Community analysts

The community analysts of the

War Relocation Authority

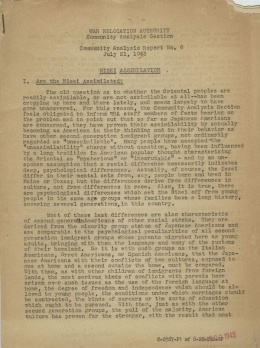

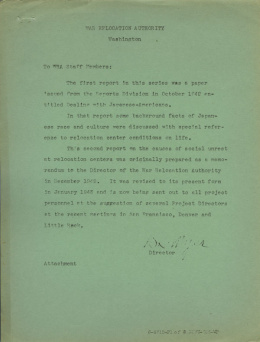

(WRA) provide us with an important window to the lives of Japanese Americans incarcerated in the ten camps. Known as the Community Analysis Section (CAS) of the Community Management Division, these twenty-odd social scientists, nearly all cultural anthropologists, reported on various aspects of the ten WRA camps, unlike their counterparts in the

Bureau of Sociological Research

(BSR) and the

Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study

(JERS) who focused primarily on

Gila River

,

Poston

, and

Tule Lake

. From February 1943, until the camps closed in January 1946, this research team used social science concepts (assimilation, community, education, etc.), oral interviews with key informants, participant observation, and data gleaned from monthly newsletters by the JERS team in the WRA camps to write their Project Analysis, Community Analysts' Notes, Weekly Summaries, and general newsletters.

[1]

CAS Personnel

The CAS had many well-qualified researchers. John Embree , head of the Section, was an expert on Japan, with his study on a rural Japanese village, Suye Mura (1938). Other community analysts too, were already familiar with Japanese Americans, as was Embree with his own study of the Japanese in Kona, Hawai'i. John Rademaker ( Amache (Granada) ) had already written on the Japanese in the Seattle area during the early 1930s, and Forrest LaViolette ( Heart Mountain ) was completing his own monograph of the prewar mainland Japanese community. Others, while new to Japanese Americans, had considerable experience studying American Indians, such as Edward Spicer (Poston), the Opler brothers Morris ( Manzanar ) and Marvin (Tule Lake), and Weston LaBarre ( Topaz ) whose work The Peyote Cult (1938) was widely acclaimed for bringing Freudian psychological analysis to the study of American Indians. Still others, such as Katharine Luomala ( Rohwer ) came to the CAS after work in the Pacific islands, and G. Gordon Brown (Gila River), in East Africa and Samoa. Only a couple of them, such as Rachel Sady ( Jerome ) and John DeYoung ( Minidoka ) were still graduate students. [2]

CAS Accomplishments

Yet the CAS's accomplishments were relatively sparse. They produced few published studies on Japanese Americans compared with the BSR and the JERS research groups. Only Spicer, et. al., Impounded People (1969) made it to press though LaViolette and Rademaker would later publish works on Japanese Americans not involving their wartime incarceration. Federal government censorship restrictions and WRA proprietary ownership of the reports raised a barrier to their publication of studies on Japanese Americans, and hence, they folded their wartime observations on Japanese Americans into their postwar research on topics they believed held wider significance for the social sciences such as "community formation" and "education." Another reason is possibly due to their preoccupation with, and usage of social science concepts such as "community," "assimilation," "education," and "national character studies." For many of them, Japanese Americans were only important to their research as they related to the social science concepts, an approach that contrasted sharply with the JERS group which made the incarcerated population the central focus. Or, they viewed anthropology as apolitical, such as Margaret Lantis who believed her task was to help her subjects deal with "cultural changes" however much she sympathized with them. [3]

But many of them were not indifferent towards the plight of Japanese Americans. In public lectures, John Embree remained staunchly critical of the whole war in general and the mass incarceration in particular. G. Gordon Brown condemned the whole removal and mass incarceration in his reports and after the war, joined Margaret Mead and Elliott Chapple in drafting a code of ethics that demanded applied anthropologists "strive to achieve a greater degree of well-being for the constituent individuals within a social system." Morris Opler researched and wrote the legal brief challenging the entire program of mass removal and confinement before the U.S. Supreme Court. Edward Spicer clearly spoke out against the incarceration in his lectures after the war, as did other CAS researchers. [4]

Contemporary Assessments

But with a few exceptions, the CAS researchers limited their criticism to internal reports and kept silent publicly. This public silence on the immorality of the mass incarceration left them open to harsh criticism in later years. In the 1980s, anthropologist Peter Suzuki, for example, harshly condemned the JERS project as "a disaster of major proportions," after condemning all social scientists in the WRA camps for using "methods, assumptions, and pretensions of conventional American anthropology" that were "found wanting." Historian Francis Feeley accused camp social scientists of propagating "racist theories dressed in the cloak of scientific hypotheses." Orin Starn, then a graduate student in anthropology, chided the camp researchers for having "ignored or dismissed" questions about the morality of the mass incarceration, condemned their positive portrayal of a "happy" rather than miserable incarcerated community, and pronounced them guilty of being "integral contributors" to a discourse that "preempted criticism of removal and legitimized the internment." [5]

Some CAS researchers, however, refused to accept such slander. In particular, Morris Opler and Rachel Sady took exception to Starn, pointing out how federal government censorship laws and a strong public opinion climate backing the Roosevelt Administration precluded open criticism of the mass removal and incarceration program. They also highlighted their own individual efforts at the time to challenge that very program before the U.S. Supreme Court and ameliorate some of the negative conditions in the camps. And they pointed out with some justification the questionable interpretation of some of the writings of CAS researchers that Starn and others employed in their harsh assessment of the camp social scientists. [6]

Regardless of which position one takes, the CAS along with the BSR and JERS researchers bequeathed to future generations many insightful if admittedly biased reports on each of the WRA camps. Used with discernment, historians and other social scientists find these materials important for reconstructing a picture of Japanese Americans under incarceration which has only now begun. [7]

For More Information

Works About CAS Personnel

Bennett, John W. Classic Anthropology: Critical Essays, 1944-1996 . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997.

Feeley, Francis McCollum. America's Concentration Camps during World War II: Social Science and the Japanese American Internment . New Orleans, LA: University Press of the South, 1999.

Hansen, Arthur A. Japanese American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project, Part. III: Analysts . Munich, Germany: K.G. Saur Verlag GmbH, 1994.

Hayashi, Brian Masaru. Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2004.

Ichioka, Yuji, ed. Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study . Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center and the Regents of the University of California, 1987.

Minear, Richard H. "Cross-Cultural Perception and World War II: American Japanists of the 1940s and Their Images of Japan." International Studies Quarterly 24, 4 (1980): 555-580.

Price, David H. Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War . Duke University Press, 2008.

Suzuki, Peter T. "Anthropologists in the Wartime Camps for Japanese Americans: A Documentary Study." Dialectical Anthropology 6 (August 1981): 23-60.

———. "The University of California Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study: A Prolegomenon." Dialectical Anthropology 10 (April 1986): 189-213.

———. "For the Sake of Inter-University Comity: The Attempted Suppression by the University of California of Morton Grodzins' Americans Betrayed ." In Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study , edited by Yuji Ichioka, 95-123. Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center and the Regents of the University of California, 1987.

Works by Former CAS Personnel

Brown, George F. "Return to Gila River." In Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans , edited by Erica Harth, 115-25. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Embree, John F. Suye Mura: A Japanese Village . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1939.

Hansen, Asael T. "My Two Years at Heart Mountain: The Difficult Role of an Applied Anthropologist." In Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress , edited by Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano, 33-37. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1986.

LaBarre, Weston. The Peyote Cult . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1938.

LaViolette, Forrest E. Americans of Japanese Ancestry: A Study of Assimilation in the American Community . Toronto: Canadian Institute of International Affairs, 1945.

Opler, Morris L. "Comment on 'Engineering Internment.'" American Ethnologist 14.2 (May 1987): 383.

Sady, Rachel. "Comment on 'Engineering Internment,'" American Ethnologist 14.3 (Aug. 1987): 560-62 and 15.2 (May 1988): 385.

Spicer, Edward. "Anthropologists and the War Relocation Authority." Applied Anthropology 5 (spring 1946): 16-36.

Spicer, Edward H., Asael T. Hansen, Katharine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler. Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969.

Starn, Orin. "Engineering Internment: Anthropologists and the War Relocation Authority." American Ethnologist 13, 4 (November 1986): 700-720.

———. "Reply to Opler." American Ethnologist 14.2 (May 1987), 383-84.

———. "Reply to Sady." American Ethnologist 14.3 (Aug. 1987): 562-63.

Footnotes

- ↑ Orin Starn, "Engineering Internment: Anthropologists and the War Relocation Authority," American Ethnologist 13, 4 (November 1986): 703.

- ↑ Richard H. Minear, "Cross-Cultural Perception and World War II: American Japanists of the 1940s and Their Images of Japan," International Studies Quarterly 24, 4 (1980): 568-69; Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2004), 20, 213-14; George F. Brown, "Return to Gila River," in Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans , ed. Erica Harth (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 118.

- ↑ Starn, "Engineering Internment," 706-07, 712-15; John W. Bennett, Classic Anthropology: Critical Essays, 1944-1996 (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997), 326.

- ↑ Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy , 19-22; Brown, “Return to Gila River,” 120, 124, 122.

- ↑ Peter T. Suzuki, "For the Sake of Inter-University Comity: The Attempted Suppression by the University of California of Morton Grodzins' Americans Betrayed ," in Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study , ed. Yuji Ichioka (Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center and the Regents of the University of California, 1987), 111-12; Peter T. Suzuki, "Anthropologists in the Wartime Camps for Japanese Americans: A Documentary Study," Dialectical Anthropology 6 (August 1981): 45-46; Francis McCollum Feeley, America's Concentration Camps during World War II: Social Science and the Japanese American Internment (New Orleans, LA: University Press of the South, 1999), 268; Starn, "Engineering Internment," 702.

- ↑ Morris L. Opler, "Comment on 'Engineering Internment,'" American Ethnologist 14, 2 (May 1987): 383; Rachel. Sady, "Comment on 'Engineering Internment,'" American Ethnologist 14, 2 (May 1987): 560-62.

- ↑ Yuji Ichioka, ed., Views from Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center and the Regents of the University of California, 1987), 23, 212-13.

Last updated Dec. 18, 2023, 6:22 p.m..

Media

Media

![[Significant factors in requests for repatriation and expatriation] [Significant factors in requests for repatriation and expatriation]](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/22/55/2255ee2b774ada3c57100c4eec86e84e.jpg)

![[Carp banner (Koinobori) and Boys Day]: Japanese holidays [Carp banner (Koinobori) and Boys Day]: Japanese holidays](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/f1/c0/f1c04a49882476dce6130e14934f3b51.jpg)