Santa Anita (detention facility)

This page is an update of the original Densho Encyclopedia article authored by Konrad Linke. See the shorter legacy version here .

| US Gov Name | Santa Anita Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Arcadia, California (34.1333 lat, -118.0333 lng) |

| Date Opened | March 27, 1942 |

| Date Closed | October 27, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Clara Counties, California. |

| General Description | Located at the Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, California. |

| Peak Population | 18,719 (1942-08-23) |

| Exit Destination | Poston, Topaz, Gila River, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Rohwer, Granada, and Manzanar |

| National Park Service Info | |

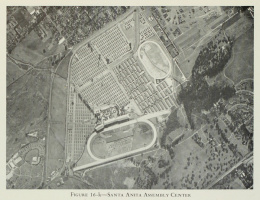

Located at the Santa Anita Racetrack in the city of Arcadia, approximately thirteen miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles and twenty miles west of the Pomona Assembly Center , Santa Anita was occupied from March 27 until October 27, 1942, a total of 215 days. Santa Anita was the largest and the longest-occupied of the temporary WCCA camps. Its peak population was 18,719. Over 8,500 Japanese Americans lived in converted horse stalls at the racetrack. It was the only WCCA camp to run a camouflage net factory , operated under military contract. The majority of Santa Anita's inmates were eventually transferred to Heart Mountain , Rohwer , Amache , and Jerome . [1]

Site History/Layout/Facilities

Site History

The area was originally part of "Rancho Santa Anita," owned by the San Gabriel Mission Mayor-Domo. The ranch was acquired by gold prospector Elias Jackson "Lucky" Baldwin, and in 1904, he built the first racetrack adjacent to the present site. Named "Santa Anita Park," it closed in 1909 and was reopened on Christmas Day 1934 after California again legalized betting. Today Santa Anita Park is the oldest racetrack in Southern California.

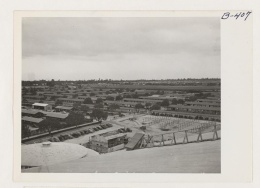

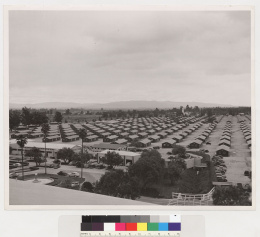

The WCCA leased the site from the park operators in mid-March 1942. Construction to convert the racetrack into a temporary concentration camp was started on March 20. Army engineers renovated the stable area and added 582 barracks, measuring 20 x 64 feet, in the former parking lot. The total cost of construction up to May 25 was $2,785,650, approximately $145 per inmate.

Layout and Housing

Spread over 420 acres, inmates at Santa Anita were held both in barracks and in horse stalls converted to living quarters. 8,500 of the total population of over 18,000 lived in stables. [2] A former student from Berkeley wrote to friends of her impressions: "We are fenced in on one hundred acres of sand and gravel, with monotonous rows upon rows of black barracks and green stables. There is little individuality either in our living quarters, or manner of living [...]." [3]

The camp was divided into seven districts, with districts 1–3 comprising the stable areas and districts 4–7 comprising the areas with newly constructed barracks. Bachelors were housed in the grandstand building. The camp was surrounded by a high barbed wire fence and several tall guard towers. Two military police companies, consisting of about 200 soldiers, were stationed at the southern corner of the camp and guarded the perimeter.

About 520 of the 582 newly constructed barracks were used as living quarters and originally subdivided into three apartments. Although barracks were finished by the end of April, the army engineers had to return in May to further divide the barracks into six-room units: two 8 x 20 feet units to house families of two or three, and four 12 x 20 feet units for families of four to six. The partitioning was completed on May 20. Before partitioning, an average of thirteen Japanese Americans were housed in each barrack; after the partitioning the average was slightly more than twenty-eight. At the beginning of May, the camp director still assumed that the camp would have to hold 21,000, but due to some last-minute shuffling the influx was stopped after about 18,500 inductions. [4]

Cots were the only furniture provided by the army, one to a person. In May there were 15,000 mattresses available; latecomers thus received merely mattress covers for straw bed sacks. In addition, each unit was provided with a bucket and a broom. Cooking in the barracks was forbidden due to the danger of fuses blowing out. Special permission to retain hotplates were issued to families with children under ten years of age or elderly people requiring special diets until a special diet kitchen was put in operation on June 15.

Within weeks fruit crates discarded from the mess halls and leftover lumber were converted by inmates into dressers and tables, shelves and chairs. In the stable area, where the soil was rich, vegetable and flower gardens sprang up everywhere. In the parking lot area, inmates resorted to growing plants in large cans discarded by mess halls. Most of the vegetables grown could be easily converted into tsukemono (Japanese-style pickles), such as napa (Chinese cabbage), daikon (Japanese radish), cucumber and red radish. [5]

Bath and Laundry Facilities

Sanitary facilities were inadequate and overcrowded. In his report from May 11, the camp director reported that the main problem was the "lack of adequate shower and laundry facilities." Until the beginning of July, for example, there were only 150 showers available for over 18,000 detainees. Six new shower buildings (20 x 28 feet) with 75 shower heads each brought the shower-inmate ratio to 1:30, still well below the average ratio in WCCA camps of 1:22. [6] Showers were open from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. and had one section for women and one for men. The women's section had eight rooms with five shower heads each and the men's section seven rooms with five shower heads. For the bathing of infants, hot water could be obtained from the rear of the mess halls at any time of the day. Chlorine footbaths were provided at the entry of the shower booths, but as in other camps, most people preferred to wear self-made wooden clogs, or geta . [7]

During the first two months, there was only one laundry unit operating. It had space for 100 tubs and two ironing rooms with 100 boards to satisfy the needs of over 18,000 people. Because the laundry building was quite far from most of the barracks, some inmates constructed some sort of wheeled vehicle while others ordered Sears Roebuck kiddie wagons to transport the laundry to and from the washing rooms. On July 29, a laundry and dry cleaning service (Harbor Laundry Co. Inc.) was contracted to take orders from the inmates. [8]

On April 15, the camp's post office opened a letter by Kujo Saki addressed to a Caucasian friend, in which she complained about the living conditions. The alarming letter was forwarded to the chief of the Assembly Center Division and caused him to personally visit the camp on April 22. Rex Nicholson concluded, however, that "living conditions [...] are as good as could possibly be expected under the circumstances", and that "strong recreational programs [will] alleviate any present reason for complaint, which are mainly idleness." [9]

A problem unique to Santa Anita was the sewage situation. Sewage flowed through open ditches in the camp that regularly clogged, resulting in obnoxious odors in many parts of the camp. By mid-July, thirty to forty 1,000 gallon tanks of sludge were being removed each day from cesspools and ditches. [10] On July 23, the United States Engineering Department started building an additional 35 cesspools. Work was finally completed on August 21, five days before the first Japanese Americans were moved out of Santa Anita. [11]

Mess Halls and Feeding

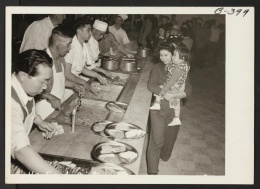

There were six mess halls, named by color: 1-blue, 2-red, 3-green, 4-white, 5-orange, and 6-yellow. On April 3, the blue mess, located in the stable area, opened, providing seating for 850 people and serving almost 3,000 people daily. [12] It also had a separate room reserved for the Caucasian staff who were charged 25¢ per meal. [13] The Red Mess, located under the grandstand, opened shortly after. The Green Mess was located in the parking lot area and opened on April 29. [14] Breakfast was served from 6:30 to 7:30, lunch from 11:30 to 12:30, and supper from 4:30 to 5:30. Each mess hall served about three times the number of people it had seating capacity for, sometimes more. Thus people had to eat in three shifts, and as there were just enough dishes for one shift, all the dishes had to be washed in-between the shifts, making the already strenuous job of the dishwashers even harder. On July 1, the White Mess adopted a new ticket system that reduced waiting times from thirty minutes to ten minutes on average. After a successful trial the system was adopted at all mess halls by July 18. [15]

During the first week "B-rations" were served—food from cans and dehydrated meals that needed no cooking facilities. Tamie Tsuchiyama , writing up her experiences for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS), observed:

Menus on paper do not convey the quality of food [...] actually served. String beans on paper, for instance, connotes to me young and tender beans still retaining its greenish color after cooking – and not the brownish mashed affair they refer to as stringed beans. Likewise, macaroni and cheese, as it appeared on the table during our initiation period, reminded me of half a cup of maggots immersed in a pint of dish water. [16]

Even the optimistic camp newspaper, the Santa Anita Pacemaker , conceded that "limited seating capacity and a lack of equipment" caused serious problems. An inmate wrote: "If one sits near the section where the plates are being washed one cannot hear oneself speak, the noise is so stupendous. [...] We climb in and out of benches to eat. We have one tin plate, one tin cup, and usually one or two silver pieces. Though the food is good, the surroundings make it less savory, and the environment is especially hard on children." [17]

The average budget for feeding one inmate in WCCA camps was 39 cents daily. The average costs of rations per evacuee at Santa Anita were as follows [18] :

| April | May | June | July | August | September | October |

| .22 | .30 | .41 | .42 | .45 | .41 | .42 |

Following massive and ongoing complaints of poor quality and insufficient quantity, Fourth Army officers investigated the conditions on May 24, staying two days, and submitting a list of suggestions, including raising the amount of rice from 20 lbs. to 33 lbs. per 100 people and setting up Mess Hall 4 for family feeding. To achieve the latter, Major Condon immediately ordered chinaware from the San Francisco office despite concerns by Santa Anita's chief steward that this would raise costs and that the WCCA might deem this too much of a treat for the inmates. [19] However, the Fourth Army officers prevailed. Camp Director Russell Amory reported on June 2 that costs were now one-third higher than cafeteria-style feeding, that the rate was 4,000 rations for 3,200 persons (more food per person), but at the same time there was "very little garbage and practically no waste". Also, almost no chinaware was broken. [20] After the successful test phase, the family-style cafeteria, complete with chinaware, was officially inaugurated at the end of June at Mess Hall 4. [21] The family-style feeding, with food being served on the tables, proved so popular that the inmate food committee devised a "hybrid" system for the other mess halls, in which the main course was served cafeteria-style while side dishes such as vegetables, rice, and salad, and soup, were placed in bowls on the table. This solution was eventually installed at all mess halls. [22] An important catalyst for improvement of food was the camouflage net workers strike of June 16 (see Santa Anita Camouflage Net Factory article) after which, according to Tamie Tsuchiyama, "the food improved tremendously not only in quality but in quantity." [23] While the costs of the daily food ration rose to 41 cents in June, the protests about the food situation significantly abated. [24]

On June 15, a special mess line was started in each mess hall for children up to twelve years of age, at which they received a stalk of celery, an orange or an apple, and half a pint of milk in addition to the regular meal. For infants up to two years of age there were 27 milk stations distributed over the camp, supplied with cereal, vegetables, milk, orange juice and infant formulae. Mess No. 4 also contained a special diet kitchen at the rear for people with diabetes, hypertension, allergies. Mess No. 3 served a vegetarian diet for Seventh Day Adventists. [25]

To encourage cleanliness in the mess halls a rating system was introduced, similar to the one in Tanforan and other camps; each week the winner was allowed to hoist an "E"-banner (for excellence) at its mess hall.

There were two special mess halls for Caucasian staff: a "staff mess," which was a room set inside the Blue Mess, and an "administrative mess" in the former press room on the roof of the racetrack grandstand. The administrative mess was restricted to administrative heads of departments and accommodated up to thirty persons per meal. An inspection by army officers found that while the food came from the government stock, the actual meals were different from the camp's centralized meal plan. The kitchen staff admitted that they did take into account the wishes of their client when preparing meals. Also, the administrative mess had four cooks and four waiters operating the mess, "a rather large force for such a small mess hall," as the inspectors noted. In fact, there was one cook for seven clients as opposed to one cook for 600 clients in the regular mess halls. [26] The WCCA first provided 30 Caucasian cooks, who were released as Japanese American cooks became available.

A report found that food was lost nearly every night from several mess halls as the internal police helped themselves to food during their night shifts. The army reminded the administration that Caucasian staff was to use Mess No. 1 exclusively and that they were to be charged for their meals. [27]

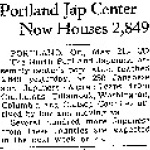

Camp Population

Santa Anita's inmates came mostly from Los Angeles County with smaller numbers from Santa Clara, San Diego, and San Francisco Counties. The first major group inducted were 587 Nikkei from the Los Angeles harbor area on April 3. [28] During the next two days another 1,910 arrived from the same area. On April 7, 637 Nikkei arrived from San Francisco, and the next day 1,131 from San Diego County. A total of 2,492 from southwestern Los Angeles arrived on April 13 and 14, bringing the population up to almost 7,000. On April 28 through May 1, 5,204 from areas just west of downtown Los Angeles—including the area Japanese Americans referred to as "Seinan"—arrived, bringing the number up to almost 12,000, 8,500 of whom were housed in the horse stables as barrack construction continued. May 6 to 9 saw another 4,000 inducted from Southeast Los Angeles and from the Los Angeles Chinatown area just north of Little Tokyo. The final large group arrived in the last week of May, 2,112 from Santa Clara and San Jose counties. By June 2, with a total of 18,527 detainees, Santa Anita was the 32nd most populous community in California. [29]

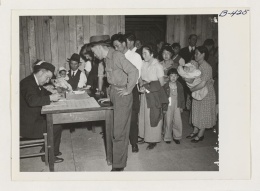

Japanese Americans arrived by bus, in private cars and by special electric trains. Bus arrivals were handled at the rate of 700 per hour. All luggage was checked before it was delivered to the barracks.

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 2 | April 5 | Los Angeles Harbor area and Long Beach | 2,497 |

| 4 | April 8 | Central San Diego County | 1,238 |

| 5 | April 7 | San Francisco | 629 |

| 6 | April 14 | Los Angeles (southeastern area) | 2,444 |

| 10 | April 29 | Los Angeles (west central) | 626 |

| 11 | April 29 | Los Angeles (west central) | 1,534 |

| 21 | May 1 | Los Angeles (west central) | 1,235 |

| 22 | May 1 | Los Angeles (south central) | 1,855 |

| 31 | May 7 | Los Angeles (east) | 2,112 |

| 33 | May 9 | Los Angeles (Chinatown and area north of Lil' Tokio) | 1,880 |

| 54 | May 14 | Los Angeles (Pasadena) | 297 |

| 96 | May 30 | Santa Clara County | 2,146 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than thirty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

| U.S. Citizens | |||

| Under 16 | Male | 2,232 | 12.32% |

| Female | 2,198 | 12.13% | |

| 16 to 40 | Male | 3,789 | 20.92% |

| Female | 3,639 | 20.15% | |

| Over 40 | Male | 135 | .75% |

| Female | 57 | .31% | |

| Total | 12,050 | 66.58% | |

| Aliens | |||

| Under 16 | Male | 5 | .03% |

| Female | 17 | .09% | |

| 15 to 40 | Male | 481 | 2.66& |

| Female | 466 | 2.57% | |

| Over 40 | Male | 3,047 | 16.82% |

| Female | 2,037 | 11.25% | |

| Total | 6,053 | 33.42% |

Sourse:Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

Among the inmates were the then-unknown actor George Takei and twenty-nine World War I veterans who had started an American Legion post.

There were 148 births and 31 deaths in Santa Anita. [30]

On August 26, the emptying of the Santa Anita detention facility began with 901 detainees (235 by bus, and 666 by train) being the first to be transferred for long-term confinement, leaving for the Colorado River (Poston) WRA camp. During the next two weeks, 4,500 detainees, formerly from Santa Clara and Los Angeles, left for the Heart Mountain incarceration camp in Wyoming. WRA camps receiving inmates from the Santa Anita Assembly Center were: Heart Mountain (4,708), Rohwer (4,419), Amache (3,062), Jerome (2,913), Poston (1,503), Gila River (1,271), Topaz (550), and Manzanar (65). [31]

| Departure Date | Camp | Number |

| August 26 | Poston | 870 |

| August 27 | Poston | 540 |

| August 30 | Heart Mountain | 608 |

| September 1 | Heart Mountain | 597 |

| September 3 | Heart Mountain | 595 |

| September 5 | Heart Mountain | 583 |

| September 7 | Heart Mountain | 586 |

| September 9 | Heart Mountain | 561 |

| September 11 | Heart Mountain | 541 |

| September 13 | Heart Mountain | 532 |

| September 17 | Amache | 495 |

| September 19 | Amache | 524 |

| September 20 | Rohwer | 503 |

| September 21 | Amache | 514 |

| September 22 | Rohwer | 522 |

| September 23 | Amache | 500 |

| September 24 | Rohwer | 496 |

| September 25 | Amache | 452 |

| September 26 | Rohwer | 494 |

| September 27 | Amache | 457 |

| September 28 | Rohwer | 492 |

| September 30 | Rohwer | 453 |

| October 2 | Rohwer | 480 |

| October 4 | Rohwer | 417 |

| October 6 | Rohwer | 389 |

| October 7 | Topaz | 550 |

| October8 | Jerome | 510 |

| October 10 | Jerome | 457 |

| October 12 | Jerome | 476 |

| October 14 | Jerome | 472 |

| October 16 | Jerome | 355 |

| October 17 | Gila River | 533 |

| October 18 | Gila River | 514 |

| October 19 | Jerome | 386 |

| October 26 | Gila River | 224 |

| October 26 | Poston | 93 |

| October 26 | Manzanar | 65 |

| October 27 | Heart Mountain | 105 |

| October 27 | Amache | 120 |

| October 27 | Jerome | 257 |

| October 27 | Rohwer | 173 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

Staffing

As was true at many of the temporary WCCA camps, a good portion of the staffing came from the ranks of the WPA, including Camp Director Russell Amory, Southern California Administrator of the WPA. On August 8, the Fourth Army headquarters ordered the "immediate" replacement of Amory as manager, made "mandatory" by "careful investigation of the facts." On August 13 Amory was replaced by assistant director Gene W. Wilbur. Amory had previously antagonized the army when he criticized the intrusive behavior of the internal police during the mess hall strikes (described below), so it seems likely that the army considered him to be too lax and overly compassionate to the inmates. [32]

Other key staff: [33]

Service director: Everett G. Chapman

Chief, recreation and education: Edward J. England

Works director: William A. Towle

Director of housing and feeding: G.B. Brewster

Chief, lodging section: Alan A. Alexander

Chief steward: Al Fields

Health section supervisor: Everett G. Chapmann

Supervisor of supplies: William H. Barber

Fire chief: Raymond P. Peterson

Police chief: Sherman F. Carter (released in May and replaced by F.H. Arrowood, who was succeeded by C.O. Dawson, who was succeeded by Roscoe Davis on August 12)

Public relations officer: Leslie W. Feader

Superintendent of camouflage net project: G. W. Fitzpatrick

Personnel relations officer: Guy E. Wilkinson

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

In most " assembly centers " the incarcerated elected a body of representatives to lend more leverage to their voices and to act as a liaison between them and their custodians. Santa Anita was no exception to this rule. Shortly after their arrival community leaders put forward their plans to the camp director and on April 30, Amory informed the WCCA that "self-government at the Center is being inaugurated and elections will be held shortly. It is the plan to set up a 'government house' where all matters pertaining to self-government will be centralized." [34]

An extra "constitutional edition" of the Pacemaker on June 2 printed the constitution and by-laws of the planned self-government assembly. All residents who were at least twenty-one years old were allowed to vote. Santa Anita was divided into seven districts, each with seven sections (essentially equivalent to blocks in other assembly centers), and each section was to elect one representative. The election took place on Friday, June 5. 10,356 eligible voters were registered and a total of 5,924 votes were cast. More Issei than Nisei voted, and more Issei candidates were elected. On June 10, the 49 sectional representatives met for the first time in the government house in the presence of the personnel relations officer to elect one representative for each of the seven districts. This seven-man council, consisting of four U.S. citizens and three aliens, was to be the main liaison between the inmates and their keepers. Regular meetings were scheduled for every Wednesday and a weekly report of the proceedings was to be sent to the camp director. [35]

However, once the district councilmen had been elected, Santa Anita's director refused to confirm them. This hesitation most likely went back to a WCCA letter from May 31 to all camp directors, in which the army expressed "grave concern" about self government. On June 22 the army provided updated rulings on community government. A major change was the exclusion of Issei from participating in any form of self-government. Camp Director Amory suggested to the WCCA that he appoint an advisory council that included aliens proportional to their population. He argued that the exclusion of Issei would "arouse the animosity of the alien Japanese" who would refuse to accept work orders and withhold their moral and material support for running the center. Amory stressed that the Issei had been very helpful so far, being steady and reliable in their performance of duties and respected in their community. [36]

Shortly after the June 22 announcement, another proclamation was issued through which the WCCA further regulated community government meetings in the temporary concentration camps. Administrative Notice No. 13, dated June 25, prohibited the discussion of international affairs, as well as national, state, county or city politics. Also, the use of the Japanese language was forbidden. Before each meeting an agenda had to be submitted to the public relations officer (essentially a censor) for approval. There had to be at least one American-born Nisei present "to act as an observer," and a complete stenographic transcription had to be submitted within 24 hours after the meeting. [37]

One week earlier, on June 18, there had been a meeting at the Santa Anita government house, held partially in Japanese, with no Caucasians present. During the meeting the councilmen discussed requesting a visit by the Spanish consul to investigate conditions at Santa Anita (which was vehemently opposed by at least one Issei), as well as a petition asking for a Japanese language section in the camp newspaper. A light scuffle broke out and was brought to an end when the internal police arrived and dissolved the meeting. The six Issei present were arrested, among them the chairman of the self-government council Tozaburo "Thomas" Sashihara. Shortly after, the five Nisei present were arrested as well. On June 21, FBI agents arrived at the camp and questioned the eleven suspects. The following day, the FBI arrested the six aliens and transferred them to internment camps. The five Nisei remained in the camp jail for violating the army's meeting rules. [38]

With this, the work of the representative body was halted and the topic of community government completely vanished from the pages of the Pacemaker . On July 4, each sectional representative was compelled to sign a resignation letter, effectively dissolving democratic community government at Santa Anita. The camp director apparently appointed a seven-man advisory council, but there is nothing known about its activities. [39]

Education

After the camp had been running for a month, Armory wrote to his WCCA superiors that he thought the California State Department of Education was developing a schooling program but that he had heard nothing from them so far. [40] As he soon learned, the WCCA had no plans for schools or other educational opportunities, and educational programs were left to the initiative of the Japanese Americans. At Santa Anita, educational activities were organized by the recreation department, unlike in other camps which had an independent education division.

The continuation of education for children, whose school terms had been interrupted by the exclusion, had top priority. By June 2, 130 teachers had been recruited from the population and 2,470 people had enrolled in educational programs. High school, middle school, and elementary school classes were taught in the lobbies of the grandstand where "teachers had to shout so much that they become hoarse." [41] Thanks to contributions from city and county schools, sufficient textbooks arrived for most grades. [42]

The Los Angeles school system arranged for a mass graduation on June 26 for their former junior high and high school students. Vierling Kersay, Los Angeles City Superintendent of Schools delivered the commencement address. Grammar and high school classes continued after graduation until they were disbanded late in August. [43]

Eventually educational opportunities were created for all ages. A nursery school for 200 children up to 5 years of age started by mid-May. Despite their treatment by the government, Americanization classes were quite popular with the Issei with five hundred enrolling in English classes and four hundred in "Democracy Training" (i.e. American history). Questionnaires were sent out by the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council to all high school graduates and college students who wished to continue their formal education. [44]

Medical Facilities

As in all WCCA camps, health care was marred by the lack of facilities and medical supplies. Fever and digestive problems were the most widespread medical conditions due to the unbalanced diet and the unfamiliar heat. Before the camp hospital was opened on April 28, patients were sent to the Los Angeles County Hospital. However, when there was an emergency, it often took several hours for an ambulance to arrive. [45] During April there were 174 home calls and 8 emergency ambulance calls. Twenty inmates were sent to the county hospital. The US Public Health Service and the L.A. County Health Department pledged their support, mainly doing inspections and service work. They provided one public health doctor, one sanitary inspector and two public health nurses. [46]

By June 2, 235 inmates were employed as medical staff, the number rising to 304 during August, including 8 physicians, 11 dentists, 29 nurses, 56 dieticians and aides, and 200 other employees. [47] There was one medical doctor for every 3,000 Japanese Americans. Dr. Norman Kobayashi was named physician in charge of the hospital. The hospital was equipped with 150 beds, but due to a shortage in linen only about a hundred were in service. In the course of the first weeks, each individual received inoculations against typhoid and small pox. Children from six months to ten years of age in addition were given diphtheria shots. [48] While there was no dental equipment as of May 20, by July 31, a dental clinic was handling some 300 persons a day. [49]

By June there were two ambulances stationed at the camp in order to react more promptly to emergency cases, and complaints regarding medical facilities somewhat decreased. By mid-September, 8,262 patients had received 25,245 treatments in the out-patient clinic. The dental clinic counted more than 3,000 patients with an average of five treatments each. [50] According to the army's Final Report there were 37 deaths and 194 births. [51]

Policing and Unrest

In June, the army ruled that a twice a day a head count was to be held, one at 6 a.m. and one at 9:30 p.m. (with lights out at 10 p.m.). The camp director wrote that with the cooperation of the self-government assembly, "residents have cooperated excellently." [52]

As at other WCCA camps, a municipal police officer was employed as "chief of interior security" by the army. In Santa Anita, Chief Sherman F. Carter supervised 19 police officers who inspected all incoming and outgoing parcels for contraband, supervised the visiting room, and patrolled the camp grounds. They were aided by 80 inmate "officers" who formed an "auxiliary police". [53]

The records of the internal police document police insulting inmates with impunity. The dismissal of internal Police Chief Carter and Captain Edwards by the chief of the WCCA Interior Security Branch indicate that the treatment of Japanese Americans must have been poor, even by army standards. In one example a husband was verbally abused for turning on the lights after 10 p.m. in order to care for his ailing wife. Unwilling to listen, the patrolman on duty and the first officer had nothing but insults as the inmate insisted on lodging a complaint. [54] All in all, Santa Anita had four police chiefs and thus the highest turnover rate in any of the WCCA camps.

Statistically, with 29.7 offenses per 1,000 persons per year the rate was above the "assembly center" average of 20.6. The FBI's crime report registered 226 offenses for Santa Anita. [55]

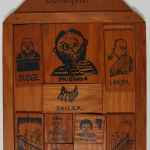

One of the concerns of the internal police at Santa Anita was organized gambling. During a gambling raid on May 24, 35 persons were arrested and more than $3,000 in cash seized. The raid was a joint operation of the local sheriff's office, the camp police, and army authorities, lead by Chief F. H. Arrowood of the internal police. It was precipitated by complaints by camp inmates who "were forced to support the gambling games by former henchmen of Hideichi Yamatoda, former gambling king in Little Tokyo," losing considerable sums of money in the process. While Santa Anita's public relations representative contested this version, it didn't offer an alternative explanation. Ten Japanese Americans were eventually brought before court and pleaded guilty at the Monrovia township court. Most were sentenced to a $100 fine or 50 days in jail. [56]

Santa Anita also saw several protests and strikes, most relating to working conditions. (See also Santa Anita Camouflage Net Project .). On June 23, for instance, two dishwashers were released from Mess Hall 4, the recently designated family mess, after disobeying a direct order from the Caucasian chief steward regarding the handling of the chinaware. In protest of the firings, all dishwashers went on strike. When the dishwashers still refused to work in the evening, the camp director was called to mediate. During a meeting the following morning, the dishwashers presented a long list of grievances: they requested an increase in personnel from 18 to 22 per wing; to be paid for an eight-hour-day instead of only for the time they worked (about seven hours); to be provided with more tubs, linens and towels; and more. They also complained about the chief steward because he presumably had refused to do the necessary requisitions, had allowed Caucasian staff to eat at the mess hall (sometimes leaving nothing to eat for the dishwashers), and was patronizing to the Japanese American workers. After listening to their grievances, the camp director promised to re-employ the two dishwashers after a period of time, while explaining the difficulty of recruiting new kitchen staff and warning that incidents like this would sway public opinion to put camps under military control, which nobody wanted. He also ruled that the chief steward was to remain, as he did his job well as far as Amory was concerned. [57]

According to the official army report, Santa Anita was the only WCCA camp in which a "disturbance of serious proportions occurred [...]." [58] The so-called Santa Anita Riot on August 4 originated in a routine search for contraband (including Japanese language books and phonograph records), and an unannounced confiscation of hot plates. Rumors of jewelry and cash being taken spread rapidly. Some people besieged administration offices to complain about police robbery and mistreatment. The recreation department sent their staff home to "protect their belongings" and crowds prevented the inspectors from entering some barracks. The internal police were harassed and one suspected informer of mixed Japanese and Korean ancestry was severely beaten. 200 military police were called in to silence about 2,000 protesters. Once the soldiers entered the camp the crowds dispersed quickly. Martial law was declared, and that night the residents were confined to their barracks with no meals served. Military police patrolled inside the center for three days, withdrawing from the camp on the evening of August 7. It was the only instance in which the army declared martial law in any of the WCCA camps, and it was concluded that the disturbance was spontaneous, a result of overzealous officers and poor liaison that prevented the chief of interior security from reacting in time. [59] However, there were also other complaints underlying the protests: a case of liquor smuggling uncovered involving Caucasian mess hall supervisors and cooks; evidence of homes being broken into by internal police without knowledge of the inhabitants; and a general distrust of internal security police, as well as dissatisfaction about food and "the deplorable" efforts to provide education for the children. It also seems that the military held the camp director at least partly responsible, as Amory was replaced on August 8.

Conflicts did not only occur between keepers and detainees, but also among the administrative staff. The most pervasive conflict was between the internal police and the camp management. A bone of contention was the right of the internal police to enter the mess halls. Technically the police had the right to investigate any problems, including in mess halls. On the other hand, the management had the responsibility for labor relations issues. This led to a major disagreement between Chief Dawson from the internal police on the one hand and Amory and Housing and Feeding Director G. B. Brewster of the camp management on the other. On July 27, dishwashers at Mess No. 6 stopped working in protest over the lack of towels that had been ordered weeks before but had not been delivered. Brewster's assistant was called in and, after a brief discussion, managed to get the dishwashers working again. However, there was another strike shortly after caused by an overzealous policemen who started a criminal investigation into the first work stoppage. The camp manager argued that officers should not enter the mess halls unless he or the mess hall superintendent asked for it, while the police insisted this was their responsibility to go to any place in case of trouble. The camp manager also contended that officers were "apt to aggravate the affair" and that "many officers were of such low mentality that they could not handle the cases." The police chief was apparently hurt, denying that officers incited trouble and argued that even though labor disputes were not his business, there was always the danger of "subversive activities." [60]

This argument was essentially a conflict of governing styles: the police was taking an authoritarian approach, treating Japanese Americans as prisoners whose protests were to be treated as criminal or subversive acts; the administration, by contrast, tended to consider the causes of discontent and tried to solve them without criminalizing the incarcerees. The police chief was obviously hurt and appealed to his WCCA superior, hoping the military would side with his aggressive policing style. And indeed, the Civil Affairs Division asked the WCCA chief to release Brewster. [61] However, the WCCA decided that since only two months of operation remained "it is not advisable to remove any of the center management staff at present". [62]

This was not the first time army officers had visited the camp to mediate between the internal police and administration officials. On June 15, representatives of the WCCA and the Fourth Army had visited the camp, investigating the lack of cooperation between interior police and center management. [63] In his report from August 21, Camp Manager Wilbur noted that a "close cooperation has developed," and that "[t]he atmosphere has completely changed," as problems were quickly addressed. [64]

Overall, however, relations within the administrative staff as well as inmate-keeper relations seemed to have been more tense in Santa Anita than in other WCCA camps. In addition to several incidents requiring the military's mediation, the official Red Cross report noted, that while "in most centers the evacuees spoke well of the management," in Santa Anita they observed "distrust and sullenness." [65]

Library

The library was a cubicle in the grandstand. It had several thousand books on its shelves—5,000 alone donated from the Los Angeles Public Library—and served 500 persons daily. It was open from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays, and Saturday mornings. [66] The ban on Japanese literature resulted in the removal of countless books. (Sacramento had the only "assembly center" library with a Japanese-language section. [67] ) Initially, only magazines were available to the public, but later people could check out four books per week. The head librarian was Anna Morikawa.

Newspaper

The camp's newspaper was the Santa Anita Pacemaker , published twice a week. The editor was Eddie Shimano , formerly an active member of the WPA Writers Project. The first issue appeared on April 18, with a circulation of 1,800, rising to 5,000 by June. Biweekly publication continued until October 7, 1942, making for a total of fifty issues, each four to six mimeographed pages, plus a final issue comprising 26 pages. It was the longest running of any of the purely "assembly center" papers. Explaining the name, Editor Shimano stated: "This newspaper is supposed to set the pace for the Japanese at the center [...]. A pacemaker in a horse race is the horse that leads the way for the others to a certain point, and that's what we are going to do." [68] The camp director repeatedly praised the paper, pointing towards its importance for morale building and the fact that it was "the only source supplying information on camp life and through which policy can be disseminated." [69] After Eddie Shimano left Santa Anita, Bob Hirano and Paul Yokota took over the editorship. The only females on the team were Tsuroko Katayama and Asami Kawachi. [70]

Religion

Religious freedom was guaranteed by the WCCA, though services in the Japanese language required the camp director's permission. By mid-April, five religious groups met for services and Sunday school in the recreation hall and the grandstand each weekend: Seventh Day Adventists, Catholics, two Protestant groups (Federated Protestants and the Holiness Association), and Buddhists. A month later, the number had risen to eleven. All denominations had their own Sunday school classes. A committee with Catholic, Buddhist and Protestant representatives suggested Caucasian preachers as guest speakers to be invited almost weekly, though the guests had to be cleared by the administration. The young people's Buddhist gatherings, for instance, were presided over by Reverend Latimer and Reverend Goldwater of Los Angeles who arrived on Sunday mornings to conduct services with Reverend Ishiura, a Nisei priest. The attendance of Buddhist services was relatively small—approximately five hundred—compared with several thousand in Protestant gatherings. Methodists had the largest following in Santa Anita. [71]

Before an official policy was formulated, an outside committee advised the camp management on religious policy and supplied religious leadership. Organized through the L.A. County Coordinator of Community and Church Life, the committee was composed of a Protestant, a Catholic and a Buddhist cleric. It also was subject to army regulations, that established that visiting ministers must be invited, that they do not enter the living quarters, that they do not take out notices or bulletins from the center, and that they leave the camp after the completion of the service. Also, they were not to be paid by other bodies for their service but according to the WCCA's pay scheme. One minister who took exception to this was Dr. Gordon Chapman [72] , whose visit on June 14 upset the camp management after he visited inmates in their living quarters, copied some camp bulletins and suggested that ordained ministers should receive some payment by outside church organizations. [73]

Recreation

Handicapped throughout by a lack of funds and equipment, recreational activities were nevertheless tremendous in scope. The diverse program ranged from marble contests, dances, and community sings to concerts, talent shows, model airplane contests, and more. Wrote one inmate: "Various recreational activities are constantly going on. Many softball and hardball leagues have been functioning; various clubs have been organized and entertainment of one sort or another is continually going on. The different departments [...] all have their private socials." [74]

Despite the summer heat, sports were very popular. Softball, hardball, basketball, badminton and sumō stimulated rivalry and competition and attracted hundreds of visitors to the Anita Chiquita field daily. More than seventy teams (including at least eight female teams) competed in five softball leagues drawing 2,000 to 3,000 spectators every night. Practically every night there were sumo contests drawing an estimated 2,500 viewers at the Anita Chiquita track. Weightlifting competitions were Sundays at 6 p.m. The camp even had a female judo team. By mid-August, a golf-driving range had been built.

By end of May, 440 Issei had signed up for English classes, 530 registered for swing dance, 150 for knitting and 100 for bridge. Shogi , go and hana games were most popular amongst older inmates, while the younger generation preferred poker or bridge.

The "Japanita Jive" was Santa Anita's first band and orchestra, from which the "Starlight Serenaders" developed, a 12-piece dance band that was coached by Larry Kurtz who was allowed in the camp for that purpose twice weekly. All but the pianists used their own instruments. Saturday night dances took place in front of the grandstand, attracting up to 1,000 people. Santa Anita had half a dozen Boy Scout troops and a PTA. Three Boy Scouts conducted daily flag-raising and lowering ceremonies atop the main entrance of the grandstand. [75]

Motion pictures were shown at the grandstand. On April 24, the Maryknoll Fathers presented The Gang's All Here with Frankie Darro. On the second movie night on May 29 Spring Parade was the feature film. The third night featured Champions , an early Charlie Chaplin film, and Deanna Durbin's Mad about Music (July 9 and 10). [76] Some 5,000 people attended the screenings, though some thought it wasn't worth the trouble, since one could hardly see the picture on the small screen from the grandstand, and the sound was poor as well. [77]

Friday nights were designated "Issei nights," featuring a program of Japanese dances and music presented in the recreation hall. In district VII, bon dance rehearsals had quite a following, until it was forbidden by the camp administration. The less visible haiku and tanka groups escaped a ban despite meeting frequently. [78] On June 29, an administrative notice informed the inmates "to deliver immediately to Room 055, underneath the grandstand [...], all phonograph records which are Japanese martial music, either vocal or instrumental, and all recorded speeches, plays, poems, stories, or other recordings in Japanese dialect." [79] A previous order had designated all Japanese literature, including English-Japanese dictionaries, except religious books, as contraband.

Store/Canteen

The first canteen opened April 21 and was operated by the army. It was open from 9:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. [80] By May 6, it was making $1,700 per day. [81] By May 25, three canteens were operated by the WCCA, which assumed control from the army. Coupon books were issued by the administration as the sole means of payment. Each canteen was run by a Caucasian supervisor and employed some twenty workers. In the first month only soft drinks and candy were sold as the administration waited for the army to approve a list that included laundry soap, cosmetics and toilet articles, as well as simple drugs. [82]

Visitors

Visitors could be received at the Baldwin Avenue gate. Due to the great number of visitors, visiting was severely restricted: only direct relatives and business representatives were allowed to apply for a visitor's pass (at least five days in advance), and visiting hours were only 2 to 4 p.m. In order to meet the demand for space, a "visitors house" was opened on June 24, with a capacity of 150 persons. One week a day was reserved for each of the seven districts, so one could see outside friends no more than once a week. Visiting hours were extended to 1 to 4 p.m. and visiting time restricted to one-half hour. With the visitors house operating, there were an average of 100 visitors weekdays and 150 on weekends. [83] Still, the American Red Cross, having visited Santa Anita on July 20 and July 31, criticized the Santa Anita detention center, along with Puyallup, for not providing sufficient visiting opportunities. [84] Likewise, ministers and other civilians who visited several "assembly centers" for humanitarian purposes claimed that Santa Anita was the "most inhospitable to Caucasian visitors." [85]

Other

Santa Anita was the only "assembly center" to have a camouflage net factory, a war industry enterprise that gave Nisei the opportunity to contribute to the war effort. See the separate article on the factory.

There was one main post office and branches in all seven districts of Santa Anita. The main office, headed by Leo Mauch, received at its peak 397 money orders daily, as well as 612 COD, 800 parcel post articles, plus 3,500 to 4,000 letters. All packages were inspected before delivery. The number of outgoing letters was approximately 5,500 daily. Also, by June 12, the post office had sold approximately $5,000 worth of war bonds, despite the inmates' lack of income. [86]

The army was concerned that WCCA-issued bulletins were going out with letters. During the first weeks in the still small post office, Caucasian staff would sift through the letters and "extract letters addressed to known newspapers." This gave them a "means of control," as Public Relations Officer Leslie Feader put it. With the post office run largely by inmates and outgoing mail running in the thousands, Feader admitted that there was no way to control what left the camp. He recommended sending out the Santa Anita Pacemaker and convinced its editor to send no information to outside newspapers. Those releases Eddie Shimano faithfully handed over to Feader to be released were all held back by Feader, who urged the army to prepare their own stories about the camp "to guide public opinion." [87]

On August 10, ACLU member Kyoshi Okamoto submitted a letter to the administration, informing Nisei residents of the Wakayama case , in which Santa Anita inmate and World War I veteran Ernest Wakayama challenged the constitutionality of the evacuation orders and Public Law 503 , and asking for their support. The administration refused to publish the letter in the camp newspaper. [88]

Among the inmates was Tamie Tsuchiyama , a trained anthropologist from the University of California. Tsuchiyama worked as participant observer for Dr. Dorothy Thomas and her Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS). As a part-time employee she received $ 62.50 a month for her writings on Santa Anita. She also worked as supervisor for women camouflage workers and left the camp on August 10, heading for Poston. [89]

Around 200 Japanese Americans volunteered for farm work and left the camp for Idaho starting in June. [90]

Chronology

April 3

The first group of Japanese Americans are inducted. Blue Mess Hall in the stable area opens.

April 5

Milton Silverman from the

San Francisco Chronicle

arrives to write a feature on Santa Anita.

On April 7

637 Nikkei arrive from San Francisco.

April 8

1,131 Nikkei arrive from San Diego.

April 24

First movie shown.

April 28

Hospital with 160 bed capacity opens.

April 29

The first baby born in Santa Anita is Franklin Koji Yoshida. He is the third child of the Nisei parents from Gardena.

May 2

The second baby is born in Santa Anita, named Edward Kenichi Fujimoto. He is the first child of the Nisei parents from Orange County.

May 8

The first baby girl is born on Mother's Day to Yutake Inouye.

May 11

The price of Coca Cola in the canteen is raised from 5 cents to 7 cents due to a bottle shortage. It goes back to 5 cents shortly after empty bottles are returned.

May 13

First informal meeting of voluntary sectional representatives held in the newly constructed Government house to formulate plans for a community government in Santa Anita.

May 17

Itsusuke Zaima, pioneer flower grower of Montebello, dies at the Los Angeles County hospital.

May 20

Partitioning of the barracks is finished.

May 24

35 inmates are arrested in a gambling raid.

May 27

Experiment in family style feeding starts in Mess Hall 4 after it has been completely equipped with silverware.

May 29

A Signal Corps motion picture unit of fifteen men start filming a government documentary film of the operation of the camp.

June 1

First wedding at Santa Anita.

June 10

The forty-nine sectional representatives meet for the first time. They elect one representative for each of the seven districts. The council is sworn in by Personnel Relations Officer Guy E. Wilkinson but never confirmed by the camp director.

June 15

Carey McWilliams

, California Commissioner of Immigration and Housing, visits Santa Anita. By that time he had become highly critical of the forced expulsion of the Japanese Americans.

June 16

Approximately 1,200 workers of the camouflage net factory stage a strike, demanding higher pay.

June 23

Dishwasher strike at Mess Hall 4.

June 25

Administrative Notice No. 13, dated June 25 is posted, severely restricting freedom of assembly and freedom of speech.

June 26

First graduation ceremony for over 250 pupils graduates from Los Angeles city and county schools.

June 27

Diphtheria inoculations for children start at the camp hospital.

July 4

The forty-nine elected sectional representatives are compelled to sign resignation letters, effectively dissolving democratic self-government at Santa Anita.

July 8

Ban of Japanese literature announced.

July 15

Distribution of second pay check for the period between April 15 and May 15 to 3,964 inmates, amounting to a total of $22,117.89.

July 24

Yamato Ichihashi

and his wife Kei leave Santa Anita for

Tule Lake

to join their son Woodrow.

July 25

Distribution of third pay check for the period May 16 to June 15, a total of 6,430 being distributed.

August 4

A routine search for contraband and an unannounced confiscation of hot plates turns into the so-called Santa Anita riot. An inmate of Japanese-Korean ancestry and suspected informer is beaten. About 200 military policemen enter the camp and take over control.

August 7

Military police are withdrawn after the so-called Santa Anita riot.

August 9

First kite contest by the Cub Scouts conducted at Anita Chiquita field.

August 12

Roscoe D. Davis is named new chief of internal police. He is the Santa Anita's fourth police chief, after Carter, Arrowood, and Dawson. Also, former assistant director Gene Wilbur is confirmed as new camp director.

August 18

A 20-chair barber shop, staffed by seven women and sixteen men, opens at 21 Gillie Avenue.

August 21

National Japanese American Student Relocation Council

visits Santa Anita interviewing 46 students; the interviews continue for a week.

August 23

Population peaks at 18,719.

August 24

A fire breaks out in the Jockey Grandstand caused by butane gas leaking from an outlet.

August 26

The first contingent leaves Santa Anita: 870 persons leave for the Colorado River WRA camp.

August 30

The first group of 608 leaves for the Heart Mountain WRA camp.

September 6

In the morning a fire breaks out in Canteen No. 2, probably due to faulty wiring in the ice cream refrigerator. The barrack is destroyed and two adjacent barracks scorched.

September 10

Last talent show held is attended by 7,000.

September 14

All books are to be returned to the library in preparation for the move to the WRA camps.

September 17

The first group of 495 leaves for the Amache WRA camp.

September 22

First group of thirty-four leaves to help in the beet harvest in Montana.

September 26

Last community dance is held in front of the grandstand. Center hospital closes.

September 30

Population drops to 6,700, most of whom are deported to Jerome and Gila River over the final days.

October 6

The last 389 of over 4,200 persons deported the Rohwer WRA camp leave Santa Anita. Approximately 5,000 remain in camp at this point.

October 7

Final issue (no. 30) of the

Santa Anita Pacemaker

published.

October 27

The last contingent of 173 leaves for the Rohwer WRA camp.

Quotes

On the mess hall and sanitary situation:

"Shortly after arrival one had to stand from forty-five to seventy-five minutes for a meal [...]. Then we had to get in line for showers and washing. And what facilities! Not only [was] the number very limited but a great change in privacy, cleanliness, aesthetics and convenience from our homes [...]. Early every morning one can hear [...] the rumble of wagon wheels about 5:30 a.m. What is it? It is the sound of women going to wash. Why so early? Because if they don't go at that early hour, they have to wait in line."

Ikuko Kuratomi, 1942

[91]

On the administration at Santa Anita:

“I did not like the WCCA administration in Santa Anita because they were too wishy-washy in policies. A few of the personnel in the administration were sympathetic. Most of the nisei thought of the WCCA as being glorified WPA workers. I did not have very many contacts with the administration so that I did not have too bad an opinion of them. However, I think that if they would have been more consistent in their policy, the people would have had more respect for the personnel. We could not trust them at all because they were always changing their minds about policy and they would think of new things out of the clear sky without preparing the people first. We just couldn't get any confidence in them when they did things like that.”

Chidori Ogawa, 1943

[92]

On the visitor's area:

“I still managed to keep up my contacts with the outside. I could not get over the feeling that I was in a jail. We had a special visitor's house for our friends to come to. There was a long table running down the center and we had to stay on the other side of the table, five feet across from our friends. We couldn't even reach over to shake hands or pass anything across. There were guards there to enforce the rules. Then another thing, we could only visit with our friends for a half hour even if they had come from a long distance. I resented this more than anything in Santa Anita as I felt that it was an insult. I just did not feel like having any visitor at all to let them go through this awful experience. After the riot, things were even more stricter and it became more and more like a jail.”

Chidori Ogawa, 1943

[93]

“The thing which irritated me the most was the stupid visiting regulations. It was a source of discomfort to me because the internal security would even listen in to our conversation. They didn't allow any of our friends to pass over presents to us since they had to be opened and examined at the gate. My guardians would bring me huge cakes and baskets of fruit but the inspectors would dump out and poke through everything in order to see that no dangerous weapons were smuggled in.”

Shizu Watanabe, 1943

[94]

On the food:

“The food at Santa Anita was terrible. Sometimes I would go into the mess hall real hungry and find some cheap smelly sausage and carrots for our bill of fare. I would nibble at it and then walk over to the canteen in order to fill up on something else. I don't think we ever had enough food there or if it were in large quantity it was no good. The food at Heart Mountain was better though and much more healthful. It seems that most of the trouble in camp was over the food situation.”

Robert Kinoshita, 1943

[95]

On the stables:

"From the outside, Santa Anita looked wonderful and impressive, but I did not like it when I was put in a horse stable right away. It was dirty and it smelled like horse urine. I could not understand why we were put it (sic) a place where animals had lived. It was not even sanitary. We were not used to living that way so that we made an application to go to one of the barracks near the hospital so that I could get to see the doctor easier. But we had to spend a week in that dirty stinking stable before we got to move. I felt sorry for some of those people who had to live in the stables for four and five months. That first week made my spirits go down low."

Chutaro Shimamoto, 1943

[96]

On social life:

"I was enjoying my life at Santa Anita because there were so many activities going on, and it was the first time that I had a chance to meet so many Nisei boys. We were all on an equal basis so that I didn't see things any differently than they did after a while. I thought it was better to have fun than sit around and brood about the matter because that would not have gotten us any place. The novelty of all this camp life and the activity was very exciting even though I had my stray moments of uneasiness."

Katsuko Yamamoto, 1944

[97]

Aftermath

After the closing of the "assembly center" the site became "Camp Santa Anita," a training facility for 20,000 army ordnance troops. It was the largest army ordnance training center on the West Coast and more than 100,000 soldiers were trained here until November 1944. Later, it served as a POW camp holding captured German soldiers.

Santa Anita Park reopened in 1945 and continues to be one of the world's premier thoroughbred racecourses. The 1960s brought about a major renovation of Santa Anita Park, including a much-expanded grandstand as well as major seating additions. The Santa Anita Racetrack was determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006, but continues to be threatened by developer's plans.

The Santa Anita Racetrack has been designated as a California Historic Landmark (No. 934, one for both the Santa Anita and the Pomona WCCA camp). However, there is no plaque specifically for the "assembly center" but a plaque remembering "Santa Anita during World War II," erected in 2001. [98] In 2000, Santa Anita was included on the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Most Endangered Sites list because of historically unsympathetic renovations being undertaken by the private owners. Although further study of the historic integrity of buildings related to the Santa Anita Assembly Center is needed, Santa Anita does appear to be the most intact of the surviving WCCA camps. The massive grandstand and other racetrack buildings present in the 1940s remain, as do the horse stalls of districts 1 and 2. The stables, of wood, are the same as in aerial and historical photographs. Japanese Americans occasionally return to see their former homes. [99]

In November 2009, the Arcadia Historical Museum featured the camp in the exhibition, "Only What We Could Carry: The Santa Anita Assembly Center" (November 10, 2009 to January 16, 2010). [100]

Notable Alumni

Ruth Asawa, artist

Dr. Yamato Ichihashi, and his wife Kei, formerly Professor at Stanford University

Chizu Iiyama, activist, social worker, educator

Chris Ishii, artist

Hikaru Iwasaki, photographer

Harry Kitano, sociologist

Yuri Kochiyama, activist

Norman Mineta, politician

Mary Oyama Mittwer, writer

Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi, race relations scholar

Eddie Shimano, journalist

For More Information

Print Sources

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Santa Anita section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16k.htm .

Chang, Gordon ed. Morning Glory, Evening Shadow: Yamato Ichihashi and His Internment Writings . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo. Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camp . Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1999.

Lehman, Anthony L. Birthright of Barbed Wire . Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1970.

U.S. Army. Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Gov't Printing Office 1943.

Sources Online

Bell, Alison. " Santa Anita racetrack played a role in WWII internment ." Los Angeles Times , Nov. 8, 2009.

The California State Military Museum. " Camp Santa Anita ."

Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives (JARDA) https://calisphere.org/exhibitions/t11/jarda/

Oyama, Mary. " This Isn't Japan ." Common Ground , Sept. 1942, 32–34. [Contemporaneous account of life at Santa Anita by an inmate.]

Santa Anita during World War II". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database." http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=52752 .

Santa Anita Park website: http://www.santaanita.com/ .

The camp newspaper, the Santa Anita Pacemaker , has been digitized and made available at the Densho Digital Repository, http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-146/ .

Footnotes

- ↑ Jeffery F. Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 158–59.

- ↑ Burton et al. Confinement and Ethnicity , Chapter 16. According to the Housing Section data published in the Santa Anita Pacemaker (Final Issue, p. 8), the numbers were 7,182 in stables and 11,411 in barracks.

- ↑ Letter, Ikuko Kuratomi to International House (Berkeley), July 26, 1942, National Archives II RG 499, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 3.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Russell Amory to Rex Nicholson, May 11 & May 20, 1942, Headquarters Hotel Whitcomb, Assembly Center Correspondence, Santa Anita Assembly Center, Microfilm Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; Santa Anita Pacemaker , May 15, 1942. Many other documents cited in this article come from the same section of the same reel and will subsequently be cited as "Reel ACB7, NARA, San Bruno."

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, May 6, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; Tamie Tsuchiyama, A Preliminary Report on Japanese Evacuees at Santa Anita Assembly Center , July 31, 1942, 1-3, 17, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, Call Number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.05, accessed on Oct. 20, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b022b08_0005.pdf .

- ↑ See Fact Sheets of the Assembly Centers in National Archives II, RG 499, WDC, Unclassified Correspondence, Boxes 56-59; Santa Anita Pacemaker , July 1, 1942.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 6-7.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 6.

- ↑ Letter, Kujo Saki to "Nadine", April 15, 1942; Letter, Rex Nicholson to Col. Evans April 25, 1942, both on Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Memorandum, Emil Sandquist to Lt. Col. K., July 23, 1942., NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Gene Wilbur to Emil Sandquist, August 21 & August 28, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Eventually 11,000 meals were served daily. Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 12, 1942, 3.

- ↑ Memorandum, H.A.R. Carleton to Rex Nicholson, June 13, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, April 30, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker, July 1 & July 18, 1942; Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report, 9.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report .

- ↑ Letter, Kuratomi to International House, July 26, 1942.

- ↑ National Archives II, RG 499, Box 47, Final Report, Assembly Center Branch.

- ↑ Memorandum, G.B. Brewster to Russell Amory, May 26, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, May 20 & May 26, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno. See also NA II, RG 499, Box 63 Folder 330.14, Criticism of Mess Halls.

- ↑ Letter, Edward Paulsen & Russell Amory to Rex Nicholson, June 18, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 10-11.

- ↑ As a result, the civilian WCCA Chief Rex Nicholson resigned, feeling unjustly accused by his superior of not taking sufficient care of the food supplies. See the exchange between Bendetsen and Nicholson in National Archives II, RG 499, WDC, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 63 (Folder "Criticism of Mess Halls").

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 8-9.

- ↑ Memorandum, Lt. Col. Frank Meek (F.A.) to Lt. Col. Claude Washburne (WCCA), July 29, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Memorandum, H.A.R. Carleton to Rex Nicholson, June 13, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Final Issue, 14.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 2, 1942.

- ↑ NA II, RG 499, Box 47, Vital Statistics. The army's Final Report (p. 202) lists 37 deaths and 194 births. See also Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 36-37.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Final Issue, 14-15; DeWitt, Final Report , 283-84.

- ↑ Letter, A.H. Moffitt (F.A.) to Emil Sandquist (WCCA), August 8, 1942; letter, Emil Sandquist to WCCA Operations Section Staff, August 14, 1942, both Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; Santa Anita Pacemaker , Aug. 12, 1942.

- ↑ For a list with Caucasian staff employed in Santa Anita, see Santa Anita Pacemaker , Final Issue, 6-7. See also folder "Santa Anita General, June, July," Community Analysis Reports and Community Analysis Trend Reports of the War Relocation Authority , 1942-1946.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, April 30 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , April 18, June 2, June 3, June 6, and June 12, 1942.

- ↑ Memorandum, Russell Amory to Rex Nicholson, July 6, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Administrative Notice No. 13, June 25, 1942.

- ↑ Exhibit B, Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 23, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans during World War II (Toronto: Macmillan, 1969), 182-83; Tamie Tsuchiyama, Attitudes , Oct. 3, 1942, pp. 25–27, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, Call Number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.05, accessed on Oct. 20, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b022b08_0005.pdf .

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Attitudes , 25.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, April 30, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Kuratomi to International House, July 26, 1942; Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 26-27.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 23, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 27, 1942, 1.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 27.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 37-38.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, Apr. 30, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ The camp director compiled a list with physicians, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, dieticians and optometrists for the WCCA, see letter, Russell Amory to Lester S. Diehl (Director Finance and Records at the WCCA HQ), May 20, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 37-39.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Sandquist, July 31, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Final Issue, 16.

- ↑ DeWitt, Final Report , 201-02; Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 2, 1942.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.; WCCA Information Bulletin No. 5, June 13, 1942, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) Collection, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, Reel 14, Slide 194; WCCA Information Bulletin No. 7, June 15, 1942, JERS Collection, Reel 14, Slide 177; Santa Anita Pacemaker June 2, 1942.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Apr. 24, 1942, 3.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, May 20, 1942; Statement by Joe Ishii, May 22, 1942. For another example of aggressive policing see letter, Jim Wiggs to Russell Amory, July 31, 1942, all on Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ DeWitt, Final Report , 219-21.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , May 29, 1942; Letter, Leslie Feader to Russell Amory, May 27, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno; L.A. Examiner , May 25 & May 27, 1942.

- ↑ A report of this incident was sent to the army. The responsible officer was satisfied with the camp director's response and estimated that only five per cent of the incarcerated were potentially causing trouble, "the boys from 17 to 21 years old who think they are tough customers." Letter, Edward M. Paulsen to H.A.R. Carleton, June 24, 1942; Meeting minutes, Russell Amory, June 24, 1942, both on ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ DeWitt, Final Report , 218.

- ↑ Anthony L. Lehman, Birthright of Barbed Wire (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1970), 62–63; DeWitt, Final Report , 218-19; Santa Anita Pacemaker , Aug. 8, 1942.

- ↑ Report to Major Ashworth, July 28, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ According to the Civil Affairs Division, "much friction that has existed [at Santa Anita] in the past has been directly attributed to M. Brewster's activities." Letter, W.F. Durbin to Emil Sandquist, Aug. 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Report, Sgt. J.C. McGowan to C.O. Dawson, July 27, 1942; Conference on disagreement between Interior Police and Management, C.O. Dawson, Gene Wilbur, C.B. Brewster, Russell Amory, July 28, 1942; Chronology on labor dispute in mess hall 6, C.B. Brewster to Gene Wilbur, July 28, 1942; Teletype, Russell Amory to Emil Sandquist, July 31, 1942; Letter, Norman Beasley, Emil Sandquist, Ray Ashworth to Karl Bendetsen, July 31, 1942; Letter, Major W.F. Durbin (CAD) to Emil Sandquist, August 2, 1942; Letter, Emil Sandquist to Major W.F. Durbin, August 5, 1942, all on Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Lt. Col. William Boekel to Col. Karl Bendetsen and Col. Ira Evans, June 17, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Wilbur to Sandquist, August 21, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Report of the American Red Cross, Survey of Assembly Centers in California, Oregon, and Washington, August 1942 (WDC and Fourth Army: Bound Volumes Concerning the Internment of Japanese-Americans 1942-1945, Vol. 22), 30.

- ↑ Andrew B. Wertheimer, "Japanese American Community Libraries in America's Concentration Camps, 1942-1946" (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2004), 76-77; Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 28-29.

- ↑ Wertheimer, "Japanese American Community Libraries," 68-69, 74.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Apr. 21, 1942.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, April 30, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ For vignettes on staff members, see Santa Anita Pacemaker , Oct. 7, 1942.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , July 31, 1942, 39-40.

- ↑ Gordon K. Chapman was executive secretary of the Protestant Church Commission for Japanese Service, an outspoken advocate for the Japanese Americans, and the official mediator between incarcerated Japanese American Protestants, the federal government, and churches.

- ↑ Letter, Everett Chapman (Service Division) to Gene Wilbur (Asst. Manager), June 15, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Kuratomi to International House, July 26, 1942.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 28; Santa Anita Pacemaker , May 5, 1942.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , July 11, 1942.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , May 29, 1942; Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report, 29; Letter, Chiyoko Nishimura to International House (Berkeley), July 26, 1942, National Archives II RG 499, Unclassified Correspondence, Box 3.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , 29-30.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Preliminary Report , July 31, 1942, 30.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , April 24, 1942.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, May 6, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Oct. 7, 1942.

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 1 and July 22, 1942.

- ↑ Report of the American Red Cross , 5, 29.

- ↑ Tsuchiyama, Attitudes , 22-23.

- ↑ Lehman, Birthright of Barbed Wire , 30; Santa Anita Pacemaker , June 12 & Oct. 7, 1942.

- ↑ Letter, Leslie Feader to Rex Nicholson, May 6, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Kyoshi Okamoto to all Nisei residents, August 10, 1942; "Wakayama Case to be argued in Federal Court" in Open Forum , August 8, 1942. When the Wakayamas were transferred to a WRA camp, they requested that the lawsuit be dismissed. See Oral History Interview with Fred Okrand, p. 119, online at http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/ .

- ↑ Santa Anita Pacemaker , Aug. 15, 1942; Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, The Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camp (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999), 29, 44-45. Tsuchiyama wrote three voluminous letters to Robert Lowie about her observations in Santa Anita.

- ↑ Narrative Report, Amory to Nicholson, June 2, 1942, Reel ACB7, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Kuratomi to International House.

- ↑ Chidori Ogawa, interview by Charles Kikuchi, Sept. 1943, p. 48, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, Call Number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.941, accessed on Oct. 24, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_box279t01_0941.pdf . This collection will be referred to subsequently at "JAERDA."

- ↑ Chidori Ogawa, interview, 48.

- ↑ Shizu Watanabe, interview by Charles Kikuchi, Oct. 1943, p. 56, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.984, accessed on Oct. 24, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b283t01_0984.pdf .

- ↑ Robert Tatsuya Kinoshita, interview by Charles Kikuchi, Oct. 1943, pp. 75–76, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.942, accessed on Oct. 24, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b283t01_0942.pdf .

- ↑ Chutaro Shimamoto, interview by Charles Kikuchi, Sept. 1943, p. 39, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.939, accessed on Oct. 24, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b283t01_0939.pdf .

- ↑ Katsuko Yamamoto, interview by Charles Kikuchi, Sept. 1944, p. 45, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.98, accessed on Oct. 24, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b283t01_0098.pdf .

- ↑ HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database, accessed on July 25, 2019 at http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=52752 .

- ↑ Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity , 369–72.