately 1,700 students between the ages of six and eighteen had registered, with the number approaching 100 percent within days. The next day, four classes for children between the ages of six and eight were begun in four unused mess halls. The furnishing was provisional. Blackboards were made from painted plywood. The mess hall benches and tables were far too high for the children, and there were virtually no supplies. However, three-fourths of the children brought their own pencils, pads, school records and textbooks, and due to supplies from schools outside, only a lack of textbooks remained. [45]

High school classes started on June 15 with about 700 students registered. Classes continued for thirteen full weeks until September 11. The high school was staffed with twenty teachers, all with college degrees, but only three with previous teaching experience. Classes took place inside the grandstand after the bachelors had been moved out. [46] The setting was somewhat bizarre, as Charles Kikuchi observed: "A painted sign 'Tanforan High School' sticks up from the mutual windows and a girl stands behind it giving out information instead of selling mutual racing tickets. The unerased race results high in the air lend a further racing touch." [47]

Ninety percent of the elementary and high school students were advanced by the schools which they attended prior to exclusion. [48] As at several of the other "assembly centers," some graduating high school seniors who missed their graduations back home got a graduation ceremony in the camp. In June, San Mateo and Burlingame High Schools awarded graduating Nisei students their high school diplomas after Principal W. T. VanVoris had visited the camp on May 30 with six faculty members to give a special final examination to the incarcerated students. Later, on June 13, the Sequoia High School principal came and presented diplomas and awards to nine Nisei students. Other Nisei received their diplomas by mail. [49]

In addition to elementary school and high school, several nursery schools were created for children aged two to five. The first kindergarten opened on May 18, and three more soon followed. Out of 372 pre-school age children, 287 registered. [50] Open from Monday through Saturday 9:00 to 11:30 a.m., the kindergarten sought "to free the mother without taking her place," as the camp newspaper advertised. [51] Again the physical setup was marked by inadequacies: initially there were no chairs, tables, toys, towels, dishes or toilets. [52]

In Tanforan, there were an estimated 250 college graduates and 250 college students. [53] Because the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council's program was still in its beginnings, only about ten students left Tanforan to continue higher education outside the Western Defense Command . Two of them were forced to return to Tanforan after nativist protests at their destination. [54] In addition, three Kibei volunteered to go to the University of Colorado, at Boulder, to teach Japanese to navy men. [55]

Complementing nursery school, elementary school, and high school classes, a program for adults was set up, including Americanization classes in English, civics, and history. During the first week over 225 Issei and Kibei signed up for English classes scheduled twice a week, and eventually some 500 participated. Classes were limited to ten students each, with the stress being on English conversation. [56]

Most teachers in the adult education program were bilingual and had taught Japanese before the exclusion (adult classes, along with church services, were the only meetings in which Japanese language was allowed). The adult education program was appreciated in particular by Issei women, many of whom for the first time in their lives found the leisure time to pursue interests beyond the sphere of family duties.

Twenty days after Tanforan opened, artists began cleaning up Mess Hall 14, which soon became the Tanforan Art School. The San Francisco Bay Area had a number of gifted Japanese American artists, among them Miné Okubo , Chiura Obata , and George and Hisako Hibi , whose expertise made art classes popular. Obata headed the school since he had been an art professor at the University of California prior to incarceration. The Tanforan Art School officially opened on Monday, May 25, with 16 instructors and 300 students. [57] There were flower arranging (ikebana) and paper folding (origami) classes that allowed the residents to practice traditional Japanese arts. In addition, Obata gave weekly lectures on the fine arts which were hugely popular among all age groups. By the time Tanforan officially closed, more than ninety-five classes had been taught. [58]

To sum up, 40 percent of all inmates took part in in some classes of the education department:

| Opening Date | Original Enrollment | Final Enrollment | Increase | Number of Teachers | |

| First Aid | May 18 | 230 | 50 | -180 (Students graduated) | 1 |

| Art | May 25 | 500 | 636 | 136 | 15 |

| Music | May 25 | 280 | 498 | 218 | 9 |

| Elementary | May 25 | 550 | 658 | 108 | 26 |

| Junior high | June 15 | 225 | 233 | 8 | 9 |

| High school | June 15 | 670 | 680 | 10 | 18 |

| Adult education | June 18 | 282 | 558 | 276 | 14 |

| Co-op education | July 6 | 10 | 112 | 102 | 1 |

| Kindergarten | July 7 | 101 | 101 | 5 | |

| Flower arrangement | July 23 | 80 | 125 | 45 | 2 |

| Total | 2,928 | 3,651 | 100 |

Apart from the academic program, the educational department organized weekly "town hall" discussions. A regular Wednesday night feature, town hall meetings provided the Nikkei with a platform to debate various issues related to their current situation. For example, the first town hall meeting, held on May 27, featured the topic "How may we better cooperate to improve Tanforan?" Other topics included "The advisability of marrying in a relocation center," "The role of religion in the relocation center," and "Relocation: stagnation or rehabilitation?"

[59]

Town hall meetings were organized by Nisei and also chiefly attended by them.

Medical Facilities

The army proclaimed that medical care was free, but even for a prison, health service was lacking. During the first ten days, there was one woman doctor serving the needs of 3,000 inmates. Newborn babies had to be put in cardboard boxes. Dentists had no tools, not even a chair, and the optometrists could do nothing besides conduct eye tests and send out glasses for repair. [60] According to the Tanforan hospital report of May 18, many cases of German measles were coming into camp as new inmates arrived. [61] The main concern of the Public Health Service was to vaccinate the inmates against typhoid, smallpox, and diphtheria. After a month most of the population had been inoculated. [62]

Though most diseases were not critical, the inability to treat them properly added to the discomforts of camp life. Many detainees had a cold most of the time, and due to malnutrition, skin problems were widespread. Digestive problems persisted throughout the five months in which Tanforan was in operation, and there were at least two or three major outbreaks of diarrhea. [63]

In its early weeks, Tanforan was additionally hampered by its hospital manager, Fred Woelflein. Woelflein was unpopular due to his lack of commitment and perceived incompetence. Inmates criticized him as somebody who "did not know anything about medicine [...] and did not know anything about administration." [64] On June 1, a prematurely born baby died because the hospital manager was unwilling to cut the red tape and transfer the mother to the San Mateo County Hospital, which was only a twenty minute ride away from Tanforan. [65] The Japanese head physician Dr. Hajime Ueyama refused to cooperate with the hospital manager and threatened to resign if the administration did not show more support for the hospital. The camp manager, seeing no other option, eventually released Woelflein but also removed the recalcitrant Issei physician to Tule Lake . [66] Woelflein's successor, Dr. Donald Wilde from the San Mateo County Hospital, was not only an experienced doctor himself but also successful in pressuring the army to improve health standards. [67]

Library

Unlike other WCCA camps, where the library operated under the Education Department, in Tanforan it was part of the Recreation Department. In May 1942, the WCCA contacted California's assistant state education superintendent, asking him to call on schools to turn over obsolete and worn books for use in the camps. This was about all the WCCA undertook to establish libraries. [68] The library opened on May 4, exactly one week after the camp received its first groups of inmates, and was housed in a 20 x 100 feet barrack. The library started with four children's books and ten comic books donated by inmates. Kyoko Hoshiga, a Nisei graduate of Mills College and head librarian of the Tanforan library, solicited help from her former teachers. Mari Ogi and Ayame Ichiyasu served as librarians, Nobuo Kitagaki, Ray Kagami, Ida Shimanouchi, and Alice (Ayako) Watanabe as assistant librarians. The Issei Yoshiharu Tsuno was custodian. [69]

Donations came from the San Mateo County Library (400 books), the Berkeley Public Library (173 books and twice as many magazines), the Alameda County-, Oakland-, and Burlingame public libraries, San Francisco and San Jose state teacher colleges, and Stanford University. Private donations were facilitated by Berkeley's YMCA, YWCA, and Friends Service Committee. Mills College librarian Evelyn S. Little provided donations and advice, personally visiting the "assembly center" on several occasions. [70] Recreation director Leroy Thompson helped secure army approval for library requests.

By August 8, the library had catalogued 4,250 adult books. Library use peaked in the week of August 15, when Tanforan inmates made 3,871 visits to the library and checked out 1,503 items. The most popular books were William Shirer's wartime bestseller, Berlin Diary, and a handbook on making model boats that was "nearly thumbed to death" by the camp's many model boat builders. [71]

The library also featured a storytelling program by Yoshiko Uchida, who later became a respected author. A Ph.D. thesis on "assembly center" libraries rated Tanforan's library as the best among the fourteen libraries established in the WCCA camps. However, there were no books in the Japanese language although one-third of Tanforan's population was used to reading Japanese. Even before the camp administration enforced the ban the library had only one book in Japanese, a novel by Kan Kikuchi. The purge of Japanese-language books was a heavy blow to Issei morale who were already at disadvantage when it came to recreational activities. (Sacramento was the only assembly center whose library had a Japanese-language section). [72]

Camp Newspaper

Like fifteen of the sixteen WCCA-run camps Tanforan had it's own mimeographed newspaper, the Tanforan Totalizer . It was published weekly over the duration of nineteen weeks and kept inmates abreast of news in the camp. The first four page issue was published on Friday, May 15. The following weeks each of the 2,043 family units in Tanforan received a copy of the Totalizer delivered free of charge to its stall or barrack door. [73] By Issue 8 the page count was increased to ten, with subsequent issues averaging that number. The nineteenth and final issue, published on September 12, comprised 26 pages.

The newspaper office was located in Room 4 of the Grandstand area. About twelve Nisei worked for the newspaper, six of whom were paid. The Totalizer staff consisted of Taro Katayama (editor-in-chief); Bob Tsuda, Jim Yamada, and Charles Kikuchi (associate editors); Bill Hata (sports); Ben Iijima (recreation); Alex Yorichi (kitchen); Lillian Ota (women); Albert Nabeshima (copy boy); Yuki Shiozawa, Sam Yanagisawa, Marguerite Nose, Emiko Kikuchi, and Yuri Oshima (technical staff); Bennie Nobori and Nobuo Kitagaaki (art); and Alex Yorichi (circulation). [74]

Following army regulations, the Totalizer was published exclusively in English. Likewise, instead of formulating a newspaper policy, the WCCA instead provided a press relation representative (i.e. censor) "who saw that news items were confined to those of actual interest to the evacuees." [75] In Tanforan this was George McQueen, who shared the task of censorship with the camp director. All in all, the Totalizer staff recorded 16 "main instances" of censorship. Every article was checked at least three times by Davis and McQueen before it was released. [76]

Administrative announcements usually filled the first two of the Totalizer' s ten pages. They pertained to visiting policies, roll call regulations, clarifications on scrip book allowances, absentee voting information for the state primaries, and disclaimers of persistent rumors. The greater part of the paper listed succinctly annotated schedules of daily activities. About two pages were dedicated to sports and other leisure activities. Recreation and entertainment took up another two pages, minimum, featuring listings of intramural leagues, movies, dances, talent shows, variety shows, and classical concerts. The education section, which took up about one page, included announcements of adult classes and the gist of the weekly town hall discussion. Furthermore, each issue contained information on central services, such as the opening hours of the hospital, the post office, the lost and found bureau, the library, and the schedules of the various church services.

The Totalizer regularly contained announcements that were written to amuse its readers. For instance, the newspaper reported about a resident who jumped into the lake to catch a duck to win a bet, or about "the spectacle of mothers using adjoining laundry tubs to bath their shower-shy but otherwise unembarrassed younger children," or about the "Infield Odysseys" of men who got lost after escorting home their girlfriends. [77] Absent, by contrast, were reports on conflicts within the camp community or between inmates and their keepers, although we know from private accounts that many such conflicts occurred. The only exception was the mentioning of a 17-year-old Nisei who had thrown a rock against a sentry tower. [78] The story was only published after rumors spread that the military police had imprisoned the teenager, causing angry demands by the some Nikkei that their fellow inmate be released. There were at least two escape attempts that went unreported. [79]

There were also columns reflecting on camp life. "With the Womenfolk" was such a column, giving practical advice on "womanly" issues, for example, how to treat dry skin, how to protect against the sun, how to get greasy dishes clean, and how to fight the all-present dust. A similar column was "Tips of the Week." Almost all these columns followed the same pattern: First, they state the inconvenience of a particular situation. Second, selected inmates explain how they deal with the situation. Third, it is resolved that the situation does not really pose a problem. There were several polls on Tanforan's living conditions that also fit this mold.

The display of patriotism to the United States was a major cornerstone of the Totalizer's agenda: patriotic ceremonies such as a camp-wide flag raising ceremony on May 26 and the celebration on Independence Day were covered at length. And when 21-year-old Bill Kochiyama used a $2,000 inheritance to purchase $1,900 worth of war bonds, "to do my part in the war effort," as he put it, he received due commendation on the Totalizer's front page. After the story was reprinted in the Berkeley Gazette the camp director agreed to increase the Totalizer' s page count from six to ten. [80] Other patriotic acts included acclamations for volunteer blood donors, reports on the collecting of tin cans, and the storage of grease for the production of nitroglycerin, always pointing out that "the Center had an oar in the national war effort." [81] Many of the biographical sketches on prominent inmates also had a patriotic overtone, such as the one on Tatsu Ogawa, 46, one of twenty American Legion members in Tanforan who earned his citizenship after fighting in the First World War. [82]

Religion

Religious activities enjoyed more freedom from administrative influence than other activities. According to a JERS study, "Religion is the one institution in Tanforan which apparently is not censored." [83] Church services were exempted from the Japanese language ban that was otherwise strictly enforced. Although spoken Japanese was allowed during services, Japanese religious publications were impounded along with other language materials. Towards the end of August, the WCCA eventually sent a list with religious books in Japanese that were allowed for use by the Buddhist and Catholic churches at Tanforan. However, most Japanese-language services must have been conducted without them. The Protestant churches at Tanforan used exclusively English publications. [84]

Most people dressed up when they attended church services, with women and girls often wearing silk stockings and high heels. On May 3, the first Sunday after Tanforan's opening, Protestants and Catholics held their first service in two vacant mess halls. Two weeks later, Buddhists and the Seventh Day Adventists held their first services. The need for spiritual sustenance was so overwhelming that at the first few Sundays "there was standing room only at both the Japanese and the English service." [85] However, the interest in religion waned towards the end of August, as many young people were drawn towards the various social activities competing with religious services. The Buddhist reacted to the loss of young people by announcing special dancing classes for their members. [86]

No matter the denomination, services were held in puritanical surroundings. Only the Catholic mess hall featured benches, which some inmates attributed to the fact the director of the service division was Catholic. [87] Protestants and Buddhists together made up 90 percent of the Japanese Americans, comprising 60 and 30 percent of the population respectively. [88] Both cooperated on various occasions. The Mother's Day program, for example, was initiated by a Methodist minister, but during the program several Buddhist and Catholic priests spoke as well.

Both Christians and Buddhists invited Caucasian ministers who were allowed to stay for the duration of the services. Buddhists were even more dependent on religious workers from the outside because most Buddhists priests, considered pro-Japanese and subversive, had been interned prior to the incarceration of the Nikkei in WCCA camps and were only gradually "released" to join their families in the WCCA and WRA camps. In Tanforan, a Caucasian priest, Frank Boden Udale who was ordained as a Buddhist priest under the name of Shaku Kyosen, came from San Francisco every Sunday to conduct the service. The San Francisco Buddhist temple also donated an organ, piano and public speaking system, gifts that all denominations shared. [89]

Recreation

Recreational activities served to some degree as an outlet of energies in a repressive climate, providing a momentary escape from concentration camp life with its unresolved tensions, uncertainties and perceived senselessness. By the end of June, there were some 150 volunteers working for the recreation department, spread over eight barracks and six acres of playgrounds. [90]

Sports programs included basketball, baseball, softball, boxing, tennis, football, tennis, horse shoes, sumo , table tennis, and badminton. Schools and churches generously donated equipment. [91] There was also a nine-hole golf course in the racetrack infield next to the tote betting board. [92] Mah jong and board games were also offered. Sumo wrestling and Japanese board games like go were approved by the administration. Talent shows and dances were another form of entertainment that were popular, although they created some tensions with Issei mothers complaining about their daughters staying out too late. The following excerpt from the diary of JERS researcher Charles Kikuchi illustrates the wide gamut of activities eventually developed at Tanforan:

I could see about five baseball games in progress. Near the barbershop in the infield a lot of fellows were pitching horseshoes [...]. Next to them [...] the Sumo wrestlers were occupied. About 100 persons were sailing boats on the lake. Great crowds stand around the edge of the lake looking on, especially at the man who gives rides to kids in the boat he has built. The builder of the big sailboat is a former captain of a fishing schooner. Henry Fujita, the national fly-casting champion, and his son usually come out to the lake on Sunday afternoons to practice. The new lake is more a scenic spot where couples go strolling over the bridge or sit on the benches under the transplanted row of trees around the edge of the lake. A fire tower is being constructed [... near one end of this lake for the firemen to practice on [...]. Sunday is also a big day for tennis, two courts have been laid out on the tracks up by the post office, and there are always lots of golfers going around the miniature 9-hole golf course on the infield. For those who prefer milder activity, there are the weekly bridge tournaments. The rest of the people go visiting each other or else have visitors in the grandstand. [93]

The recreation department also organized weekly dance classes. While Kibei where more inclined to folk dancing, the more avant-garde Nisei favored the jitterbug. [94]

In order to counterbalance these light activities, the recreation department also hosted a cultural program. Weekly talent shows, quiz shows, variety shows, and kite contests attracted mainly Nisei, while Issei preferred classical concerts, featuring works by Schumann, Streabbog, Bach, McDowell, Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Puccini, and Gershwin. [95] Serving as a magnet for all generations were baby contests, beauty contests, and a "Playhouse Petite" featuring a comedy, a drama, a pantomime farce and several piano, violin and dance numbers. There was even a dance band in Tanforan, consisting of two alto saxes, one tenor sax, three trumpets, one trombone, one baritone, piano, drums, and a guitar. Hawaii-born Nisei organized a Hawaiian night featuring an orchestra consisting of a steel guitar, two ukuleles, two Spanish guitars and a vocalist. There was a male chorus dressed in hula skirts made of crepe paper. [96]

A group of inmates interested in vaudeville shows organized a satire on camp life, including a few sideswipes at the administration. Some paragraphs were promptly censored but there were still enough jokes left to delight the audience. [97]

Movie nights, too, fell under the responsibility of the recreation department. A 16 mm movie projector, sound equipment and several educational films were loaned by the San Mateo Tuberculosis and Health Association. Each person was allowed to visit one of the three shows per week. Movies presented included slapstick comedies like Bud Abbott and Lou Costello’s Hold that Ghost , and The Boys from Syracuse , a Broadway musical. The Devil and Miss Jones with Jean Arthur, a Hollywood classic that was nominated for two Oscars, was more serious, as was the drama Hoosier Schoolboy with Mickey Rooney, and the Tim McCoy Western Gun Code . Cartoons and the principal plays of the 1941 football season complemented the program. Inmate accounts describe the motion picture showings as far from a regular cinematic experience, but that in particular children and Issei, possibly because they had no previous cinematic experiences, were eager to see them nevertheless. [98]

Not all activities were formally organized. Those who simply wanted to escape the bustle of the racetrack could be found at the grandstand, a popular place to meet with friends, have a private dice game, bask in the sun, meditate, or have a nap. Knitting was a popular pastime for women and was even taken up by some of the young men. [99] One advantage of the stable area was the fertile ground, resulting in numerous victory gardens where inmates grew turnips, cucumbers, lettuce, string beans and sugar peas to supplement their camp diets. [100] . In addition, two hobby shows presented the work of artists and craftsmen, including paintings, knitted garments, needlecraft, wooden handicraft articles, miniature house models, jewelry, sailboats, home-made candy, and flower arrangement displays, all attesting to an impressive outlet of creative energies. [101] Even the usually reserved camp director noted in a report to the WCCA that the exhibition caused "extremely favorable comments from the administrative personnel and a limited number of outside business personnel who witnessed the exhibit." [102]

Store/Canteen

The army generally prohibited private enterprises in their camps. One exception was the center store which opened in early May. The store was run by a Caucasian businessman who was obliged by WCCA regulations to "supply the needs of men, women and children at the lowest cost possible." [103] When the inmates complained that the store was constantly out of stock, Camp Director Frank Davis agreed to set up a non-profit canteen, which was opened on May 23 in the northeast corner of the grandstand. [104] It carried toilet articles, newspapers, cigarettes and groceries such as peanuts, marshmallow bars, animal cookies, graham crackers, ginger, chocolate, and lemon and vanilla snaps. Much sought-after goods that were seldom available included ice cream, Bireley’s grapeade, tomato juice, and Kleenex. Coupon books were issued by the administration as the sole means of payment. In the week starting July 10, the average daily sales were nearly $1,300. [105]

Starting in June inmates were given monthly allowances in coupons to pay for community services such as the center store, shoe repair shop and barber shop. The monthly coupon allowance was $1.00 for inmates under 16, $2.50 for inmates over 16, $4.50 for married couples, and a maximum of $7.50 for families. [106] The first clothing issue shipment arrived on August 28, a few days before the transfer to WRA camps began.

Visitors

The inmates could receive visitors daily, except Monday, in the reception hall of the grandstand, from 10 to 12 in the morning and from 1 to 4 in the afternoon. Due to the proximity to their former homes, by the end of May, there were almost 500 visitors every Sunday. For those who didn't own a car, the trip could be made from San Francisco by Greyhound or by the Mission Street Car.

People who came to see the inmates included Japanese with special permits to work outside: Dr. Yanaga and Prof. Nahanura, both teaching Japanese to navy men; Mari Okazaki who worked in the WCCA headquarters in San Francisco, and Chiyo Nao who worked as translator for CBS. The majority of visitors, however, were former employers of Japanese Americans, fellow students and teachers from universities, and friends from the YMCA and YWCA. Art Professor Chiura Obata was regularly visited by his students. Among the prominent visitors were Peter Ray from Duke Ellington's band, Helen Gahagan Douglas, a noted California liberal, anthropologist Margaret Mead, and many more. [107]

Visitors brought food, but also ironing boards, brooms, wash tubs, toilet paper, Coca Cola, and soap. While all packages were opened and visitors were casually searched, enforcement was rather lax. Visitors were not allowed to enter the compound proper but some inmates managed "to sneak visitors off to the stable (under some pretext)." [108] Likewise, talking through the fence, although forbidden, was occasionally tolerated by the guards.

Increasing numbers of visitors—over 1,000 people came between May 14-24 to visit with their former neighbors and friends—and presumably lax rules led the administration to take up actions to restrict visiting. [109] Beginning on July 1, visitors had to fill out an application and were issued blue badges before they were allowed to enter the compound. Waiting time averaged 45 minutes. Leaving the visitor area in the grandstand was now impossible.

There was racial profiling too, as guards were required to check "Negroe visitors" closely and keep separate files on them. [110] Another visitor group receiving close attention was Dr. Dorothy Thomas, a professor of rural sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, and her staff from the recently founded JERS project. After the guards saw notes being passed between Thomas and her Japanese American informants, they stepped in confiscating the notes. Thomas and her Nikkei informants were interrogated. After this, Thomas and her associates needed written permission by the WCCA headquarters in order to enter the camp. Other blacklisted visitors included the above-mentioned Helen Douglas. [111]

On August 7, visiting rules were tightened once more. The visiting area was now divided by mess hall tables spread the length of the hall. Internal police roamed the hall to make sure no notes or contraband were passed. Visitors were asked more questions, and waiting times increased even more. No vegetables, staple food products or perishable products brought by visitors were allowed (mainly Chinese takeaway food), with the exception of fresh citrus or deciduous seasonal fruits such as apples or oranges. [112] The system was not only criticized by the incarcerated but also by numerous outside visitors who had to wait an hour or longer, especially on Sundays. Camp Director Davis reasoned that following "specifically each provision" made complaints inevitable but promised that he would follow through nevertheless. [113]

Other

As at other "assembly centers," many inmates took on jobs that helped keep the camp running at paltry monthly wages set at $8, $12, and $16 for unskilled, skilled or professional positions. By the end of August, some 2,500 inmates were on the payroll. Many inmates resented being paid far less than white workers doing the similar work, for instance, an inmate chief cook earned $12, while a white cook earned between $175 and $225 per month.

There were two camp-wide searches. The first took place on June 22 and 23 in order to find contraband that was missed during induction. Contraband included Japanese literature, curved handsaws, kitchen knives, rubbing alcohol, large scissors, baseball bats, short-wave radios, flashlights beyond a certain power and a few other articles. The inmate advisory council urged the camp director to let the Issei keep at least translations of Western fiction, but Davis remained adamant. Thus, a translated Victor Hugo, if found, was confiscated as contraband. [114] A second search was conducted on September 5, this time stricter and under army supervision, to make sure that no contraband would be smuggled to the WRA camps. [115]

Every day at sunrise Tatsui Ogawa and Guy Uyama, U.S. Army veterans of World War I, unfurled the American flag at the center flag pole. On Saturdays and Sundays, trumpeters joined in the ceremony with the playing of two official army pieces, "To the Colors" and "Retreat." [116]

On June 17, a twice daily roll call was introduced at Tanforan following army orders. Signaled by the sound of a siren, the daily head count took place at 6:40 a.m. and at 6:25 p.m. [117] The camp director agreed to transfer the responsibility of the daily count to the inmates. Every house manager appointed several house captains to take care of the task. In the morning the house captains counted the residents as they entered the mess hall, and in the evening they were checked at their stalls and rooms. After about ten minutes they blew a whistle to signal that everybody was allowed to leave their rooms. [118] The task was undertaken with varying degrees of thoroughness, all in all rather lax. [119] Still, many inmates found it humiliating and unnecessary. Ben Iijima wrote, for example: "It's a terrific nuisance and silly and makes me feel more as though I were in a concentration camp. It hurts one’s pride to be counted each morning and afternoon." [120] Another Nisei wrote to a friend outside: "It’s asinine, but it’s army’s orders. Imagine making such a count when we are enclosed within barbed wire fence and guards walking every 50 feet and sentries in watch towers every 100 yards with guns ready to kill." [121]

The army ordered a curfew from 10 p.m. to 6 p.m. during which all inmates had to be in their living quarters. Camp Director Davis, in consultation with Police Chief Easterbrooks and the inmate advisory council agreed that it would not be enforced unless necessary. [122] On August 15, the army officially declared that each camp administration could decide individually whether a curfew was necessary or not. The only restriction was that lights had to be turned out at 10:30 p.m. [123]

The inmates devised a system to manufacture soap from the reclaimed grease of the kitchens. They proudly presented Camp Director Davis with statistics proving that they had saved the army $912 by their ingenious efforts. [124]

The Military Intelligence Service Language School Commandant Colonel Kai Rasmussen, visited Tanforan on Friday, July 31, and Saturday, August 1, interviewing 184 persons. It is from Rasmussen that the interviewees—and as a consequence most inmates—learned that the destination for most of them would be a camp in central Utah. [125]

On June 2 a representative of the sugar beet industry visited Tanforan to speak of the "opportunities offered." Whether it was passive resistance or reluctance to leave their families, only fourteen inmates signed up although payment was slightly higher than the professional rate ($16 per month) at Tanforan. [126]

There were four Caucasian policemen to each 1,000 detainees. Four men were on patrol at any one time, and every point in the camp was covered every half hour. The police also checked all visitors and incoming parcels and were "authorized, without warrant, to enter all buildings and inmate quarters at any time of the day or night. [127]

The post office was located in a barrack near the grandstand. By June, the daily mail volume was 6,600, incoming and outgoing divided equally, plus 500 packages and 40 CODs delivered to the camp.

Chronology

April 28

The camp opens, 421 people arrive.

May 4

Tanforan's library opens.

May 15

First issue of the

Tanforan Totalizer

is published.

May 23

The new camp store opens in the northeastern corner of the grandstand.

May 24

First flag-raising ceremony of World War I veterans held at the southern end of the infield.

May 26

School opens for first-, second-, and third-graders.

May 27

First Town Hall debate.

May 30

Joint open-air Buddhist-Christian Memorial Day Service held.

June 4

School opens for fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders, at Mess Halls 5, 13, and 14, and barrack 104.

June 11

George Aki and Masayoshi Wakai, graduates of the Pacific School of Religion, are ordained as ministers of the Congregational Church.

June 15

High school classes start at mess halls 3, 13, and 19.

June 16

Election of the five-member advisory council.

June 18

Americanization classes for adults begin.

June 22/23

Camp-wide search for contraband.

July 11

First art and hobby exhibit.

July 13, 1943

First barber shop opens.

July 28

Elections for a 38-member inmate "legislative congress" take place.

July 31 and August 1

Representatives from the Military Intelligence Service Language Service School visit Tanforan looking for prospective interpreters for the war in the Pacific.

August 3

Tanforan's elected advisory council and yet uninducted "legislative congress" are dissolved under army orders.

August 10

First full-length movies are shown in the grandstand.

August 16

First wedding in camp.

August 25

State primary elections, with over 500 Nisei voting by mail.

August 28

First basic clothing shipment arrives.

September 5-7

Mardi Gras is celebrated with various sports and cultural events.

September 9

First advance group of 215 leaves Tanforan for Topaz. The center is closed for outside visitors.

September 12

Last issue of the

Tanforan Totalizer

is published.

September 15

Fist regular contingent of 502 leaves the camp for Topaz.

October 1

Last regular contingent of 534 leave for Topaz. 400 remain.

Quotes

First impressions on arrival

"On May 1, 1942, I was given a number and placed in a horse stall at the former Tanforan Race Track, arriving here under armed guards. The Center is surrounded by high barbed wire fence, with a good number of soldiers on patrol outside the fence and internal policemen within."

Miné Okubo, 1942

[128]

On deficiencies in everyday goods

"There are two things in this camp that people want more than anything else – good food and toilet paper. With these two essentials in stock I think that Toni and I are ready to join the ranks of the aristocrats of Tanforan. Thank you very much."

Tamotsu Shibutani, 1942

[129]

On food and medical facilities

"Dear Mr. Roosevelt, The situation at Tanforan becomes increasingly disturbing. We have definite evidence that there is not enough to eat and that the hospital supply is inadequate. [...]. It is so incredible that such a ghastly thing should have happened to American citizens that we are only too ready to believe further outrages. The impossibility of getting any consideration at the gates and the insulting language used by white officials lend wings to rumor. We have a large number of church people at Tanforan [...]. I have been able to see our Japanese priest once in the past three weeks, and then only among a large crowd. The people are bewildered and dazed. [...] We have wired senators and Congressmen, but their reply is to contact the local command. We are afraid of our own military, and have lost faith in their judgement."

Rev. Henry B. Thomas, 1942

[130]

On roll call and teaching at Tanforan

"We get up each morning at 6:45 a.m. There is a head count of all the residents and we must all be in our rooms. After the head count we go to breakfast [...]. I go to work – for me it is teaching in high school. [...] There are 16 classes going on at one time with 16 teachers holding forth without books, without partitions between classes, and without experience, to a group of 500-600 students. I am teaching home economics [...]. I am getting quite inured to trying to outshout all the other teachers, and my throat had adapted itself to constant talking. [...]

Two afternoons a week I teach adult English. I have a class of 12 students, half of whom are alien Japanese and half American citizens who have had their schooling in Japan. The oldest is 65 and the youngest 15. I preach Americanization in all sorts of ways. No flag-waving because I cannot stand that, but I try to make them face the problems of this war [...]."

Marii Kyogoku, 1942

[131]

On Hawaiian culture at Tanforan and evening activities in general

There are lots of interesting things going on practically every night. Wednesday nights are open for Town Hall meetings, with a variety of interesting topics. Thursday nights are for Talent Shows. A couple of weeks ago, under the direction of Mr. G. Suzuki, we put on a Hawaiian program. The orchestra consisted of a steel guitar, two ukuleles, two Spanish guitars, and a vocalist. We also had a male chorus who dressed in hula skirts made of crepe paper, and I did my share by teaching them how to do the hula. We had a large and enthusiastic crowd, and much fun. Saturday nights we have dancing in the social hall, a community-wide affair, with the hall decoratd beautifully with crepe paper or green leaves. Till recently a group of us, so-calles "Jivers" have been having jam sessions in the laundry rooms, but people complained so we wuit that…"

May Mukai, 1942

[132]

On feeling Japanese American

"At first, during the first couple of weeks, I hated myself for being a Japanese but know, after associating with them and learning their language I have no such silly ideas anymore. In fact, I have the idea we should feel proud of our yellow color. As far as this life is concerned, I would give anything to be back at International House with my friends, but on the other hand I would hate to leave my few new Japanese friends that I've made here."

May Mukai, 1942

[133]

Aftermath

By 1950, much of the military construction west of Tanforan was removed although thirteen original acres are still used by the U.S. Marine Reserves. The racetrack burned down on July 31, 1964. In the late 1960s it became the Shops at Tanforan Mall. On September 23, 1991, a plaque was added next to the life-size statue of the famous racing horse Seabiscuit at the southwest entrance of the mall, providing a brief description of the Tanforan Assembly Center. Speaking at the ceremony was Tsuyako Kitashima, an activist from the Redress movement. [134] In 2007, a Garden of Remembrance was planted in honor of the Tanforan inmates.

Finally, in 2022, a $1.4 million Tanforan Memorial was dedicated just outside the San Bruno BART station and the mall. The memorial includes a statue of two Mochida sisters with baggage awaiting the bus for Tanforan, based on the famous Dorothea Lange photograph. The memorial also features a replica horse stall. A newly updated exhibition, "Tanforan Incarceration 1942: Resilience Behind Barbed Wire" also opened inside the BART station. [135]

Alumni

Tamotsu Shibutani, JERS researcher and sociologist

Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima, Civil rights activist

Chiura Obata, Artist and art instructor

Miné Okubo, Painter

Charles Kikuchi, Author and civil rights activist

Fred Korematsu, Plaintiff in the Coram Nobis Cases

Hisako Hibi, Issei painter

Robert Murase, Sansei landscape architect

For More Information

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Tanforan section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16m.htm .

Finney, Ernest J. Words of My Roaring . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Hamamoto, Darrell Y., ed. Blossoms in the Desert: Topaz High School Class of 1945 . San Francisco: Topaz High School Class of 1945, 2003.

Kikuchi, Charles. The Kikuchi Diary: Chronicle from an American Concentration Camp . Edited with introduction by John Modell. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973. Illini Books ed., 1993.

Linke, Konrad. "Dominance, Resistance, and Cooperation in the Tanforan Assembly Center." Amerikastudien/American Studies 54.4 (2009): 627-655. [Linke also has a book manuscript on Tanforan tentatively accepted by the University Press of Colorado. Publication will be in the end of 2021 at the earliest.]

Mizuno, Takeya. "Journalism under Military Guards and Searchlights: Newspaper Censorship at Japanese American Assembly Camps during World War II." Journalism History 29 (2003): 98-106.

National Coalition for Redress/Reparations and Visual Communications. Speak Out For Justice: The Los Angeles Hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Video. National Coalition for Redress/Reparations and Visual Communications, 1988.

Okubo, Mine. Citizen 13660 . 1946. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998.

Second Running. "Historic Tanforan."

Taylor, Sandra C. Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Thomas, Dorothy S., Richard S. Nishimoto. The Spoilage . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946, 1969.

Uchida, Yoshiko, and Joanna Yardley. The Bracelet . New York: Philomel Books, 1993.

Uchida, Yoshiko. Desert Exile. The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family . Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1982.

Wartime Civil Control Administration. Concentration Camp U.S.A. Regulations . July 18, 1942, San Mateo: Japanese American Curriculum Project, 1973.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Footnotes

Much of the research for this article was conducted at the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley in 2006 with a particular focus on the papers of the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS), as that study placed several inmate fieldworkers at Tanforan. Since my visit, many of these records have since been digitized by the Bancroft Library and made available online. In cases where online records can be matched to my original notes, an online citation and link is provided. In cases where the cited document cannot be found among the online records, my original citation—in the format "JERS Reel #, Slide #—is retained.

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 158-60, 184.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet, Tanforan Assembly Center," National Archives II, RG 499, WDC, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 59.

- ↑ Memorandum, Cpt. Jack Blevans (Corps of Engineers), to Col. Karl Bendetsen, June 24, 1942, NA II, RG 499, WDC, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 59, Folder 323.3.

- ↑ "Tanforan Racetrack/Detention Camp," [1980s], Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Tsuyako Kitashima, 2003.123), Densho Digital Repository, accessed on Oct. 20, 2020 at https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-janm-4-22/ .

- ↑ "Fact Sheet, Tanforan Assembly Center."

- ↑ "Minutes of the Executive Council with Mr. Davis," July 22, 1942, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, The Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, Call Number BANC MSS 67/14c, folder B4.10:3, accessed on Oct. 26, 2020 at https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k6dr32wb/?brand=oac4 . Subsequently, this collection will be cited as "JAERDA" with Bancroft call number and weblink. Weekly narrative report, William Lawson to Rex Nicholson, May 13, 1942, Report – Weekly Narrative, Telegrams, Teletypes and Reports, Tanforan Center Manager, Microfilm Reel 266, NARA San Bruno. All subsequent weekly reports from Tanforan Directors Lawson and Davis are on the same reel.

- ↑ Weekly narrative report, Frank Davis to Rex Nicholson, June 4 & June 21(?), 1942.

- ↑ Yoshiko Uchida, Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982), 70; Tamotsu Shibutani, Haruo Najima, Tomiko Shibutani, "The First Month at Tanforan: A Preliminary Report," p. 4, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.31, accessed on Oct. 20, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b023b08_0031.pdf ; Sandra C. Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 65.

- ↑ Miné Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946), 47.

- ↑ Letter, Fred Hoshiyama to Toshi, May 17, 1942, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.41, accessed on Oct. 26, 2020 at https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/28722/bk0013c5k5k/?brand=oac4 ; Weekly narrative report, William Lawson to Rex Nicholson, May 2?, 1942.

- ↑ Fred Hoshiyama, "Population and Composition,", p. 1, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.23, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/28722/bk0013c5h3f/?brand=oac4 ; Weekly narrative report, Frank Davis to Rex Nicholson, May 27, 1942.

- ↑ Ben Iijima Diary, July 12, 1942, JERS Reel 17, Slide 424; Charles Kikuchi, The Kikuchi Diary: Chronicle from an American Concentration Camp , edited by John Modell (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973), 77.

- ↑ Kikuchi, The Kikuchi Diary , 56.

- ↑ U.S. Public Health Service, District No. 5, "Report of Activities in the Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast," June 2, 1942, p. 7, in Roger Daniels, ed., American Concentration Camps: A Documentary History of the Relocation and Incarceration of Japanese Americans, 1942-1945 , Vol. 6 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1989). For information on the health situation in assembly centers in general see Louis Fiset, "Public Health in World War II Assembly Centers for Japanese Americans," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 73 (1999), 565-84.

- ↑ Shibutani, et. al, "First Month," 4; Okubo, Citizen 13660 , 69.

- ↑ Okubo, Citizen 13660 , 98-100; Ben Iijima diary, Aug. 2, 1942, p. 68, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.10 (3/4), http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b024b12_0010_3.pdf ; "Diary B.," Aug. 2, 1942, JERS Reel 16, Slide 209; Tanforan Totalizer , Aug. 1, 1942, p. 2 & Aug. 8, p. 4.

- ↑ Tanforan Totalizer , July 11, 1942, p. 4.

- ↑ Letter, Tom Shibutani to Dorothy Thomas, May 12, 1942, JERS Reel 18, Slide 266.

- ↑ Earl Yusa, "Conditions and Needs at Initial Induction," JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.38, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b023b08_0038.pdf

- ↑ Tanforan Totalizer, Sep. 12, 1942, unpaged.