Wayne M. Collins

| Name | Wayne Collins |

|---|---|

| Born | November 23 1899 |

| Died | July 16 1974 |

| Birth Location | Sacramento, California |

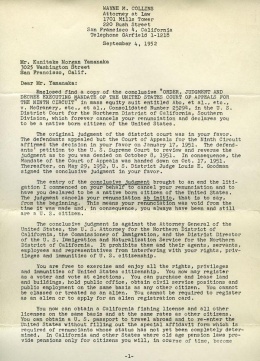

San Francisco-based lawyer who dedicated much of his career to defending Japanese Americans affected by the events of World War II, particularly unpopular cases that others avoided. In addition to representing Fred Korematsu and arguing his and Mitsuye Endo's cases before the Supreme Court, Wayne Mortimer Collins (1899–1974) also defended Japanese Latin Americans , represented accused traitor "Tokyo Rose" Iva Toguri d'Aquino , and most significantly, aided some 5,000 Nisei who renounced their American citizenship during World War II.

Of Irish descent, Collins was born in Sacramento, California on November 23, 1899, and was a graduate of San Francisco Law School, where he was a classmate of future California Governor Edmund G. Brown. During the prewar years, he was affiliated with the Northern California office of the American Civil Liberties Union (NC-ACLU), which was run by his friend Ernest Besig , and maintained a small private practice in San Francisco. Collins was not notably successful during these years. Virtually all accounts of his career, even admiring ones, call him some variation of the adjective "fiery" and note his temper, which could be a major handicap in attracting clients and persuading judges and juries.

Wartime Cases

In 1942, Besig recruited Collins to represent Fred Korematsu on behalf of the NC-ACLU. Korematsu, a young Nisei man, had evaded the exclusion orders, and the NC-ACLU took up his defense as a test case of the orders. During preparations for the trial, the national ACLU office adopted a policy of not directly challenging the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 , which Collins' legal arguments in favor of Korematsu immediately violated. This dispute between the Northern California office and the national organization would continue through the war. Collins argued the case before Judge Adolphus F. St. Sure, who found Korematsu guilty and sentenced him to five years probation (St. Sure initially refused to issue a final order, which led to a round of appeals over whether the case could be appealed).

During 1943-44, Collins represented Korematsu in his appeals, first to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and ultimately before the Supreme Court. He was also invited by James Purcell to argue before the high court in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo (1944) , an appeal arising from the habeas corpus petition of Mitsuye Endo. During the argument before the U.S. Supreme Court, Collins distinguished himself by his rhetorical thrusts. For example, he deplored the military's mass exclusion of Japanese Americans by asserting "The only act resembling this was committed by Adolf Hitler, who penalized German citizens on the basis of their nationality." [1]

Assessments of his wide-ranging and angry arguments are decidedly critical. Peter Irons calls Collins' Korematsu brief "short on analysis and long on vituperation" and "a disaster," while Roger Daniels wrote of his oral argument for Korematsu, "those attuned to the nuances of appellate rhetoric would wring their hands and roll their eyes when discussing his performance." Still, in summing up Collins's overall contribution, Neil Gotanda remarked that, "Whatever may have been his eccentricities as a litigator, his energy and perseverance were extraordinary...." [2] In fact, Collins took on the entire financial burden of the cases himself. In addition to the billable hours he devoted to the defense of Korematsu, he paid for his own extensive travel, including a pair of trips to Washington DC. Thus, according to his friend Ernest Besig , Collins's total contribution to the case exceeded $10,000.

In addition to arguing the Korematsu and Endo cases before the Supreme Court, Collins also filed amicus briefs for the NC-ACLU in the [[Hirabayashi v. United States| Hirabayashi and Endo Supreme Court cases (the latter despite also being one of Endo's attorneys). Collins also submitted an amicus brief for the NC-ACLU in Regan v. King (1943), the challenge brought by the Native Sons of the Golden West to Nisei voting and citizenship rights.

Renunciation Cases

Collins's greatest effort on behalf of the Japanese American community no doubt came in his herculean twenty plus year battle on behalf of the renunciants, the Nisei who renounced their American citizenship, most of them while incarcerated at Tule Lake . As historian Donald Collins (no relation) wrote, the extraordinary demands of these cases against a recalcitrant Department of Justice made Wayne Collins's a virtual "one-case office." He remarked that he didn't even take vacations, because "I was frightened stiff that if I was not able to be in my office every day early and late that the government might attempt to remove all of them to Japan." [3]

He first learned of the renunciation crisis while visiting Tule Lake in July 1945 on other business. Initially incredulous at the situation, he was soon approached by renunciants and their parents asking for help in canceling the renunciations. He initially wrote a letter of protest to Attorney General Tom Clark and prepared form letters for the renunciants asking for the restoration of their citizenship to be sent to the Justice Department. Although he encouraged them to find attorneys, the search for attorneys who would represent them proved largely fruitless, apart from A.L. Wirin , Collins's rival. By September 1945, about 1,000 renunciants had banded together to form the Tule Lake Defense Committee , and the group approached Collins to represent them.

What followed was a bewildering legal odyssey. Collins' first task was to prevent the imminent deportation of the renunciants, announced in October. Collins filed mass habeas corpus suits on behalf of 935 plaintiffs on November 13, 1945, just two days before the deportations were to begin. The lawsuits halted the deportations. As a result of the suits, the Department of Interior instigated a series of "mitigation" hearings that, while of questionable fairness, did result in the release of 90% of the over 3,000 individuals who received them. This still left some 350 detained. After much legal wrangling, Collins was able to get this last group released by Judge Louis Goodman in September of 1947. The case was later reversed on appeal, and eventually mooted by the U.S.-Japan peace treaty signed in 1952, which ended any threat of deportation. Collins terminated the suits in May 1952.

Though freed, the renunciants were still denied their U.S. citizenship. In parallel suits filed at the same time as the habeas corpus suits, Collins sought to invalidate the renunciations. His core argument was that the renunciations were not made freely due to conditions created by actions of the federal government. In March of 1949, Judge Louis Goodman ruled in the renunciants' favor, restoring citizenship to all and refusing the Justice Department's petition to hold individual hearings to make a case-by-case determination. (Though the suit had begun with fewer than 1,000 plaintiffs, it had grown to a total of 4,394 Nisei as more and more renunciants had joined over the years.) This ruling, however, was overturned on appeal in January 1951, due in part to a prior ruling on a suit filed individually on behalf of three renunciants by A.L. Wirin. While ruling the restoration of citizenship valid for about 1,000—mostly those who had been under twenty-one when they renounced—the appellate ruling returned some 3,000 others to the District Court for individual hearings. Though Collins was able to reach an agreement with DoJ lawyers for a process involving affidavits by the renunciants, the process still took nearly all his time, as the DoJ continued to fight many cases. Collins would end up filing some 10,000 affidavits. A "liberalized" process announced in August 1956 led to the resolution of most cases by 1959. However, some 300 remained, requiring another nine years of Collins's effort before the last case was cleared in 1968. In the end, Collins' work insured that not one renunciant was deported once he began representing them, and nearly all who sought the restoration of citizenship got it eventually.

Other Cases and Legacy

Collins had first visited Tule Lake in August 1944, using the threat of habeas corpus suits to get the infamous stockade closed down. A year later, when the stockade had been reestablished, he went back to the camp and once again had it closed down, this time for good.

In the midst of the renunciation drama, Collins took on two other unpopular Japanese American cases. While working on renunciation cases with colleague Theodore Tamba at Crystal City , he was approached by a group of Japanese Latin Americans who had been notified of their imminent deportation. He agreed to represent them, taking as his fee only what they could pay; in many cases this meant pro bono work or being paid in kind (in one case, with chickens). He filed suit on behalf of some 350 Latin American Japanese men, women and children to stop their deportations in June 1946. In the end, Collins was able to secure their release from detention, many being released to work at Seabrook Farms in New Jersey. Collins and Tamba worked on the cases for nearly a decade, with most of those whom they represented ultimately being allowed to stay in the U.S.

Finally, Collins, along with Tamba and George Olshausen, represented Iva Toguri D'Aquino in the famous "Tokyo Rose" case. Toguri, a Nisei women trapped in Japan after Pearl Harbor , was tried for treason for making English-language radio broadcasts during the war. Collins represented Toguri without fee through her trial. Following a trial marked by irregularities and doubtful conduct by the prosecutors and by presiding judge Michael Roche, she was convicted and sentenced to a ten-year prison sentence and fine. Collins and others continued to represent her through a series of unsuccessful appeals in the 1950s. When she was released from prison in 1956, and threatened with deportation, Collins again defended her, and got the deportation order reversed. Toguri ultimately lived with the Collins family for nearly two years. He supported the movement for a pardon, though he died before the pardon was granted by President Gerald Ford in 1977.

Collins's dogged pursuit of justice for the most unpopular Japanese Americans has made him a heroic figure to many. No fewer than four books are dedicated to him, including Michi Weglyn's landmark Years of Infamy . Two men who were among the renunciants he defended also dedicated their memoirs to him, with playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi writing that he "rescued me as an American and restored my faith in America," and Minoru Kiyota calling him "a figure that shines brilliantly in the history of the defense of human rights." Still, his rough edges irked even friends and supporters. In an otherwise admiring description of him written during his lifetime, Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis conclude that "Some of his clients called him a 'brave man'; others, including Nisei, said that he was 'a fanatic' and 'a lunatic.'" [4]

Collins died on an airplane en route to Honolulu on July 16, 1974, just as attitudes toward the Japanese American wartime experience—and particularly the unpopular Japanese Americans he represented—were beginning to change.

For More Information

Christgau, John. "Collins Versus the World: The Fight to Restore Citizenship to Japanese American Renunciants of World War II." Pacific Historical Review 44.1 (Feb. 1985): 1-31. Reprinted in The Mass Internment of Japanese Americans and the Quest for Legal Redress . Asian Americans and the Law: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Vol. 3. Edited by Charles McClain. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1994. 345–75.

Collins, Donald E. Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II . Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Gotanda, Neil. "'Other Non-Whites' in American Legal History: A Review Essay on Justice at War ." Journal of Gender, Race & Justice 13 (2009–10): 333–70.

" Guide to the Wayne M. Collins Papers, 1918–1974 (bulk 1945–1960) ." The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Kashiwagi, Hiroshi. "Wayne M. Collins." In Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings . San Mateo, Calif.: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2005. 176–84.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Footnotes

- ↑ Warren B. Francis, "Jap Exclusion Argued Before Supreme Court," Los Angeles Times , Oct. 12, 1944, 2.

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 303; Roger Daniels, The Japanese American Cases: The Rule of Law in Time of War (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2013), 69; Neil Gotanda, "'Other Non-Whites' in American Legal History: A Review Essay on Justice at War," Journal of Gender, Race & Justice 13 (2009–10), 345n71.

- ↑ Donald E. Collins, Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985), 133, 111.

- ↑ Hiroshi Kashiwagi, "Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings" (San Mateo, Calif.: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2005), i; Minoru Kiyota, Beyond Loyalty: The Story of a Kibei (Honolulu : University of Hawai'i Press, 1997), 132; Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans during World War II (Toronto: Macmillan, 1969), 447.

Last updated Dec. 16, 2023, 11:57 p.m..

Media

Media