Tule Lake

| US Gov Name | Tule Lake Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Newell, California (41.8833 lat, -121.3667 lng) |

| Date Opened | May 27, 1942 |

| Date Closed | March 20, 1946 |

| Population Description | First to arrive were 500 volunteer residents from the Portland and Puyallup Assembly Centers. Others arrived from the Marysville, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, and Salinas Assembly Centers in California. Some were sent directly from the southern San Joaquin Valley. After it became a segregation center, the camp held people from California, Hawaii, Washington, and Oregon. |

| General Description | Located at an elevation of 4,000 feet on a flat treeless area in Modoc County, 35 miles southeast of Klamath Falls, Oregon, and 10 miles from the town of Tulelake. (The town is spelled as one word and the concentration camp as two.) Mt. Shasta is 50 miles away and visible on a clear day. The soil is sandy loam; vegetation is sparse grass and sagebrush. Winters are long and cold; summers are hot and dry. |

| Peak Population | 18,789 (1944-12-25) |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

Tule Lake was one of the ten concentration camps built to imprison Japanese Americans forcibly removed from the West Coast states during World War II. Following the ill-conceived loyalty questionnaire that was administered in early 1943 to the imprisoned population, inmates who refused to give unqualified "yes" responses were segregated to Tule Lake and unjustly labeled as "disloyal."

Site History and Features

The Tule Lake site is located in Modoc County, California, near the California-Oregon border, about forty miles southeast of Klamath Falls, Oregon and 10 miles south of the town of Tulelake. The area has an elevation of 4,000 feet above sea level, with flat and treeless terrain and sparse vegetation—mostly grass, tules, and sagebrush—growing in sandy, loamy soil scattered with tiny white shells from freshwater mollusks that once thrived in the shallow lake waters. Winters are long and cold and summers hot and dry, although the climate is considered relatively mild for a War Relocation Authority (WRA) site.

The concentration camp site was 1,110 acres; including the farmed areas, Tule Lake was 4,685 acres. It was situated on a dry lake bed created by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which drained the lake in 1920 to create farming homesteads that were allocated by lottery. Today, the former camp site is under federal and private ownership.

The Tule Lake site lies within a volcanic corridor in the Cascade range; to the south of Tule Lake are the lava beds that flowed from Medicine Lake Highlands. From State Highway 139, looking west, the most prominent geologic feature on the horizon is an 800-foot bluff composed primarily of basalt. Japanese American inmates named the bluff Castle Rock; local farmers and ranchers call it the Peninsula. To the east is a dome-like hill known to the inmates as Abalone Mountain, and to the locals as Horse Collar Mountain.

The area was the ancestral home of the Modoc tribe; however, a treaty with the U.S. in 1864 led to a decade of Modoc resistance against removal from their homeland. The legendary battle of Lost River took place at the geological and historic landmark, Capt. Jack's Stronghold in Lava Beds National Monument, where a band of fifty to seventy Modoc fighters held off an army battalion whose numbers rose to nearly 1,000. After five months of resistance against army efforts to roust them from the Stronghold, the Modoc were eventually overwhelmed by army reinforcements. On October 3, 1873, the leader of the Modoc, Kintpuash, known as Captain Jack, was hanged. Surviving tribal members were exiled to Oklahoma.

As WRA Camp

Construction on the Tule Lake concentration camp began April 15, 1942. By May 25, 1942, approximately 500 Nikkei volunteers had arrived to help set the camp up for inmates from the Sacramento , Pinedale , Marysville , Pomona and Salinas WCCA centers. Another 3,166 came directly to Tule Lake, which officially opened on May 27, 1942. The camp population originated primarily from the following counties: Sacramento, California (4,984), King, Washington (2,703), and Hood River, Oregon (425). The response of region's chambers of commerce was not welcoming, indicating, "they preferred to maintain the present character of the population [with] no orientals or negroes among its residents." [1]

Early public relations efforts by the WRA to dispel hostility toward the "Jap" camp had the opposite effect, creating distorted news reports and a persistent belief inmates were being coddled, enjoying a leisurely life eating steaks, ham and roasts while the local town folk suffered wartime shortages and rationing. When conflicts at Tule Lake flared up, sensationalized articles amplified local fears of dangerous Japanese POWs in their midst. The multiple instances of labor unrest at Tule Lake—including strikes over the lack of promised goods and salaries as early as August 15, 1942, a strike by packing shed workers the next month, and a mess hall workers protest in October 1942—were viewed by locals, not as an assertion of human dignity and civil rights, but as threatening acts of disloyalty.

The infamous loyalty questionnaire was mishandled at Tule Lake, causing widespread dissent. Pressure to answer ambiguous questions within a fixed deadline without adequate opportunity to discuss and evaluate them led to anger and civil disobedience. Several dozen young men in Block 42 refused to answer the questionnaire despite threats of $10,000 fines or twenty years in prison or both. For refusing to cooperate they were imprisoned in Alturas and Klamath Falls County jails, but since there were no criminal charges, the protesters were removed to Tule Lake isolation center where the Constitution did not apply. There, the army imprisoned several hundred of Tule Lake's protesters for nearly two months.

Mismanagement of this life-defining questionnaire contributed to Tule Lake having the largest number of Nikkei defined as "disloyal." (Those who refused to answer the questions or gave outright "no" responses were labeled "disloyal.") Answering "yes" but adding qualifying comments such as "when my rights are restored" or "when my family is released" also was defined as "disloyal." Of the 10,843 responses to the question 27 concerning military service, 3,218 or 30% refused to give unqualified "yes" responses. In their responses to question 28 of the loyalty questionnaire, disavowing loyalty to Japan, 15.6% were defined as disloyal because they refused to give unqualified "yes" responses.

The project director during the loyalty questionnaire fiasco was Harvey Coverley, who was replaced by Raymond Best, project director of the maximum-security segregation center. Prior to Tule Lake, Best had served as director of the WRA's jails, referred to as "Citizen Isolation Centers," at Moab , Utah and Leupp , Arizona. Tule Lake's first project director was Elmer L. Shirrell .

Under Best's tenure as director of the segregation center, Tule Lake became the largest WRA concentration camp, with a peak population of 18,789 inmates. By 1945, Tule Lake included a furniture factory, a bakery that produced goods for internal consumption, a shoe repair shop, a hog farm and slaughterhouse, a beauty shop, fish store, funeral parlor, several coop stores, and a tofu factory. Additionally, the farming areas grew enough to supply Tule Lake and other camps. Tule Lake had eight Buddhist churches and three Christian churches and four judo halls.

As "Segregation Center"

The Segregation Center was created on July 15, 1943, following pressure from Congress, the army and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). Tule Lake was designated as the segregation center, selected because of its capacity and the large number of persons who gave "incorrect" responses to the loyalty questions. Security at the Tule Lake site was increased when it became a segregation center. More barbed wire was added and an eight-foot high double "man-proof" fence was constructed to secure the maximum-security segregation center. The six guard towers surrounding the site were increased to twenty-eight, and a battalion of 1,000 military police with armored cars and tanks were brought in to maintain security.

Segregation was another forced removal for over 12,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent who were defined as "disloyals" and imprisoned at Tule Lake. Approximately 6,500 "loyal" persons from Tule Lake were sent to six of the other WRA concentration camps, excluding Manzanar , Poston , and Gila River . Segregation brought Tule Lake to the limit of its housing capacity; additional barracks were constructed for 1,800 Manzanar inmates who were not segregated until early spring 1944. In late spring, contingents from Colorado River, Rohwer , and Jerome arrived and were assigned to vacated barracks.

Under segregation Tule Lake became a very complicated prison camp, bringing together the leaders, organizers and the disaffected from the other nine camps, making up two-thirds of the segregation center's population. The remaining one-third of the population were the so-called "loyals" who did not want to leave Tule Lake for removal to another WRA camp, a decision that contributed to much turmoil at the segregation center. Almost immediately upon arrival, segregees organized to address unsatisfactory living and working conditions. However, Project Director Best was not inclined to negotiate with his prisoners or allow the self-government that was permitted at other WRA camps.

In the aftermath of a farm truck accident that resulted in five injured and the death of one inmate in October 1943, a work stoppage that began after the accident developed into a strike. Inmates demanded improved safety and working conditions and compensation for anyone injured while working. Best responded by firing the workers and bringing in strikebreakers—"loyal" inmates from the Poston and Topaz concentration camps—willing to pick the crops ready for harvest. The strikebreakers' pay was $1 an hour, enabling them to earn in two days what a Tule Lake inmate earned in a month.

In the midst of growing tension, on November 1, 1943, WRA National Director Dillon S. Myer visited Tule Lake. A negotiating committee of the Daihyo Sha Kai ("representative body") an organization of democratically elected leaders, met with Myer and Best to present a list of inmate grievances. More than 5,000 Tule Lake inmates gathered outside the administrative area in a peaceful show of support for the negotiating committee. Best refused to respond to the list of inmate grievances and tensions ran high on the evening of November 4. That night, a group of inmates saw trucks preparing to leave the camp, and suspected that food was being taken from the camp's warehouse to strikebreakers at nearby Tule Lake isolation center. Groups began to gather, and Best reacted by calling in the army. A handful of inmates were picked up by WRA internal security and savagely beaten before being turned over to the military police and imprisoned in the "bullpen" area of the hastily assembled stockade . [2] The next morning, when inmates prepared to go to work, they were tear gassed and greeted with a show of military force that included tanks and jeeps mounted with guns. The mass turnout frightened WRA employees who demanded that a barbed-wire fence be built to separate themselves from the Nikkei inmates. Newspaper reporters spun sensationalized tales of an armed insurrection and riots at Tule Lake.

Tule Lake became an armed camp with a prisoner curfew, barrack-to-barrack searches, and a near complete cessation of normal daily activities. Martial law was declared on November 14, leading to months of repression and hardship. Military police invaded private quarters looking for contraband and conducted a dragnet search of the entire camp to find the Daihyo Sha Kai leaders who were hidden by sympathizers. These leaders eventually turned themselves in to reduce the hardship inflicted on Japanese Americans by the army. They and over 200 Nikkei men were imprisoned in the primitive and overcrowded army stockade, some for as long as nine months, without hearing or trial. Among the "crimes" the army listed to justify imprisonment in the stockade: "general troublemaker," "too well educated for his own good," and "definitely a leader of the wrong kind." [3]

The period of martial law was a time of suffering and repression, with a curfew and an end to many activities. Only those in crucial service areas went to work; others remained idle with no income for months. There were shortages of milk, food, hot water and fuel to heat the barracks. The repression and prolonged hardship fostered widespread hostility toward the occupying army and the WRA and any person or group that cooperated with them and radicalized many of the unjustly imprisoned inmates.

Military control of Tule Lake ended January 15, 1944, but the experience of martial law led to a loss of faith in America, and Tule Lake inmates wondered what future they had in a country that showed little regard toward them. Within days of martial law ending, in what seemed like a perverse test of how much government hypocrisy would be endured, young men began receiving draft notices to serve in the army. Twenty-seven refused to leave Tule Lake to report for their physicals, and were put on trial for draft evasion. The U.S. District judge, Louis Goodman, in the only affirmation of WWII's Nisei draft resisters, dismissed the case, writing, "It is shocking to the conscience that an American citizen be confined on the ground of disloyalty, and then while so under duress and restraint, be compelled to serve in the armed forces, or be prosecuted for not yielding to such compulsion." [4] The draft resisters were freed to return to their families in the Tule Lake concentration camp.

In this distorted prison environment, imagining a future in America seemed pointless, and young men and women devoted themselves to preparing for a new life in Japan, attending Japanese language schools and learning about Japanese history and culture. Faced with emasculating criticisms of cowardice for refusal to serve in the army of the nation that imprisoned them, young men were swept up in a growing counter-narrative of pro-Japan zeal, a radical response to being labeled as disloyal and lacking courage. By the latter part of 1944, calisthenic drills that resembled militaristic marches became a conspicuous early morning activity. Many former Tule Lake inmates remembered their annoyance at being awakened by the sound of blaring bugles and chants of "washoi washoi," while others recalled the early morning runs and camaraderie as self-esteem building. One writer expressed his feelings about the growing pro-Japan fervor: "I did not feel that I had to subordinate myself, feel inferior or show deference to the whites... I felt proud to be Japanese." [5]

Turning American Citizens into Enemy Aliens

Seizing on reports of pro-Japan activity and unrest at Tule Lake, nativist and "anti-Oriental" groups promoted legislation that would strip citizenship from American-born Japanese. Their efforts culminated in passage of a denationalization bill, authored by Attorney General Francis Biddle that became law July 1, 1944. The law paved the way for disaffected American-born Kibei and Nisei to voluntarily reject their U.S. citizenship and become "enemy aliens." Once stripped of their citizenship, the Department of Justice could treat them as foreigners, intern them as prisoners of war and purge them from U.S. soil.

Initially, fewer than two dozen Tule Lake inmates applied to renounce their U.S. citizenship. However, on December 17, 1944, it was announced that incarceration would end and the camps would close within a year. The announcement caused collective shock in Tule Lake. Inmates were swept up in panic, consumed by anger, confusion and anxiety over thoughts they would be sent into hostile white communities with the war against Japan still going on. Tule Lake was in chaos, with inmates trying to figure out the best course of action to protect themselves and their families.

When army personnel began asking inmates if they planned to renounce and remain in Tule Lake, the message was clear; renunciation would allow a family to remain safe in Tule Lake until the war was over. [6] In the next several weeks, thousands of Japanese Americans in Tule Lake gave up their seemingly worthless citizenship. Some rejected their U.S. citizenship to express anger at America's injustice; others did so out of worry their families would be separated if the Issei were deported. Many renounced so they could remain at Tule Lake until the war ended, blaming coercion by pro-Japan bullies, who, like agents provocateurs, goaded others to renounce but did not do so themselves. [7] Within a few months, however, it became clear to the majority of those in Tule Lake who renounced that rejection of their American citizenship was a tragic mistake. Attempts to reverse their renunciations received little cooperation from the Justice Department.

Wayne Collins , the San Francisco civil liberties attorney who was instrumental in closing down Tule Lake's infamous military stockade, managed to derail the Department of Justice plans for mass deportations. On November 13, 1945, only two days before a ship filled with both willing and unwilling Japanese Americans departed for Japan, Collins obtained a court order that forbade their deportation until the matter could be heard before a judge. Collins charged that the renunciation program was a fraud, the result of duress caused by the mass incarceration and the pressure-cooker environment of Tule Lake.

Stopped from implementing a mass deportation plan, and not wishing to spend millions of dollars to keep renunciants imprisoned while awaiting trials, the Department of Justice arranged administrative hearings to cull the renunciants. Those who did not request a hearing were given deportation orders; those with hearings were expected to explain why they should not be deported. In February 1946, a contingent of 4,406 Tule Lake inmates voluntarily left for Japan, including 1,116 renunciants, 1,523 aliens and 1,767 U.S. citizens, the latter consisting mostly of children and adolescents. Of the remaining 3,186 Nisei and Kibei seeking hearings, 2,737 were released from camp, but without their citizenship. Stripped of their birthright, they became "native American aliens."

Tule Lake remained open for DOJ administrative hearings and was the last of the WRA camps to close. On March 19, 1946, the remaining 406 renunciants and their 43 family members were put on a train and shipped to the Department of Justice family internment camp in Crystal City , Texas.

The lawsuit that Collins initiated November 1945 wound through the courts, taking fourteen years to restore American citizenship to 4,978 stateless Nisei and Kibei. On March 6, 1968, 23 years after he stopped the wholesale expulsion of Japanese Americans, Collins concluded his formidable and extraordinary efforts on behalf of the renunciants.

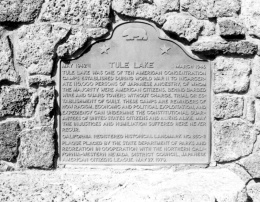

Preserving Tule Lake

Efforts to recognize the Tule Lake site were begun in the mid-1970s, culminating in 1979 with the placement of California State Historic Site marker #850B. The basalt and concrete marker, designed by Sacramento architect Alan Oshima, was placed along State Highway #139, and is a companion to State Historic site marker #850, placed at Manzanar. The Sacramento JACL Chapter and the Northern California District of the JACL raised funds for the marker project.

In 2000, the Tule Lake Committee, based in Northern California, began meeting with state and federal agencies and preservation groups to advocate for and raise funds to preserve the Tule Lake site. An all-volunteer organization, the Tule Lake Committee, Inc. plans a bi-annual, multi-day pilgrimage to remember and honor those incarcerated at the Tule Lake concentration camp and segregation center.

Tule Lake was recognized as the only maximum-security segregation center among the ten WRA concentration camps in July 2006, when a 33-acre portion of the site was designated as the Tule Lake Segregation Center National Historic Landmark, the highest recognition our nation grants to a historic site. The NHL area is on public land and includes the infamous army stockade area and the iconic concrete jail. In December 2008, the NHL portion of the Tule Lake concentration camp site and the nearby CCC camp known as Tule Lake isolation center were designated as the Tule Lake Unit of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument. The future of this national park site will be determined through a comprehensive NPS planning process to be undertaken over the next several years.

For More Information

Akashi, Motomu. Betrayed Trust: The Story of a Deported Issei and His American-Born Family During WWII . Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2004.

Azuma, Eiichiro. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America . New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

The Cats of Mirikitani . Video. Directed by Linda Hattendorf. 74 min. Lucid Dreaming, 2006.

Collins, Donald E. Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans during World War II . Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Drinnon, Richard. Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

From a Silk Cocoon . Video. Produced by Satsuki Ina. 90 min. 2005.

Ichioka, Yuji, ed. Views From Within: The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study . Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center, University of California at Los Angeles, 1989.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment During World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Kashiwagi, Hiroshi. Shoe Box Plays . San Mateo, CA: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2008.

———. Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings . San Mateo, CA: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2003.

Kumei, Teruko. "Skeleton in the Closet: The Japanese American Hokoku Seinen-dan and Their 'Disloyal' Activities at the Tule Lake Segregation Center during World War II." Japanese Journal of American Studies 7 (1996): 67–102.

A Meeting At Tule Lake . Video. Produced and directed by Scott Tsuchitani. 33 min. 1994.

Muller, Eric. Free to Die For Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Nakagawa, Martha. "Renunciants: Bill Nishimura and Tad Yamakido." Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005): 137–59.

National Park Service, Tule Lake Unit. http://www.nps.gov/tule .

Ross, John, and Reiko Ross. Second Kinenhi: Reflections on Tule Lake . San Francisco: Tule Lake Committee, 2000.

Takei, Barbara. "Legalizing Detention: Segregated Japanese Americans and the Justice Department's Renunciation Program." Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005): 75–105. https://archive.org/details/questionofloyalt00shaw

Takei, Barbara, and Judy Tachibana. Tule Lake Revisited, Second Edition . San Francisco: Tule Lake Committee, 2012.

Takita-Ishii, Sachiko. "Tokio Yamane: A Renunciant's Story." Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005): 161–85.

Thomas, Dorothy Swaine, and Richard S. Nishimoto. The Spoilage: Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946.

Tule Lake Committee. http://www.tulelake.org .

Wax, Rosalie. Doing Fieldwork: Warnings and Advice . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps New York: William Morrow and Co., 1976.

Footnotes

- ↑ Stan Turner, The Years of Harvest: A History of the Tule Lake Basin (Eugene, OR: 49th Avenue Press, 1987), 264–265; Mark Clark, "'The Deadly Enemies That They Are': Local Reaction to the Tule Lake Internment Camp," Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005): 46–47.

- ↑ Richard Drinnon, Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 137–44.

- ↑ Col. Verne Austin Papers, UCLA Archives, collection 2010, box 43, folder 3.

- ↑ Eric Muller, Free to Die For Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 143.

- ↑ Motomu Akashi, Betrayed Trust: The Story of a Deported Issei and His American-Born Family During WWII (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2004), 199.

- ↑ Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard S. Nishimoto, The Spoilage: Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946), 338.

- ↑ Barbara Takei, "Legalizing Detention: Segregated Japanese Americans and the Justice Department's Renunciation Program," Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005), 88–92.

Last updated Dec. 21, 2023, 1:58 a.m..

Media

Media