Tuna Canyon (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Tuna Canyon Detention Station |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Immigration Detention Station |

| Administrative Agency | Immigration and Naturalization Service |

| Location | Tujunga, California (34.2500 lat, -118.2833 lng) |

| Date Opened | December 16, 1941 |

| Date Closed | October 1, 1943 |

| Population Description | Held Japanese immigrants; also held German and Italian nationals. |

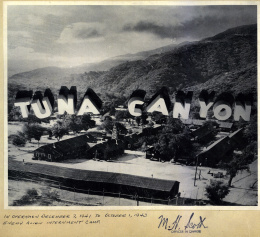

| General Description | Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) detention station located at a former Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp near Pasadena in Los Angeles County, California. |

| Peak Population | |

| National Park Service Info | |

The Tuna Canyon Detention Station was a prison camp that held Issei men from Southern California detained by the FBI shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor . The camp also held local German and Italian internees and Japanese Peruvians . Internees were held there before being transferred to permanent detention camps in other parts of the country. The capacity of the camp was approximately 300. The site—a former CCC camp that later became part of the Verdugo Hills golf course—is currently slated for residential development.

Site Background

For hundreds of years the Tongva-Gabrielinos inhabited the village of Tujunga, thriving in one of the oldest villages in Southern California. The first Europeans to explore this area were Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo and Gaspar de Portola. Father Junipero Serra established two of the first nine missions near Tujunga with the help of the Portola expedition: the San Fernando and San Gabriel missions. A Mexican land grant was given to two brothers, Francisco and Pedro Lopez, and they called it Rancho Tujunga, engaging in agriculture and cattle ranching. When gold was first discovered in 1842 on the Rancho Tujunga, it brought a wave of prospectors, loggers, settlers, and outlaws to the area. [1]

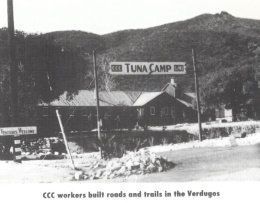

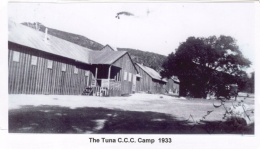

A Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp named La Tuna Camp opened in May of 1933 located at 6330 Tujunga Canyon Blvd. in Tujunga about fourteen miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles and six miles north of Glendale. The CCC camp was taken over by the U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service on December 8, 1941, for the purpose of detaining and identification of enemy aliens. The official government name of the camp was "Tuna Canyon Detention Station, Immigration and Naturalization Service"; M. H. Scott was assigned to be the officer-in-charge. [2]

Department of Justice Detention Camp

Tuna Canyon Detention Station received its first enemy aliens who had been taken into custody by the FBI on December 16, 1941, and thereafter operated as a clearing-house for the male Japanese enemy aliens arrested in Southern California. From that date until May 25, 1942, 1,490 Japanese males passed through the camp and were transferred to other camps in Fort Missoula , Montana, Fort Lincoln , North Dakota, and Santa Fe , New Mexico. [3] According to a report submitted after a visit by the Spanish consul, there 76 Japanese males held at the camp on May 28, 1942. [4] The population was diverse in Tuna Canyon Detention Station: there were Japanese, Germans, Italians, and later, Japanese Peruvians, with the latter being sent to Kenedy INS detention camp in Texas. Tuna Canyon and Sharp Park detention stations held the largest number of Japanese internees. [5] Herbert Nicholson , a frequent visitor to the camp, stated, "When they would get three hundred men they would ship them out a whole trainload of them up to some other place. Missoula had six hundred then they sent additional ones out to Bismarck, North Dakota." [6] According to Tetsuden Kashima some Issei stayed for various lengths of time from a few weeks to three months, before boarding a train with blackout shades for the long ride to Fort Missoula, Montana or Fort Lincoln, North Dakota. [7] George Tsumori a resident of Tujunga owned three produce stands in the area. While working at his produce business he was helping the FBI as an interpreter at the Tuna Canyon Detention Station and had to be on call at all hours. [8]

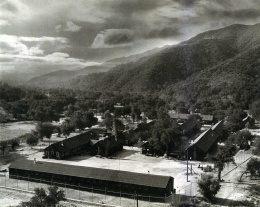

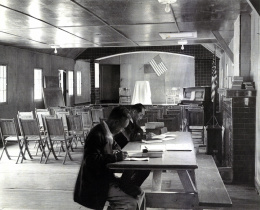

In a memorandum from Officer-in-Charge Scott, the camp included seven barracks, an infirmary, a mess hall, and office buildings and could hold 300 persons. There was medical care, a barbershop, and a canteen that sold sundries and other items at wholesale prices to the internees. Religious services were conducted by visiting religious leaders, but also there were several Christian ministers and two Buddhist priests interned at the station who also conducted services. Visitors were allowed, but because there were 1,837 visitors on one Sunday, visiting times for each member of the family were subsequently limited to two minutes each. Scott initiated a self-government honor system among the detainees, allowing them to elect barrack captains and a mayor of the station. The internee leaders would take over the affairs of the detainees such as designating the cooks, kitchen police, orderlies, and wood burning stove maintenance workers. Mail such as letters, postcards, and telegrams in English or their native language was subject to censorship. Internees could receive food and clothing from family and friends; some 5,000 packages were received for the 160 day period. [9]

Herbert Nicholson, a Quaker missionary and friend of Japanese Americans, was one of the earlier visitors to Tuna Canyon and other internment camps. He would report to the internees and to the worried families how each was doing; many were his friends from Terminal Island . During his visits, he would aid Issei internees as an interpreter and a character witness at their hearings since he was fluent in Japanese. He also thought that M.H. Scott was kind and sympathetic to the Japanese internees. Because of Scott's compassionate treatment of the Issei men interned at Tuna Canyon Detention Station there are letters of gratitude on file at the National Archives. [10]

On May 28, 1942, Francisco de Amat, the Spanish Consul at San Francisco, visited the camp. (As a neutral party, Spain represented the interests of the Japanese.) In a report filed by Bernard Gufler, assistant chief of the Special Division, Department of State, the internees lodged a number of requests and observations. Interviewed by the representatives of the protecting power alone then as in a separate interview in the presence of the representatives of Department of State and Justice, they stated they had no complaints with regards to the detention camp or treatment. They especially requested that the representatives of the protecting power convey to the Japanese diplomats interned in a hotel for Japanese government officials (the Greenbrier Hotel) in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, that they were being treated well and requested good treatment of the Americans in Japanese hands. The internees also requested a male nurse. They did complain about the slowness of action on their hearings, expressing a desire that speedier action be taken in communicating decisions to release or parole in order that they might join their families in assembly centers. The second complaint was that some Korean interpreters employed by the FBI had not interpreted their answers to questions fairly or correctly and had endeavored to trick them and to deceive the American officers interrogating them. The report also described the camp as being located in a former CCC camp in an attractively wooded valley with lots of shade. [11]

One of the most notable internees held at Tuna Canyon was Toraichi Kono, Charlie Chaplin's chauffeur and personal secretary until 1934. Kono was picked up before and after the attack of Pearl Harbor and was accused of being a spy for the Japanese military. On his second arrest he was sent to Tuna Canyon Detention Station on December 19, 1941, as was subsequently transferred to detention camps in Fort Missoula, Santa Fe twice, and Kooskia , before finally being reunited with his family at Crystal City . Kono worked in Little Tokyo after the war to help attorneys Wayne Collins and Tetsujiro "Tex" Nakamura on many Nisei and Kibei renunciant cases. Kono went back to Japan to live and continued to assist Wayne Collins with restoring U.S. citizenship to the Nisei and Kibei who had renounced and were stranded in Japan. [12]

According to Scott, the end date of operations of the camp was October 1, 1943. [13]

Aftermath

After the war, the former CCC camp and Tuna Canyon Detention Station became an L.A. County probation school for boys. In 1960 a group of doctors purchased the land and built the Verdugo Hills Golf Course. Though the course is still operating today, the property has been sold to a developer who will be building homes. Tuna Canyon Detention Camp and the former CCC camp were located in the southeastern area of the golf course, where the driving range and overflow parking are located. [14]

After many years of hard work, Little Landers Historical Society, with the leadership of Lloyd Hitt, Mike Lawler, and former Los Angeles City Councilman Richard Alarcon, the Tuna Canyon Detention Station's site was finally designated a historic site by the City of Los Angeles. The newest update has been a setback for the Tuna Canyon Detention Station preservation advocates because the developer has initiated a lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles alleging illegal historic-cultural monument status. [15]

For More Information

Marlene A. Hitt, and Little Landers Historical Society. Sunland and Tujunga: From Village to City . Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Yamamoto, J.K. "Commission Votes Against Landmark Status for Tuna Canyon." Rafu Shimpo , April 29, 2013. http://www.rafu.com/2013/04/commission-votes-against-landmark-status-for-tuna-canyon

Footnotes

- ↑ Marlene A. Hitt, and Little Landers Historical Society, Sunland and Tujunga: From Village to City (Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing, 2002) 9–14.

- ↑ Memorandum Report to W.F. Kelly, Chief Supervisor, United States Border Patrol from M.H. Scott, Officer in charge of Tuna Canyon Detention Station, 5 pages and dated May 25, 1942, p 1. Document copied by Lloyd Hitt and Paul Tsuneishi of the Little Landers Historical Society, http://www.littlelandershistoricalsociety.org/ , at the National Archives in Laguna Niguel, CA and a copy was donated by Mike Lawler to the Hirasaki National Resource Center.

- ↑ Memorandum Report from M.H. Scott to W.F. Kelly, May 25, 1942, p. 1.

- ↑ Confidential Report On Civilian Detention Camp Tuna Canyon, Tujunga, California, Near Los Angeles, California, May 28, 1942 by Bernard Gufler, Assistant Chief, of the Special Division, Department of State, concerning the visit of the Spanish Consul Francisco de Amat accompanied by M.F. Kelly, Chief Supervisor Border Patrol, copied at the Laguna Niguel National Archives by Lloyd Hitt and Paul Tsuneishi of Little Landers Historical Society, Records RG 59, General Record of State Department, Special War Problems.

- ↑ Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 107 and 253n11.

- ↑ "A Friend of the American Way: An Interview with Herbert V. Nicholson," in Voices Long Silent: An Oral Inquiry into the Japanese American Evacuation , edited by Arthur A. Hansen and Betty E. Mitson (Japanese American Project, The Oral History Program California State University, Fullerton, 1974), 124–26.

- ↑ Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 3.

- ↑ Hitt, Sunland and Tujunga , 147.

- ↑ Memorandum Report from M.H. Scott to W.F. Kelly, May 25, 1942, pp. 1 and 3.

- ↑ "A Friend of the American Way: An Interview with Herbert V. Nicholson"; Priscilla Wegars, Imprisoned in Paradise: Japanese Internee Road Workers at the World War II Kooskia Internment Camp (Moscow, ID: Asian American Comparative Collection, 2010). According to Wegars, Scott became the superintendent of the Kooskia Internment Camp in December 1943 after Tuna Canyon closed, staying until around March of 1945.

- ↑ Confidential Report On Civilian Detention Camp Tuna Canyon, Tujunga, California, Near Los Angeles, California, May 28, 1942 by Bernard Gufler.

- ↑ "Toraichi Kono: A Profile," from the website of a forthcoming documentary film titled Living in Silence: Toraichi Kono , directed by Philip W. Chung and produced by Clyde Kusatsu, Tim Lounibos, and Nancy Yuen, http://www.konofilm.com/ >

- ↑ Merrill Scott’s photo album of Tuna Canyon Detention Station courtesy of David Scott and family.

- ↑ Information provided by Mike Lawler president of the Historical Society of Crescenta Valley from articles he has written about Tuna Canyon Detention Station and the future of a historical marker. See also http://www.cvhistory.org/ .

- ↑ For updates on historical recognition of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station, see the Little Landers Historical Society website at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Tuna-Canyon-Detention-Station/356878631079498 ; Gann Matsuda, "Historic Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition Responds To Developer’s Lawsuit Against City, Details Mission, Goals, Vision For Monument," Manzanar Committee blog, August 13, 2013, viewed on October 14, 2013 at http://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2013/08/13/historic-tuna-canyon-detention-station-coalition-details-mission-goals-vision-for-monument/ ; "City Council Unanimously Declares Grove at Tuna Canyon Site a Historic-Cultural Monument," Rafu Shimpo , Jun3 26, 2013, viewed on October 14, 2013 at http://www.rafu.com/2013/06/city-council-unanimously-declares-grove-at-tuna-canyon-site-a-historic-cultural-monument/ ; and "Tuna Canyon Detention Station Important Update," Glendale Crescenta Voice , August 15, 2013, viewed on October 14, 2013 at http://www.gcvoice.org/current-projects/vhgc.htm .

Last updated Dec. 19, 2023, 4:44 a.m..

Media

Media