Resettlement in Chicago

The explosion of Chicago's Nikkei population from just under 400 on the eve of World War II to more than 20,000 by 1946–1947 reflects an extraordinary moment in Japanese American history. Issei and Nisei "resettlers," or participants in the War Relocation Authority's (WRA) ethnic dispersal program, accounted for this rapid and massive influx. The thousands who migrated to the city left the concentration camps cognizant of the federal government's imperative to "assimilate" to the white middle-class. Their responses to this instruction, and to the difficulties of beginning life after incarceration in an unfamiliar place, varied widely from person to person. But ultimately, resettlers collectively challenged the WRA's assimilationist vision and established instead a vibrant—if unexpected—Japanese American community in this Midwestern metropolis.

Chicago's prewar Japanese community differed markedly from its Pacific Coast contemporaries. Unlike those settlements, agricultural laborers did not predominate. Small business owners, service sector workers, and students comprised the local population. Residentially, they scattered throughout the city rather than concentrating in a "Little Tokyo." Early Chicago Japanese also did not encounter the tremendous levels of discrimination that their western counterparts faced. And the city itself was never subject to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 . This crucial exemption—coupled with an acute labor shortage and what the WRA described as a "comparative lack of anti-Oriental feeling"—set the stage for wartime resettlement. [1]

Resettlement's Liberal Vision

Japanese American incarceration entailed a spectacular denial of civil liberties, to be sure. Yet to its administrators—many of whom would be considered liberals in the 1940s—it also presented an unparalleled promise for refashioning ethnic Japanese into model American citizens via state-engineered cultural and structural assimilation. The WRA and its civilian partners imagined post-detention migration throughout the United States—dubbed "resettlement"—as a key means towards this end. The goal, in other words, was for Nikkei to identify and associate fully with mainstream America. As one Chicago-area resettlement coordinator explained, assimilation entailed "the complete incorporation or absorption into our every community social activity where only the difference in physical features are noticeable." [2]

In all, about 36,000 prisoners—or less than one third of the total number—took part in the resettlement program before the end of 1944, starting anew in locations throughout the Midwest, the East Coast, and the mountain states. Of these, 6,599 found their way to Chicago, the most popular destination, with the first few arriving in late 1942. [3] The cosmopolitan city beckoned with its lack of entrenched anti-Asian animus. Most importantly, Chicago offered plentiful and diverse employment prospects. Defense-related industries, especially, sought laborers, and resettlers eagerly applied for positions in munitions factories. Others took service-sector (domestic, restaurant, and hospitality), clerical, or light manufacturing jobs, with many gravitating towards companies willing to take on Nikkei en masse, including Curtiss Candy, McClurg Publishing, Stevens Hotel, and Edgewater Beach Hotel. (Notably, not a few employers preferred Nikkei employees as an alternative to hiring African Americans.) Some even struck out on their own as small business owners and professionals.

Chicago's institutional resources also figured into resettlers' calculus. To expedite resettlement, the WRA opened its first regional field office in Chicago in January 1943. Sixteen other civic and religious agencies also provided assistance with housing, job placement, and personal and social matters. For example, the Church of the Brethren, the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), and the Japanese Mutual Aid Society (founded before World War II) operated hostels for newcomers, while the Advisory Committee for Evacuees, the Chicago Church Federation's United Ministry to Resettlers, YMCAs, YWCAs, the city's parks and recreation centers, and other groups offered recreational opportunities and other services. As news traveled about the earliest resettlers' relatively benign adjustment experiences, a chain migration of friends and family members to Chicago resulted.

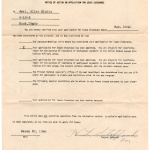

Significantly, the WRA and its partner organizations understood their mission as that of facilitating Japanese American integration, but they placed the onus of assimilation on the Nisei themselves. They emphasized repeatedly that resettlers should "avoid segregation at all costs " and "spread out thinly," joining "Hakujin [white]" groups churches, clubs, and professional associations whenever possible. A number of Nisei took this advice to heart. At least some resettlers truly believed that their every action would affect the overall success of the WRA's assimilationist vision, and they tried in earnest to dissociate themselves—at least in public—from other Japanese Americans. [4]

But most resettlers tested the WRA's guidelines for ethnic dispersal right away. While the WRA and its collaborators ranked assimilation as the topmost priority of Chicago's resettlement program, Nisei (who made up the overwhelming majority of early resettlers) were instead fully preoccupied with day-to-day survival issues during the early months of resettlement in 1943. Most had few, if any, fellow Japanese American co-workers and neighbors. Faced with the hardships of living solo in an unfamiliar city, lonely Nisei readily sought each other out for companionship, preferring the easy company of the other Japanese Americans over the challenges of cultivating relationships outside the ethnic group. This disposition reflected resettlers' hesitancy about interacting with whites, a nervousness that stemmed from their tenuous status in a society still at war with Japan and a painful awareness about the race riots sweeping the country that year.

Racial discrimination also intensified this uneasiness. Despite the absence of restrictive covenants aimed at Japanese, locating satisfactory housing was the single most difficult task for many resettlers. For the most part, they were only able to rent apartments and homes in restricted areas (understood as zones of transition or buffer regions between white and blacks) on the city's Near Northside and Hyde Park-Kenwood on the city's Southside. The dilemma was so widespread that it was documented frequently by the Japanese American press and on occasion by Chicago's mainstream media. In addition to housing, resettlers—like the city's other racial minorities, especially African Americans—encountered racism in the workplace and other public spaces including dance halls, hospitals, and even cemeteries.

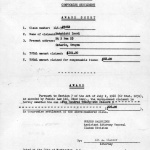

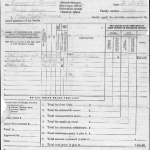

Living an indeterminate present and looking toward an unknown future, countless resettlers readily dismissed resettlement coordinators' behavioral guidelines to act as "ambassadors" to mainstream America and to act in accordance with white, middle-class values of reliability and respectability. This was especially true in regards to employment. As resettlers departed the camps, the WRA had reminded them that leaving their jobs without official government permission "reflected unfavorably" on all Japanese Americans. But resettlers understood that the homefront faced a manpower shortage, and that this scarcity allowed them leverage in the labor market. They continually sought higher paying jobs, and many did not hesitate to breach their current contracts in pursuit of better opportunities, earning them the moniker "60-day Japs." Others quit because they were dissatisfied with their work conditions, including racial discrimination. For many, their insecure status and prospects offset any incentives to find regular work. [5]

Resettlers' social activities also reflected their collective uncertainties and anxieties. They congregated together during their leisure time (all-Nisei dance parties were extremely popular) choosing to "have fun" rather than follow state directives to integrate with middle-class whites and to serve the homefront unfailingly as productive, reliable workers. Drinking, gambling, casual sex, conspicuous consumption, and "loafing" were not uncommon, even as many continued to try to live up to the WRA's expectations. One noted that "most of the Nisei don't feel like working now as it doesn't give them enough time to have fun" after putting in a full day's work. "There's no percentage in that and they feel that they might as well go out and enjoy themselves before the Army takes them... You can't blame some of them for going wild because this is the first chance they have had to have their fling." Another agreed, "A part of the Nisei tendency to be restless and to run around a lot now is the sowing of wild oats." Most of his friends were "more interested in getting larger pay checks and spending the money" on clothes and dancing than in saving their earnings, contributing to the war effort, or creating a favorable impression of Japanese Americans in the ways prescribed by the WRA. As he explained, "They felt that they had been deprived of a lot of things during the time they were in camp and this is a relief to them." Despite federal directives, then, a distinctive Nikkei social world began to coalesce in Chicago immediately after their arrival, endangering the state's blueprint for the rehabilitation of Japanese American citizenship. [6]

Community Formation

Predictably, the Nisei's unseemly habits unsettled resettlement coordinators, who feared they would beget an unfavorable image of Japanese Americans and hinder their full participation in larger society. Fearing that the situation would only worsen over time, a group of Nisei and their allies established the Chicago Resettlers Committee (CRC) in September 1945 "to attend to the unfinished problems of evacuation and resettlement." The formal organization of the Japanese American community was increasingly necessary, they argued, as the WRA and other sponsors began to terminate their support programs at the same moment when the final wave of resettlers arrived in Chicago. The CRC's initial services included assistance with healthcare, business, employment, and housing, and a varied selection of activities to accommodate resettlers' "dramatic" recreational exigencies. While explicitly acknowledging that "the ultimate goal [of resettlement] is for the Japanese Americans to become participating members of the Chicago citizenry," the CRC proposed a radically different approach to resettlement than the WRA. [7] Its leadership maintained that the resettlers' participation in ethnically-exclusive activities rather than predominantly white ones could still be used to achieve Japanese American integration Furthermore, they stressed, the burden of the responsibility for the assimilation and rehabilitation of Japanese American citizenship rested on mainstream institutions rather than on the Nikkei themselves. These arguments sufficiently persuaded the WRA and its partners to reevaluate their original vision for resettlement. Chicago's Council of Social Agencies, the umbrella organization of municipal social services, officially recognized the CRC in September 1946 and agreed to provide half of its operating budget for the coming year.

The CRC's founding and its early years of operation was truly a joint effort among Nisei, Issei, and other prominent advocates for Japanese Americans. By the fall of 1945, the CRC's executive board included representatives from all walks of Chicago's incipient Nikkei community plus a number of non-Japanese civic leaders and business people. Key individuals included Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi , Harry K. Mayeda, Togo Tanaka , Abe Hagiwara, Father Joseph Kitagawa, Tahei Matsunaga, Ryoichi Fujii, Kohachiro Sugimoto, Corky T. Kawasaki, Jack Kaichiro Yasutake, Brother Theophane Walsh, and Horace Cayton. Membership numbers and the activity levels of the CRC skyrocketed in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1954, the CRC formally changed its name to the Japanese American Service Committee, and JASC continues to be a thriving center of Nikkei community life in Chicago to this day.

Thus, with the backing of federal authorities, the city's social welfare establishment, and Issei and Nisei resettlers themselves, Chicago's Japanese American community rapidly organized in the immediate postwar years. In 1946, on the heels of a Memorial Day banquet honoring Nisei veterans, sixteen area institutions formed the Chicago Japanese American Council to oversee general concerns and facilitate communication within and beyond the Nikkei community. During this time, the city was home to several Japanese Christian and Buddhist congregations and related entities, including Japanese Church of Christ, Holiness Japanese Christian Church, the Catholic Youth Organization's Nisei affiliate, the Midwest Shinshu Buddhist Church, the Chicago Buddhist Church, and the Young Buddhists Association. The city saw the emergence of several Japanese-, English-language, and bilingual Nikkei newspapers and magazines, such as the Chicago Shimpo , Chicago Nisei Courier , Scene , and Nisei Vue , as well as an annual yearbook and directory. Well over 100 Nikkei groups sprung up, including hobbyist collectives, kenjinkai (prefectural societies) and teenage girls' clubs (Deborairs, Charmettes, Mademoiselles, Philos, Jolenes, Sorelles, Dawnelles, et al), many of whom were connected through the CRC's City-wide Committee on Recreation (est. 1948). Basketball teams, bowling leagues, and other sports assemblages (Dandies, Saints, Comets, Penguins, Collegians, Robabes, Romans, Lancers, Bruins, and others) developed under the auspices of the Chicago Nisei Athletic Association (est. 1946). Nisei veterans came together as the American Legion Rome-Arno Post No. 1183. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) started both a local chapter and Koenkai (Issei supporters group) in 1945 and a branch of its Anti-Discrimination Committee in 1947. In addition to organizational structures, numerous Nikkei businesses thrived during this period, with an obvious cluster coalescing around the Clark and Division intersection on Chicago's near North side. Gradually, this upsurge slowed with the decline in Chicago's Nikkei population through the 1950s and 60s. Thousands returned to their former homes in the West, while many others sought to make their homes in the city's surrounding suburbs.

Remarkably, then, the sum of resettlers' everyday actions—running counter to federal mandates—impelled authorities to legitimate the constitution of ethnic networks and institutions in the very place where officials had tried to prevent their formation. The growth and spread of Chicago's vivacious Nikkei community during the resettlement period—extending into the present day—vividly captures Japanese America's resiliency after the crisis of incarceration.

For More Information

Albert, Michael Daniel. "Japanese American Communities in Chicago and the Twin Cities. " Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1980.

Briones, Matthew M. Jim and Jap Crow: A Cultural History of 1940s Interracial America . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Brooks, Charlotte. "In the Twilight One Between Black and White: Japanese Resettlement and Community in Chicago, 1942-1954." Journal of American History 86 (March 2000): 1655-1687.

Fujii, Ryoichi. Shikago Nikkeijinshi . Tokyo: Nihon Shuppan Boeki Kabushiki Kaisha, 1968.

Kuzuhara, Dan. "Chicago's Resettlers of the ‘40s." Japanese American Citizens League 29th Biennial National Convention program, 30-33.

Murata, Alice. Japanese Americans in Chicago . Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

Nishi, Setsuko Matsunaga. "Japanese American Achievement in Chicago: A Cultural Response to Degradation." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1963.

Nishi, Setsuko Matsunaga. "Restoration of Commumity in Chicago Resettlement," Japanese American National Museum Quarterly (Winter 1998-99), 2-11.

Osako, Masako. "Japanese Americans: Melting into the All-American Melting Pot." In Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait , eds. Melvin G. Holli and Peter d'A. Jones. Grand Rapids, WI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995, pp. 409-437.

REgenerations: Rebuilding Japanese American Families, Communities, and Civil Rights in the Resettlement Era. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2000. [Chicago volume]

Thomas, Dorothy Swain, with the assistance of Charles Kikuchi and James Sakoda. The Salvage . Berkeley: University of California Press 1952.

Uyeki, Eugene S. "Process and Patterns of Nisei Adjustment to Chicago." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1953.

Wu, Ellen D. The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, WRA: A Story of Human Conservation (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946, 135.

- ↑ Ralph E. Smeltzer, "Present Status of the Community Integration Program in Chicago," typescript, July 9, 1943, box 4, Japanese Relocation Collection, Brethren Archives, Elgin, IL.

- ↑ For population figures for the various resettlement locations, see U.S. Department of the Interior, People in Motion: The Postwar Adjustment of the Evacuated Japanese Americans (Washington, D.C., 1946) and U.S. Department of the Interior, The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington, D.C., 1946).

- ↑ "Evacuee Bulletin to Minister-Counsellors [sic]," Folder "Chicago Church Federation and United Ministry to Resettlers," box 3, Japanese Relocation Collection, Japanese Relocation Collection, Brethren Archives, Elgin, IL; Smeltzer, "Present Status of the Community Integration Program."

- ↑ War Relocation Authority, "When You Leave the Relocation Center," n.d., www.densho.org; S. Frank Miyamoto, "Interim Report of Resettler Adjustments in Chicago," March 1, 1944, reel no. 71, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley; Shibutani, "The First Year of the Resettlement of Nisei in the Chicago Area: A Preliminary Classification of Tentative Plans for Future Research," March 1, 1944, reel no. 72, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

- ↑ Sus Kaminaka (pseudonym), interview by Charles Kikuchi, August 12, 1944, transcript p. 81, box 48, Charles Kikuchi Papers, Young Research Library special collections, University of California, Los Angeles; Dorothy Swaine Thomas, with the assistance of Charles Kikuchi and James Sakoda. The Salvage ( Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), 340.

- ↑ Social Analysis Committee, "Chicago Resettlement 1947: A Report," Chicago Resettlers Committee collection, Chicago History Museum Research Center.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 4:13 p.m..

Media

Media